|

The

Catacombs of Kom el Shoqafa

|

Tradition has it that on Friday, September 28th,

1900, in Alexandria, Egypt, a donkey, hauling a cart full of

stone, made a misstep and disappeared into a hole in the ground.

If that story is accurate, this beast of burden made one of

the most astounding discoveries in archeological history: A

set of rock-cut tombs with features unlike that of any other

catacomb in the ancient world.

We actually don't know if the donkey story is

true or not, but records do show that the shaft was reported

to authorities by a man named Monsieur Es-Sayed Aly Gibarah.

Following the rules about such finds in those days, he sent

a message to the local museum saying, "While quarrying for stone,

I broke open the vault of a subterranean tomb. Come see it,

take the antiquities if there are any, and authorize me to get

on with my work without delay." The curator, tired of being

called out to sites and finding nothing of importance, didn't

go himself, but sensing the man's impatience to get on with

the work, sent two of his assistants home early, telling them

to check out the find on the way. What they found brought the

curator out the next day and he spent much of the rest of his

life documenting this unique discovery.

|

Seven

Quick Facts

|

| Maximum

depth below ground: 100 feet (30m) |

| Rediscovered:

September 28th, 1900 |

| Made

by: Cutting into the natural underground rock. |

| Constructed:

2nd Century AD |

| Function:

Tombs with ceremonial feasting hall. |

| Style:

Mixture with Egyptian, Greek and Roman elements. |

| Other:

Supposedly discovered when a donkey fell through a hole

in the ground. |

Paris

of Antiquity

Archeologists believe that the Catacomb of Kom

el Shoqafa was started in the 2nd century A.D. and was used

to intern the dead for the next 200 years. This was a period

in the history of the city of Alexandria when there was a great

mixing of different cultures. Of course, there was the ancient

history of the great Egyptian kingdoms which went back thousands

of years. Also in 332 B.C. Alexander the Great had conquered

the land, established the city of Alexandria, and started a

dynasty of Greek rulers who brought their own culture to the

metropolis. Finally, in 31 B.C. the Romans took control of the

city and added their traditions.

This made Alexandria, which was then the capital

of Egypt, into what some have called "The Paris of antiquity."

People combined the elements of these three great cultures together

in surprising ways. Though much of this has now disappeared

from modern Alexandria, deep in the Kom el Shoqafa catacombs,

the intellectual blend of those times is still apparent.

These catacombs are not the only ones that were

constructed in ancient Alexandria. Such structures were part

of a Necropolis (or "city of the dead") that was probably built

(according to Egyptian tradition) on the western edge of the

town. Most of the rest of the Necropolis, however, was probably

destroyed over the centuries by earthquakes or new construction.

Archeologists speculate that Kom el Shoqafa was started as a

tomb for a single, wealthy family, but was expanded into a larger

burial site for unknown reasons. Most likely the facility was

eventually run by a corporation which was supported by members

who paid regular dues.

|

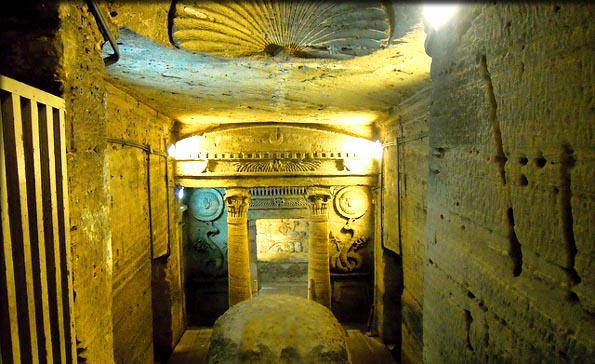

The

doorway into the "temple."

|

The name of the site, Kom el Shoqafa, means

"Mound of Shards." The name comes from heaps of broken pottery

in the area. Archeologists believe that these were left in ancient

times by relatives who would visit the tomb bringing food and

drink with them. The visitors, not wanting to bring vessels

that had been used at a gravesite back to their homes, would

shatter them and leave them behind in piles.

Layout

of Tomb

On the surface above the catacombs in ancient

times was probably a large funerary chapel. From the remains

of this edifice an 18-foot (6m) wide, round shaft descends into

the underground structure. Running around the outside of the

shaft but separated by a wall is a spiral staircase with windows

into the shaft that allow light coming from the surface to illuminate

the stairs. It is likely that the shaft also enabled the bodies

of the deceased to be lowered down to the deeper levels through

a rope and pulley system rather than being carried down the

steps.

At the junction of the uppermost underground level

and the stairs there are seats caved into the stone where visitors

could rest. A short passage from here leads to the rotunda room,

which overlooks a round shaft that continues down to the lower

levels. To the left of the rotunda room is a funeral banquet

hall known as the "Triclinium." It is here that relatives would

participate in annual, ceremonial feasts to honor the dead.

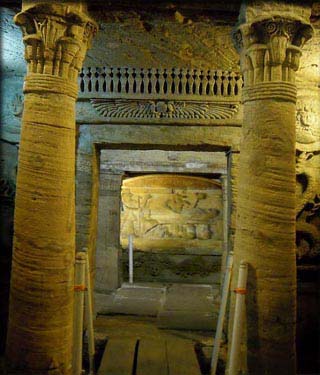

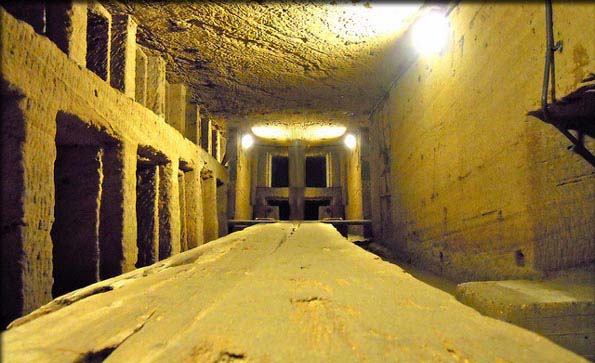

Steps from this upper level continue down to the

middle level which is the main part of the tomb. This section

is laid out much like a Greek temple. At the bottom of the steps

is the pronaos, or porch, of the temple set between two

columns. This area was originally designed to be surrounded

by a single u-shaped corridor that contained the burial niches.

As more space was needed, however, additional rooms and halls

were added, turning the complex into a labyrinth.

Below the middle level, at the lowest level, additional

internment niches are located, but that area is flooded and

inaccessible to visitors.

Blend

of Styles

|

The

Agathodaimon wearing an Egyptian double crown and carrying

a Roman kerkeion (right) and a Greek thyrus (left).

|

The main tomb at the middle level is covered with

the sculpture and art that makes this catacomb unique. For example,

in the room behind the temple pronaos are statues of a man and

woman (perhaps representing the original occupants of the tomb).

Both of the statues' bodies have been carved into the stiff

hieratic poses found in ancient Egyptian art. The man's head,

however, has been chiseled into the lifelike style favored by

the Greeks. In the same way the woman's head has been carved

with a Roman hairstyle.

On either side of the doorway of the temple's

facade there are two serpents carved in relief. These are meant

to guard the tomb. They represent a Greek Agathodaimon

(which is a good spirit). The Greek serpents are wearing traditional

Egyptian double crowns, however, and in their coils they carry

both a kerkeion (a winged staff) which is a Roman insignia and

a Greek thyrus (a staff topped by a pinecone). Above the serpents'

head are Greek shields carrying the image of the legendary Greek

monster Medusa (whose use here is meant to ward off unfriendly

intruders).

It is this mix of art and culture - Egyptain,

Greek and Roman - that is not found in any other catacomb in

the ancient world that makes Kom el Shoqafa special.

From the rotunda it is possible to enter a separate

set of tombs through a hole in the wall. This section, known

as the Hall of Caracalla contains the bones of horses and men.

The name comes from an incident in 215 AD when the Emperor Caracalla,

massacred a group of young Christians. While we do know that

such a massacre did occur, there is no actual evidence that

the remains in the hall are related to that incident. Why the

men and horses are buried together in the hall continues to

be a mystery.

The fact that this set of tombs serviced several

different cultures can also be seen by the modes of internment

themselves. The tomb has many sarcophagi for the placement of

mummies in the Egyptian tradition, but also numerous niches

meant to hold the remains of those who chose to be cremated

in the Greek and Roman style. As one writer put it, the catacomb

is "visible evidence of an age when three cultures, three arts,

and three religions were superimposed upon Egyptian soil."

Copyright

2012 Lee Krystek. All Rights Reserved.

All photos

by Elizabeth Skene licensed under Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0

Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0)