|

The

Great Eastern

|

It was

the largest ship of its era. So massive it was renamed the Leviathan

for its 1858 launch. Though the vessel was a failure at the

Far East passenger trade that it was designed for, it later

achieved great success as it laid the first fully effective

underwater Atlantic cable while operating under its proper name,

The Great Eastern.

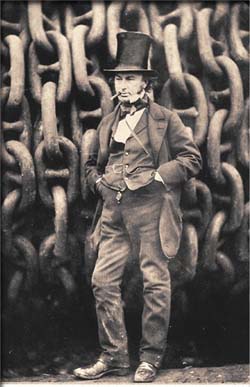

By 1852

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was already a well-known British engineer

with a list of successful projects to his credit: Several bridges

with innovative features, the building of Britain's new Great

Western Railway, and also the construction of two ships: the

Great Western and the Great Britain. These last two projects,

both passenger ships, had been undertaken to take advantage

of the growing trade between Britain and North America. With

their success, Brunel wondered if there might be a need for

a passenger ship designed to handle traffic to the Far East,

visiting ports in China and Australia.

Such

a ship, he reasoned, would need to be huge. Large enough that

could travel around the world without fueling. Such a big ship

would also benefit from the so called "economy of scale." For

example, it might not need a much larger crew than a smaller

ship, but it would be able to carry many more passengers and

cargo, which would translate into more profit.

|

Seven

Quick Facts

|

|

-Length:

692

feet (211m)

|

|

-Beam:

83

feet (25m)

|

|

-Design:

Iron hull powered by sails, steam paddles and steam propeller.

|

|

-Construction

dates: 1854 - 1859

|

|

-Designer:

Isambard

Kingdom Brunel

|

|

-Function:

Passenger ship later converted to laying submerged

telegraph cable.

|

|

-Other:

Designed for 4,000 passengers and 400 crew.

|

With

this in mind, Brunel sketched out a picture of such a ship in

his notebook with the caption "Say 600 feet x 65 feet x 30 feet."

A ship

of such dimensions not be easy to build, however. It would be,

by volume, more than four times as large as any ship currently

in service at the time. Still, Brunel liked a challenge and

he gave the design to John Scott Russell, a navel engineer he

respected, who had already constructed several ships designed

by Brunel.

Scott

calculated such a ship would have a displacement of about 20,000

tons and would need at least 8,500 horsepower to achieve a speed

of 14 knots (about 16 mph). One novel feature that the ship

was designed with was multiple means of propulsion. It would

have masts and sails to take advantage of the wind and both

side paddles wheels and a screw (what most people today would

probably refer to as a propeller) which would be powered by

steam engines.

Eastern

Steam Navigation

Brunel

and Scott approached the Eastern Steam Navigation Company about

their idea. Eastern Steam wanted to get into the Far East trade

but had lost an important contract from British General Post

Office to transport mail to the East Asia. The only way they

might be able to make a profit without it was by utilizing such

an efficient ship as Brunel was proposing.

In July

of 1852, the company reviewed the proposal and decided to build

the ship, putting Brunel in charge as the chief engineer. Brunel

then started looking for vendors to build the major components

of his design: the hull, paddle engines and screw engines.

|

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

|

Brunel's

estimate for the cost of building the ship came to £500,000.

Scott's company, however, put in a bid of only £377,200 to successfully

win the contract. Brunel trusted Scott's engineering competency

and did not question the bid. Scott, however, was a better engineer

than businessman and his low figure was to cause serious problems

with finishing the ship's construction.

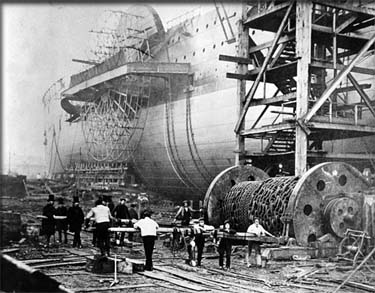

Construction

Assembly

began in the spring of 1854 on a leased plot of land next to

Scott's shipyard in Millwall, London. Nothing as big as this

ship had ever been built before and the problems of how to erect

it were significant. No dry dock was nearly big enough to hold

it. It was finally decided to build it lengthwise next to the

river with the idea of sliding sideways into the water when

the time came.

Brunel's

innovative design included a double, iron-skinned hull, so that

if the outer hull got a hole in it, the inner hull would still

keep the water out. Such a design was unheard of at the time,

but now is required of all modern ships.

Everything

about the ship was big. Its crew complement would be 400 and

it could carry 4,000 passengers (Twice that of other ships operating

in the same era). The paddle wheels on the sides of the ship

were immense - 54 feet (17m) in diameter. The propeller was

also enormous, being 24 feet across (7.3m). The vessel also

had a record five smoke funnels for the engines and six masts

for sails.

The

work progressed, but by the beginning of 1856 it became clear

that Scott's company was in financial trouble. Eventually his

bankers agreed to turn the ship over to Eastern Navigation and

lease his yard to them so that they could complete the ship

themselves. A year of work went by and under pressure to get

the ship out of the yard and into the water, Brunel reluctantly

agreed to try and launch the vessel on November 3rd of 1857.

The

Eastern Navigation Company sold 3,000 tickets to people who

wanted to see this enormous ship slide into the river that day.

They were disappointed. The steam winches that were supposed

to drag the ship into the water were not up to the task of moving

the vessel which was 692 feet (211m) long and 83 feet (25m)

wide. Brunel tried again several more times before successfully

launching her on January 31st of 1858.

By then

the cost of building the ship and launching her had brought

Eastern Navigation to the brink of bankruptcy. In order to finish

the ship's interior it was decided to create a new company,

the Great Ship Company, which bought the ship from Eastern Navigation.

Ironically, despite earlier problems, Scott Russell's company

was allowed to bid for and win this part of the contract, too.

Work started in January of 1859 and finished in August.

|

The

Great Eastern under construction in 1858.

|

Maiden

Voyage Explosion

The

maiden voyage of the vessel, which started on September 6th

of 1859, was marked by an unfortunate incident. As the Great

Eastern moved into the English Channel, a huge explosion rocked

the vessel and one of the funnels was blown off. Six men were

killed and nearly as many were seriously injured. The explosion

was caused when feed water pipes for the boilers which ran around

the funnel to cool it and pre-heat the water had been accidentally

closed off. As the funnel warmed the water in the pipes eventually

it turned to steam, expanded, and the pipes, not designed to

hold back that kind of pressure, gave way.

The

ship was not in danger of sinking, however, and the voyage continued

to Weymouth, where repairs were made.

Burnel,

for health reasons, was not aboard the ship when it made its

maiden voyage. A heavy smoker, he suffered a stroke in 1859

and died just before the ship made its first trans-Atlantic

trip.

Though

the ship was designed for voyages to the Far East, it turned

out that there was never the amount of traffic going in that

direction to support its operation. Instead, from 1860 through

1863, she was put into trans-atlantic service between England

and the United States. However, the competition was so stiff

the Great Ship Company never became profitable and they decided

to sell the ship in 1864.

Several

attempts were made to sell the ship before it was bought by

the newly-formed Great Eastern Steamship Company. Instead of

putting the ship back into passenger service, however, the owners

had another idea. They chartered it to Telegraph Construction

and Maintenance Company and retro-fitted it to lay undersea

telegraph cables. It was in this new role that the Great Eastern

would have its most outstanding successes.

Laying

the Atlantic Cable

In 1837

electrical telegraphs had been developed independently in both

Europe and in North America. Within two decades both continents

were crisscrossed by wires connecting almost all major cities,

allowing same day communications between almost any urban location

on those continents. Communications between Europe and North

America, however, were still limited by the length of time it

took a ship carrying a message to cross the seas: At least 10

days.

|

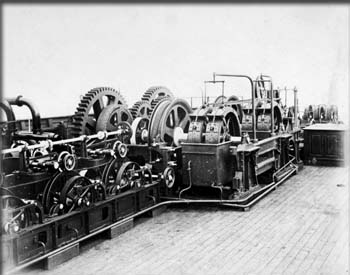

Some

of the cable laying machinary on the deck.

|

The

first attempt to lay a telegraph cable across the Atlantic was

completed in 1858. Unfortunately because of poor quality materials,

the cable stopped functioning after three weeks. However, this

did prove that such a plan was viable and in a new effort, using

the refitted Great Eastern was started.

To this

end one of the funnels was removed along with some boilers.

Many of the staterooms were also gutted and large open topped

tanks, designed to hold 2,300 nautical miles of coiled cable,

were installed.

In July

of 1865, Great Eastern left Valentia Island, Ireland, headed

for Canada. All went well for 1,200 miles, when suddenly the

cable snapped and the end dropped into the sea. Many attempts

were made to use grappling hooks to capture it again, but they

all failed.

An attempt

to lay another cable was made in 1866. This time the Great Eastern

set the cable without incident and on July 27th, 1866, arrived

at the tiny fishing village in Newfoundland called Heart's Content.

The ship managed to lay an average of 120 miles of cable a day.

Immediately

after laying the new cable the ship went back to sea and made

another attempt at recovering the cable lost in 1865. This time

the crew was successful in recovering it. On board the Great

Eastern, the old cable was spliced with a new one. Then the

ship headed back to Hearts Content laying the 2nd cable. By

September 8th a second cable was finished, ensuring that from

that day forward the North American and European continents

would be linked by telegraph.

The

ship continued laying submerged cables until 1870. Attempts

after that were made to put her back into passenger service,

but this failed. For a few years she was used as a showboat,

a floating concert hall and gymnasium, but eventually in 1888

she was scrapped. A sad end for a noble ship with a design that

was far ahead of its time.

|

The

Great Eastern beached prior to being scrapped.

|

Copyright

Lee Krystek 2016. All Rights Reserved.