|

Paricutin:

The Volcano in a Cornfield

|

On February

20, 1943, Dionisio Pulido was working in his cornfield just

outside the Tarascan Indian village of Paricutin, Mexico. He

and his family had spent the day getting ready for the spring

sowing by clearing the field of shrubbery, putting it in piles

and burning it. At about four in the afternoon, Pulido left

his wife and moved to a different field so that he could set

fire to a new pile. When he arrived he noticed something strange:

on top of a small hill in the field a huge crack, over six feet

wide and 150 feet (47m) long, had appeared in the earth. At

first Pulido wasn't concerned, the crack only looked like it

was about a foot deep. As he was lighting the pile of branches,

however, the sound of thunder rumbled across the field and the

ground began to shake. Pulido turned to look back towards the

crack and saw that the ground there had swelled up over six

feet in height and fine gray ashes were pouring out of the hole.

"Immediately more smoke began to rise with a hiss or whistle,

loud and continuous; and there was a smell of sulfur," Pulido

later told witnesses.

|

Seven

Quick Facts

|

| Height:

1,353 foot (424m) above the valley. 9,186 feet ( 2,800m)

above sea level. |

| Area:

Lava field covers 10 square miles (25 square km). |

| Eruption:

1943 to 1952. |

| Type

of Volcano: A scoria (or cinder) cone. |

| Discovered:

Farmer Dionisio Pulido saw it emerge out of his cornfield

on February 20th , 1943, at around 4 PM. |

| Location:

Near the destroyed town of Paricutin in the state of

Michoacán, Mexico. |

| Other:

The youngest volcano in the Western Hemisphere. |

Pulido

became terrified by these events and tried to find his wife

and sons, but couldn't. He tried to rescue his team of oxen,

but they had disappeared also. Despairing that he would never

see any of them again, he jumped on his horse and rode to town.

There he was happy to find his family and friends waiting for

him. "They were afraid that I was dead and that they would never

see me again," said Pulido.

What

had appeared in Pulido's cornfield was a new volcano. The incident

at Paricutin would be the first time scientists would be able

to observe a volcano from birth through extinction. What they

would learn through these events would help them understand

the powerful forces deep in the earth that shape the surface

of our planet.

Trans-Mexican

Volcanic Belt

The

town of Paricutin was located in the heart of the Trans-Mexican

Volcanic Belt, an area running 600 miles (900 km) east to west

across central-southern Mexico. The belt includes the Sierra

Nevada mountain range (which is an extinct set of volcanoes)

along with thousands of smaller cinder cones and volcanic vents.

Volcanic activity over millions of years has created a high

plateau of rock deposits 6,000 feet (1.8km) deep. The soil,

because of its volcanic origin, contains a wide variety of common

elements which are easy for plants to absorb. This makes the

land very fertile. The soil, combined with moist winds from

the Pacific Ocean, makes the belt the most productive farmland

in Mexico.

|

The

volcano as it appeared in 1943 during the eruption.

|

Even

though the belt had a long history of volcanic activity, the

residents of Paricutin thought they had been hearing the sound

of normal thunder in the weeks that preceded the eruption, though

they were puzzled by the lack of storm clouds in the sky. What

was producing the sound, however, was the movement of magma

deep inside the earth. Soon, however, residents also began feeling

tremors in the ground, hinting of what was to come.

After

its startling appearance, the volcano grew rapidly. That first

evening Celedonio Gutierrez, who witnessed the eruption from

the town remembered, "…when night began to fall, we heard noises

like the surge of the sea, and red flames of fire rose into

the darkened sky, some rising 800 meters or more into the air,

that burst like golden marigolds, and a rain like artificial

fire fell to the ground."

The

volcano grew by ejecting both lapilli-sized fragments, which

range from the diameter of a pea to that of a walnut, along

with larger "bomb" fragments. The bombs are often still molten

when they are thrown from the volcano and produce bright parabolic

streaks in the sky as they fall to the ground. Because they

are still soft while flying through the air, the bombs form

into a streamlined, aerodynamic shape.

As

the bombs and lapilli build up around the base of the eruption,

they form a steep cone shape often referred to as a scoria,

or cinder cone. In a little more than 24 hours the cone of the

Paricutin volcano had grown to over 165 feet (50m). Within six

more days it had doubled that height.

World

Attention

In

March, about a month after the eruption started, William F.

Foshag, a curator of minerals at the U.S. National Museum, arrived.

Together with his Mexican counterpart, Dr. Jenaro González-Reyna,

Foshag would spend the next several years documenting the life

cycle of the volcano. Froshag was responsible for gathering

many of the samples and photographs from Paricutin that are

still used by scientists today while doing volcanic research.

|

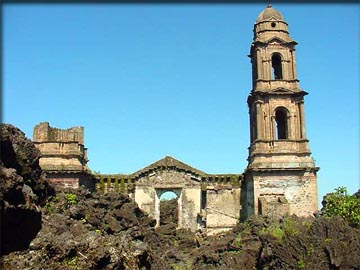

The

remains of the San Juan Parangaricutiro Church which still

rise above the rugged lava feild. (Photo

credit: Sparksmex)

|

The

sudden appearance of a new volcano caught the attention of the

world. Newspaper and magazine reporters rushed to the area.

Life Magazine featured a picture of Foshag with the volcano

in the background. Pilots of airliners would point out the cone

to fascinated passengers as they flew by it. Hollywood even

got into the act by shooting a film, Captain from Castile,

in the region and using the volcano as a dramatic backdrop.

While

the residents of Paricutin might have been happy about the work

they got as extras in the movie, it was hardly compensation

for the damage the volcano did. In June of 1943 lava started

flowing toward the village which had to be evacuated. A few

months later the lava also rolled over the nearby town of San

Juan. Eventually all that was left of the settlements was the

church towers which rose above a sea of lava. A frozen, rugged

sea that by the time it has stopped flowing covered 10 square

miles.

Volcano

Types

Volcanoes

come in three basic types (though sometimes scientists include

supervolcanoes as a fourth

type). Shield volcanoes are broad, dome-like structures

that can grow to over 60 miles (100km) wide. Instead of violent,

explosive eruptions they are characterized by steady lava fountains

and flows that broaden the size of the volcano. The volcanoes

of Hawaii fall into this category.

|

Paricutin

Today

Today

the volcano is silent. Visitors can experience Paricutin

by traveling to the nearby town of Angahuan that survived

the eruption. This location is known as the "Balcony of

the Paricutin" and from its location on top of a mountain

both the extinct volcano and its surrounding lava fields

can be seen along with the ruins of the church of San

Juan. The bell tower of the church still stands like a

lonely sentinel above the frozen lava part of one of the

wonders of the natural world.

|

Stratovolcanoes

are the most violent and dangerous of volcanoes. Their slopes

rise slowly at first and then become very steep with a narrow

vent at the top. Stratovolcanoes often have explosive eruptions,

and then go dormant for decades or even centuries. Mt. St. Helens,

in the United States Pacific Northwest, is a Stratovolcano.

The

final type of volcano is one like Paricutin, a scoria cone.

This type of volcano can appear suddenly and build a large conic-shaped

mountain with steep slopes. They often erupt for less than a

decade, then go dormant and never erupt again. The type of eruptions

from such cones are known as Strombolian eruptions because

the lava flows out of a single vent that resembles those at

the Stromboli volcano in Italy.

End

of the Volcano

Paricutin

was very active in its first year, growing to four-fifths of

its final 1,353 foot (424m) height. During the peak of its activity

that year, ashes from the volcano drifted as far as 200 miles

to the east and fell on Mexico City. With each following year,

however, the volcano became less active until, after a final

spectacular spasm, it finally went dormant in 1952. By then

the damage had been done, however. In addition to the lava fields,

there were also 20 square miles of volcanic sand deposited around

Paricutin and almost all vegetation had been destroyed within

a few miles of the crater. Hundreds of people had been resettled

to other locations and had to find new livelihoods.

Before

leaving his home for the final time Pulido put a sign on his

land. It read "This volcano is owned and operated by Dionisio

Pulido." Paricutin might have taken his cornfield, but the farmer

still retained his sense of humor.

|

The

quiet volcano as it appears today. (Licensed

under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license,

photo by Karla Yannín Alcázar Quintero)

|

Copyright

Lee Krystek 2012. All Rights Reserved.