|

Building

the Trans-Continental Railroad |

As the middle of the 19th century loomed, there

was no good, efficient way to cross North America from coast-to-coast.

An overland trip using horses and wagons across the Great Plains

was long, arduous and dangerous. Going by ship meant a six-month

trip around South American's Cape Horn, risking storms and ship

wrecks. A combination of the two, a ship to the Isthmus of Panama

with a land crossing there of the jungle and another voyage

to San Francisco, was fraught with the possibility of contracting

malaria or yellow fever. What was needed was to build a railroad

across America, but that seemed an impossibility.

While building the 1,907 miles (3,069 km) of track

that would be needed was not a small job; the biggest obstacle

to such a project was the Sierra Nevada mountain range. This

formable set of mountains runs 400 miles north and south and

70 wide east and west along the eastern edge of California.

Before the state of Alaska was added to the union, it was the

highest and longest mountain range in the United States.

It wasn't the size or even the height of the mountains

that made it such a difficult problem for the railroad, but

the steepness. A railroad engine pulling cars can only climb

a grade of 2% under normal conditions (a rise of two feet for

every hundred foot of track). Because the Sierra Nevada was

so steep and its valleys so narrow, it seemed impossible that

one might build a gently-sloping track through them. Making

any attempt at doing this even more difficult was the weather

coming off of the Pacific Ocean that deposited extreme snow

in the range, sometimes as deep as 50 feet.

Theodore Judah

|

Seven

Quick Facts

|

| -Authorization:

Lincoln signed Pacific Railway Act into law on July 1st,

1861. |

| -Length:

1,907-miles (3,069 km) of track from Omaha to Sacramento. |

| -Start:

January 8, 1863, in Sacramento. |

| -Completion:

May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit, Utah. |

| -Most

track laid in a single day: 10 miles by the Central Pacific

Railroad on April 28, 1869. |

| -Cost:

$150 to travel from coast to coast after the railroads

completion. |

| -Other:

Parts of the railroad, especially through the Sierra

Nevada Mountains, are still in daily use today.

|

Despite these challenger one man thought it could

be done. His name was Theodore Judah. Judah was a young, ambitious

engineer that by the 1860's had already built California's first

railroad. Judah dreamed of linking the coasts with a ribbon

of steel and took 23 trips into the mountains to scout a path.

In 1862 he traveled east to the nation's capital in Washington,

D.C. to convince the government that such a project could succeed.

Judah met with members of Congress and President

Lincoln. Lincoln, in particular, saw the need, especially during

the Civil War, of uniting the country with a rail line. So in

1862 he signed the Pacific Railroad Act. This law authorized

two companies, one working from the east and the other working

from the west, to build a railway across the western United

States. To encourage this endeavor, the government would grant

$16,000 for each mile of track laid over flat ground. The money

increased as the terrain got steeper, topping out at $48,000

in the most difficult mountains. In addition. the railroad companies

would be granted a 400 foot right-of-way along the tracks (later

the government would double this). This land grant was also

a huge financial enticement as the property along the tracks

would be very valuable once the rails were laid and the line

was in service.

Central Pacific Railroad

Judah worked with four shopkeepers from Sacramento,

California, to form the Central Pacific Railroad Company in

1863. The group had difficulty in raising the necessary funds,

however, and Judah had disagreements with the partners as he

perceived they were using legally-questionable schemes to obtain

the cash needed. Unfortunately, during a trip to the East Coast

to find new backers, Judah contracted yellow fever in Panama.

Ironically he died within a few days of a danger his proposed

railroad would have banished.

Without his chief engineer, the superintendent

of the Central Pacific, Charles Crocker, had to forge on by

himself. Perhaps the biggest problem he faced was labor. There

wasn't enough men in the Sacramento area to build the railroad

and those he did hire were soon enticed away by the promise

of silver and gold in the nearby mines of Nevada. In desperation,

Crocker decided to hire Chinese laborers. The Chinese were shockingly

discriminated against in California at the time and at first

his foremen and engineers were skeptical of the Asians' abilities

to do heavy construction work. As the project progressed, however,

it became obvious that these immigrants would take on the most

difficult and dangerous jobs with tireless efforts. Eventually,

they were employed in large numbers.

To push the rail line through the Sierra Nevada

Mountains, a large number of bridges and tunnels were required.

This meant blasting away many tons of rock. For this, gun power

was used. Using a method imported from their native country,

the Chinese would weave giant baskets and attach them to ropes.

The baskets would be lowered down from the top of a cliff filled

with workers aboard who would chisel holes in the rock and fill

them with gun power. After lighting the fuses, they would be

pulled up to the top of the cliff before the detonation.

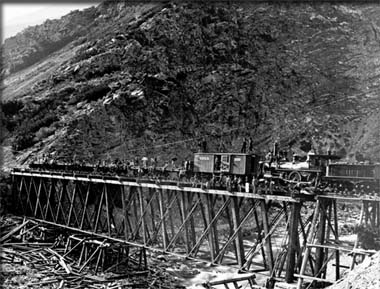

|

Building

the Devils Gate Bridge over Weber Canyon in 1869.

|

Use of the basket was a dangerous arrangement

as high winds would blow it about and a small mistake could

set the gun power off prematurely. This procedure became even

more dangerous when the railroad tried to speed construction

by using the newly-invented explosive, nitroglycerine. Nitro

was more powerful than gun power, but was unstable and could

easily be set off by a small shock. The Central Pacific tried

to use nitro during two different periods, both ending in disaster

and the death of many Chinese labors. In the final accident,

construction foreman James Strobridge lost an eye, bringing

experiments with the dangerous blasting oil to an end.

With the winter came massive snows and the associated

avalanches brought construction to a standstill. To protect

the tracks and crew, it was necessary to build wooden snow sheds

over the right-of-way. These sheds, which ran along where the

track had been cut into a steep hill, had sloped roofs designed

to allow snow coming down the hillside to slide right over the

tracks without covering or damaging them, and then into the

valleys below. By the time construction was, over 37 miles of

these wooden snow sheds had been built.

Union Pacific Railroad

Back East, Dr. Thomas Durant had been named the

leader of the Union Pacific Railway which would forge a path

from the existing tracks in the Mid-West towards the Pacific

coast. The two railways would be in competition to lay as much

track as possible. Since the federal goverment granted money

and land for each mile laid, each company had the incentive

to do as much construction as they could.

In 1866, after several changes in chief engineers,

Civil War veteran General Grenville Dodge was put in charge.

He settled on a route starting from the city of Omaha and running

up the Platte Valley. While initially the Union Pacific would

have it much easier as they were laying track through much flatter

land, eventually they would need to cross the Rocky Mountains,

a significant obstacle, but not nearly as difficult as the Sierra

Nevada Range the Central Pacific would have to conquer.

To allow work to move quickly, General John S.

Casement, who was in charge of construction, built several railroad

cars equipped as portable bunkhouses and a galley for his men.

In addition, temporary, "hell-on-wheels" towns, made mostly

of canvas tents, also followed the moving construction site.

To provide meat, a herd of cattle was kept close by and hunters

were employed to augment this food supply with buffalo meat

from wild American bison found in the area.

|

A

Central Pacific Chinese railroad crew working in the snow.

|

Much of the difficulty General Dodge and his team

encountered was not with construction challenges, but with the

native American tribes they encountered. Decades of encroachment

on Indian lands by the Europeans had made the tribes distrustful

of the white man. The Native Americans saw his "iron horse"

and its tracks as a further violation of their territory. They

were also concerned with the massive hunting of the bison as

these animals provided much of the Indian's sustenance. All

these factors caused some of the Native American tribes to take

violent action to prevent the railroad's progress.

While the main construction group working on the

rails numbered about a thousand, making them difficult to attack,

smaller survey and preparation teams working ahead were easy

targets. In August of 1867, a band of Cheyenne, looking for

revenge on white soldiers that had stolen from them, knocked

down a telegraph line along the tracks. When a team of six repair

men were sent out to investigate, they were attacked and scalped.

Only one survived by playing dead. While he watched, the band

also attacked an approaching freight train, killing both the

engineer and fireman.

After a number of these incidents, General Dodge

appealed to the government for help. General Sherman, the former

Civil War hero who had burned Atlanta, promised to protect the

railway workers by waging war on the Native Americans.

Another problem was that the towns along the Union

Pacific's route often became dens of gambling and violence as

workers let off steam from their difficult and dangerous jobs.

It is from these thse towns many of the legends of the vilolent

American West were formed. Julesburg, Nebraska, soon acquired

the reputation as "the wickedest town in America" where, according

to journalist Henry Stanley, "not a day passes but a dead body

is found somewhere in the vicinity." Gamblers, desperados, gun

slingers and prostitutes all called the city their home.

General Dodge, angered by the activity in Julesburg

and the fact that it was occurring on Union Pacific land, ordered

the town to be cleared out and John Casement, in charge of railroad

construction, took 200 railroad men armed with rifles into it.

In the end, 30 of the squatters were killed and Casement declared

proudly, "They all died with their boots."

The Final Spike

Eventually, the Union Pacific rail line crossed

the Rockies and the Central Pacific completed its Sierra Nevada

tracks. The question soon became, where would the two railways

meet? Because each company was earning government money for

each mile of track laid, there was little incentive to find

a logical meeting point. Teams grading and preparing the land

for the track actually passed by within sight of each other

heading opposite directions. As a source of pride, the railways

also attempted to outdo each other on the amount of track they

could lay in a single day. The Central Pacific took the record

by laying 10 miles on April 28, 1869.

The U.S. President, General Grant, had to threaten

to withhold funds from both competitors before they finally

decided on an agreeable mutual meeting point at Promontory Summit,

north of the Great Salt Lake in Utah.

The combined railway was officially opened on

May 10, 1869. Two highly-decorated engines, one from each railway,

were pulled up within a few feet of each other with trains behind

them filled with celebrating workers. In between the trains

at the final connection, there was a ceremonial driving of the

"Last Spike," made of gold with a silver hammer. After the ceremony,

the spike was removed and is now in the Cantor Arts Center at

Stanford University.

News of the achievement was sent around the world.

A telegram arrived for President Grant declaring, "The Last

Rail is Laid! The Last Spike is Driven! The Pacific Railroad

is Completed!"

Once the railway went into service, travel time

from coast-to-coast dropped from six months to just a week (By

1876, an express service was offered that would take a person

from New York City to San Francisco in only 83 hours). The cost

also dropped from around $1,000 to just $150, so people and

goods could move across the country quickly and cheaply. The

rail line transformed the settlement of the American West by

bringing western states and territories firmly and profitably

into the "Union." Just as President Lincoln had thought, the

ribbon of steel had united the nation.

Construction

of the Union Pacific reaches a lone pine designated

as the "1,000 Mile Tree," a thousand miles

from the start at Omaha.

|

Copyright

2016 Lee Krystek. All Rights Reserved.