pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

The Tower of BabelNow the whole earth had one language and few words. And as men migrated from the east, they found a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there. And they said to one another, "Come, let us make bricks, and burn them thoroughly." And they had brick for stone, and bitumen for mortar. Then they said, "Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth." And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which the sons of men had built. And the Lord said, "Behold, they are one people, and they have all one language; and this is only the beginning of what they will do; and nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. Come, let us go down, and there confuse their language, that they may not understand one another's speech." So the Lord scattered them abroad from there over the face of the earth, and they left off building the city. Therefore its name was called Babel, because there the Lord confused the language of all the earth; and from there the Lord scattered them abroad over the face of the earth. - Genesis 11. The story of the tower of Babel found in the Bible is familiar to many. Is there evidence that such a tower really existed? There are archaeological indications that it did, indeed. In the fertile Mesopotamian plain between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, in what is now modern Iraq, is a mound, or tell, of broken mud-brick buildings and debris. This is all that remains of the ancient famed city of Babylon. Babylon was one of a number of cities built by a succession of peoples that lived on the plain starting around 5,500 years ago. There developed a tradition in each city of building a temple in the shape of a stepped pyramid. These temples, or ziggurates, most likely honored a particular god. The people of Mesopotamia believed in many gods and often a city might have several ziggurates. Over time Babylon became the most influential city on the plain and its ziggurat, honoring the god Marduk, was built, destroyed and rebuilt until it was the tallest tower.

Constructing ziggurats on the Mesopotamian plain was not easy. The area lacks the stone deposits the Egyptians used effectively for their timeless monuments. The wood available is mostly palm, not the best for construction, so the people used what they had in abundance: mud and straw. The bulk of the towers were constructed of crude bricks made by mixing chopped straw with clay and pouring the results into molds. After the bricks were allowed to bake in the sun they were joined in construction by using bitumen, a slimey material imported from the Iranian plateau. Bitumen was used widely as a binding and coating material throughout the Mesopotamian plain. The tower, referred to by the Babylonians as Etemenanki, was only one of the marvels of the city. Down the street was the Hanging Gardens, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Nebuchadnezzar also had two impressive palaces inside the city. The final beginning of the end of the tower of Babel probably began around 478 BC. The city had been taken over by the Persian King Xerxes who crushed a rebellion there that year. The tower was neglected and crumbled . Because of the use of mud-baked bricks, ziggurats needed constant maintenance. Often they had elaborate internal drainage systems to channel rain water away so that the bricks would not be eroded. If the pipes on a ziggurat were not cleaned regularly and allowed to jam the tower would slowly crumble. Ziggurats were also highly susceptible to earthquake damage. Their height amplified the effect of quake forces while the rigid, unreinforced-brick construction did not allow the structures to flex with the shaking. Although the Tower of Babel now gone, a few lessor ziggurats still exist. The largest surviving, (although damaged) temple is now found in western Iran, in what was once the ancient land of Elam. It is located about 18 miles from the capital of Elam, a city named Susa. Built in 1250 BC by the King Untash-Napirisha it once had five levels and stood 170 feet in height.

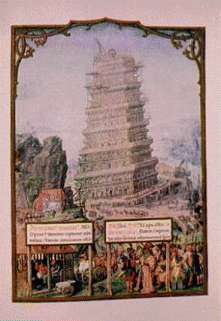

Even in 460 BC, after the tower had been crumbling for many years, the Greek historian Herodotus visited the tower and was very impressed. "It has a solid central tower, one furlong square, with a second erected on top of it and then a third, and so on up to eight. All eight towers can be climbed by a spiral way running around the outside, and about halfway up there are seats for those who make the journey to rest on." Though the tower has been gone for many years, its biblical story has continued to inspire artists. It was a favorite subject during the 14th century when several well-known paintings were done. As archaeological and historical research has shown most were not truly representative of the actual building. Copyright Lee Krystek 1997-1998. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|

Archaeologists

examining the remains of the city of Babylon have found what

appears to be the foundation of the tower: a square of earthen

embankments some three-hundred feet on each side. The tower's

most splendid incarnation was probably under King Nebuchadnezzar

II who lived from 605-562 BC. The King rebuilt the tower to

stand 295 feet high. According to an inscription made by the

king the tower was constructed of "baked brick enameled in brilliant

blue." The terraces of the tower may have also been planted

with flowers and trees.

Archaeologists

examining the remains of the city of Babylon have found what

appears to be the foundation of the tower: a square of earthen

embankments some three-hundred feet on each side. The tower's

most splendid incarnation was probably under King Nebuchadnezzar

II who lived from 605-562 BC. The King rebuilt the tower to

stand 295 feet high. According to an inscription made by the

king the tower was constructed of "baked brick enameled in brilliant

blue." The terraces of the tower may have also been planted

with flowers and trees.

What

we know about the Tower of Babel today comes only from the little

archaeological evidence found and a few ancient writings. Nebuchadnezzar

described how "gold, silver and precious stones from the mountain

and from the sea were liberally set into the foundations" and

how to rebuild it he called on "various peoples of the Empire,

from north and south, from mountains and the coasts" to help

with the construction.

What

we know about the Tower of Babel today comes only from the little

archaeological evidence found and a few ancient writings. Nebuchadnezzar

described how "gold, silver and precious stones from the mountain

and from the sea were liberally set into the foundations" and

how to rebuild it he called on "various peoples of the Empire,

from north and south, from mountains and the coasts" to help

with the construction.