pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

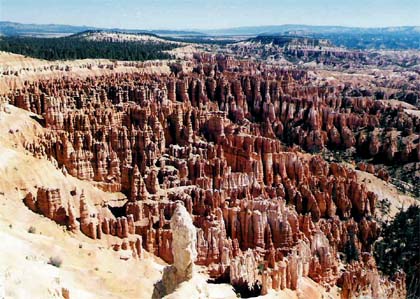

The Hoodoos of Bryce Canyon

This strange and unique landscape has been carved into haunting, colorful artwork by nature's powerful sculpture chisel, erosion. It's nowhere near as large or deep as the Grand Canyon. Nor does it have the soaring massive mountain peaks that line the walls of Zion Canyon. However, this area of southern Utah has amazing rock formations not seen at either of its more famous neighbors. Rock formations so unusual and colorful that they are not really duplicated anywhere else on the entire planet. Bryce Canyon is not really a canyon at all. It is more correctly an ampitheater cut ino the edge of a plateau by the work of wind and rain. This bowl-shaped area is three miles long, two miles wide and about 1,000 feet deep. Running out from the plateau rim are countless, tall, red-stone formations that stand up like sentinels. Some are connected as sharp ridges; others have broken away from the rest and stand alone. Erosion has sculptured these formations into fantastic shapes that resemble the work of a surrealist artist. Before Europeans came to the region a Native American tribe, the Paiute, lived in the area. They gave the "canyon" several colorful names including Anka-tompi-wawitz-pokitch, which means "many red rocks in a hole" and Anka-ka-was-a-wits which translates to "red painted faces." Perhaps the most fitting, though, translated to "bowl-shaped canyon filled with red rocks standing up like men." Nobody is exactly sure who the first Europeans were that visited the canyon, but government survey parties described the canyon in several reports between 1870 and 1876. In one of the reports, surveyor T.C. Baily observed that it looked like: …thousands of colored rocks resembling sentinels on the walls of castles…This is the wildest and most wonderful scene that the eye of man ever beheld. In 1875 a Mormon pioneer named Ebenezer Bryce and his wife Mary were sent to help settle the area. Bryce located his farm just below the ampitheater. It is said that Bryce, on seeing the canyon with its maze of high, sharp walls, observed, "It would be a terrible place to lose a cow!" Bryce's neighbors took to referring to the area with the strange red rocks as "Bryce's Canyon" and the name stuck, though Bryce only lived there for five years. In 1923 the area was made into a national monument and in 1928 a national park. The park also bears Bryce's name. Geology The unusual rock formations at Bryce are the result of the unique geological history. The story starts about 144 million years ago during the Cretaceous Period. At that time, a shallow sea covered the region. Great marine reptiles, relatives of the dinosaurs living on land, made this area their home. Their fossils can still be found embedded in the rocks laid down during this period. Over millions of years layers of mud and silt collected on the bottom of this sea. The layers varied in thickness and composition as the sea repeatedly entered the area and retreated. The dull, brown material laid down during this era makes up the canyon floor.

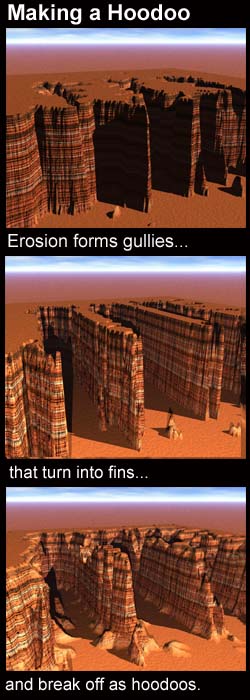

Over time pressures below the earth forced portions of the old sea bottom upward on an angle to form what's now known as the High Plateaus of Utah. The highest point in the park at the southern tip of the Paunsaugunt Plateau now has an altitude of over 9,000 feet. The top of the plateau is at an angle and drops to around 8,000 feet at the northern end. It is below the eastern rim of this section of the plateau that the pink cliffs that form Bryce Canyon can be found. Erosion is the artist responsible for carving the canyon's fantastically-shaped pillars which are known as hoodoos. Water can seep into cracks in the rock and dissolve the natural cement that bonds the rock particles together. Later, rains can wash away those particles and they wash down the canyon acting like sandpaper to further erode the rock. Also, during the winter if water gets into cracks in the rock it can freeze, splitting the stone apart. Conditions along the rim of a canyon are optimal for the work of erosion. Water racing down the steep slopes finds natural fault lines in the rock that are widened into gullies. The harder rock on either side of the gullies turns into fins. These fins are then subjected to erosion themselves which turns them into tall sets of connected natural columns. Since the layers of which the rocks are formed vary in hardness, lower portions of the columns may erode faster than upper sections, giving them their strange shapes. A fin will eventually have vertical cracks appear in it that may go completely through the rock to create a window or arch. When the window grows big enough to separate a single pillar from the rest of the fin, a solitary hoodoo is formed. Castles & Queens The fins and hoodoos act like a Rorschach Test and people can find any number of shapes in the rocks. A number of them have been named for castles - Fairy Castle, Queen's Castle, and Oastler Castle. Another is thought to look like a giant pipe organ. At the end of one trail an area named the "Queens Garden" is a hoodoo said to look like Queen Victoria.

Visitors can hike a number of trails through the canyon that give them a perspective that cannot be gained from the rim. The trails wind around the fins and hoodoos so that they tower above the hikers. Unlike the hiking in the Grand Canyon where a half-hour walk will barely take a hiker below the rim, thirty minutes is sufficient to reach much of the floor of Bryce. Visitors should not be lulled into forgetting hiking precautions, however. It is important to stay on marked trails, bring water, and be prepared to have to rest frequently on the way up. The altitude, (8,000 feet) can make climbing back out quite an effort. The hoodoos of Bryce Canyon continue to erode and change. Wind and rain removed approximately the thickness of a sheet of paper from them each year. In 10,000 years, Bryce Canyon will look significantly different than it does today. Eventually the forces of erosion, which work very slowly, but surely, will wash away the whole ampitheather. That won't happen for millions of years, however. There's plenty of time to travel to this unique geological region and visit with the hoodoos. A Partial Bibliography Geology Fieldnotes: Bryce Canyon, National Park Service, http://www2.nature.nps.gov/geology/parks/brca/ Our Country's National Parks, by Irving Robert Melbo, Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1960.

Copyright Lee Krystek, 2005. All Rights Reserved |

|

Related Links |

|

|

During

the Tertiary Period, between 66 and 40 million years ago, highlands

to the west eroded, and the dirt that flowed into the sea was

rich with iron ore. This caused the sediments being deposited

on the bottom to also become iron-rich. After millions of years

this material was compressed into a type of rock called sandstone.

When exposed to the erosion, the iron in the sandstone would rust

and give the rock a pinkish color. These layers of rock would

be named the Claron Formation and are the layers that make up

Bryce's fantastic formations.

During

the Tertiary Period, between 66 and 40 million years ago, highlands

to the west eroded, and the dirt that flowed into the sea was

rich with iron ore. This caused the sediments being deposited

on the bottom to also become iron-rich. After millions of years

this material was compressed into a type of rock called sandstone.

When exposed to the erosion, the iron in the sandstone would rust

and give the rock a pinkish color. These layers of rock would

be named the Claron Formation and are the layers that make up

Bryce's fantastic formations.