pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

The Mysterious Treasure of the Copper Scroll

|

|

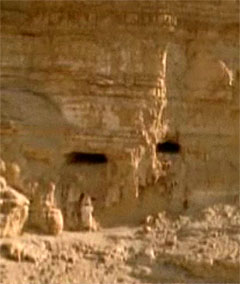

Caves at Wadi Qumran where the dead sea scrolls, including the Copper Scroll, were found. |

Item Seven: In the cavity of the Old House of Tribute, in the Chain Platform: sixty-five bars of gold.

The copper scroll was discovered in 1952 by an expedition sponsored by the Jordan Department of Antiquities. When it was found, it was in two parts. Apparently when the scroll was being rolled up, the thin copper sheet snapped into two sections. After almost two-thousand years in the cave, the document was so badly oxidized that it would crumble if anyone attempted to open it. Even while it was still wound up, though, it became apparent to scholars studying what little text could be seen that the scroll was a list of treasure. Despite great enthusiasm to unwind the document and examine the contents, no method could be found that would preserve the manuscript from harm. Finally, after four years of debate, it was decided to send the scroll to Manchester College of Technology in England and have it opened by using a saw to cut it into sections.

All of the Dead Sea Scrolls were assigned to be translated and published by a scholarly editing team. Each member of the team could choose to take as much time as they wished to produce a translation of the scrolls. Until they published no outside scholar could examine the original texts. The scholar assigned to the copper scroll was a man named J. T. Milik. However, another member of the editing team, John Allegro, was very excited by the document and went to England to be present when the manuscript was cut open.

The rest of the editing team did not share Allegro's excitement about the scroll. Supporters of Allegro say that Milik purposely withheld his translation for years longer that necessary to make it difficult for Allegro to issue one of his own. In any case, Allegro published his own translation in 1960, two years before the official one from Milik (though after a preliminary translation by Milik). Needless to say this caused a tremendous controversy.

Item 12: In the court of [unreadable], nine cubits under the southern corner: gold and silver vessels for tithe, sprinkling basins, cups, sacrificial bowls, libations vessels; in all, six hundred and nine.

It was Milik's opinion that the treasure in the list was only imaginary. There was a tradition of stories in Jewish folklore that describe how treasures from the first temple were hidden. Those objects sometimes included the Ark, the incense alter and Menorah. They were often hidden by a famous biblical figure like Jeremiah. It was Milik's contention that the copper scroll was just another of these stories.

|

The copper scroll had to be cut in half in order to open it so that it could be read. |

Allegro was of just the opposite belief and with good reason. The treasure stories from the first temple period were works of literature. The copper scroll had all the literary value of a tax return. It had no preamble. No story. No famous figure hiding legendary relics. It was simply a list of 64 locations and an accounting of objects hidden in each place. As scroll expert Dr. P. Kyle McCarter Jr. once put it, "...it is extremely difficult to imagine that anyone would have gone to the trouble to prepare a costly sheet of pure copper and imprint it with an extensive and sober list of locations unless he had been entrusted with hiding a real and immensely valuable treasure and wanted to make a record of this work that could withstand the ravages of time."

Item 14: In the pit which is to the north of Esplanade tithe vessels and garments. Its entrance is under the western corner.

If the scroll does list a real treasure, to whom did the treasure belong? Ruins at Qumran are thought to be the remains of a sect of Jews known as the Essenes. Most of the Dead Sea Scrolls found near Qumran are believed to be from their library at Qumran. The texts were probably hidden in preparation for an attack by Roman soldiers who were systematically putting down a rebellion in the land.

Did the treasure belong to the Essenes at Qumran? Probably not. The treasure is much too big to have been accumulated by such a small community. By Milik's count, some 4,630 talents of gold and silver are listed on the scroll. Though nobody is exactly sure how much a talent was at the time the scroll was written, the figure lies somewhere between twenty-five to seventy-five pounds. This would mean the treasure could consist of between 58 and 174 tons of precious metal.

There was probably only one organization in Israel at the time that could command anywhere near that amount of money: the temple at Jerusalem itself. But why would the instructions to find a treasure from Jerusalem be found many miles away at Qumran?

|

The

Dome of the Rock is now on the temple mount in Jerusalem

where the Second Temple with its treasures was once located.

|

One suggestion made by researcher Manfred Lehmann is that the treasure consisted of funds accumulated throughout Israel from about 70 to 130 AD. This was a time between two major revolts in Israel against the Romans. During this period taxes and tithes were still being collected to support the temple, but the temple had been destroyed. Since the collectors could not deliver the treasure, they buried it.

Some of the evidence suggests that the scroll was placed in the cave around 70 AD. If this was the case, the period where the treasure was gathered might have been earlier, perhaps 25 to 75 AD. If this was so, the treasure might have already been at the temple, but dispersed and buried with the expectation that the Romans would attack the city to put down a revolt, something they did in 70 AD.

"If we want to imagine how the Copper Scroll came into being," says Albert Wolters of Redeemer University College, "the thing that we should think of is probably a high ranking priest sitting there thinking, 'How can I prevent this treasure from falling into the hands of the Romans?' And then devising the plan to find various kinds of hiding places in the outskirts of Jerusalem and the Judean Desert and squirreling away these treasures."

Wolther thinks that after the priest had identified the hiding places and what was hidden there, he would have written them down on a regular piece of parchment. He would have then hired a metal worker, for security reasons perhaps one that couldn't even read the language in which the scroll was written, and have him copy the markings onto a sheet of copper.

Item 32: In the cave that is next to [unreadable] belonging to the House of Hakkoz, dig six cubits. There are six bars of gold.

|

A small earthen vessel found in a cave near Qumran by Vendyl Jones. Part of the treasure? (Copyright VJRI, photographer Yosi Cohen). |

The fact that some of the treasure was buried on the property of the House of Hakkoz is significant. Hakkoz was a priestly family who traced their lineage back to the time of King David. Later biblical references indicate that they were disqualified from priestly duties because of a problem with their genealogy. The family was probably assigned another important role in the temple. Some biblical references suggest they were the treasurers in the temple.If so, then the fact that some of the copper scroll treasure was buried on Hakkoz land provides a definite link between it and the temple.

Some argue that the amount of treasure involved is too large even to be the temple treasury. This was one of the facts cited by Milik to support his idea that the treasure is imaginary. It is likely, though, that the amounts reported in the copper scroll are somehow encoded and may not represent the actual values. Allegro noted that monetary values often varied depending on the region and that the "talent" mentioned on the scroll might be the equivalent of a smaller unit known as a "maneh." Such a reduction would yield a more reasonable, but still large, hoard of treasure.

Item 37: In the stubble field of the Shaveh, facing southwest, in an underground passage looking north, buried at twenty-four cubits: 67 talents.

After finishing his initial translation and sending it back to the authorities in Jordan, Allegro was surprised to see an official press release stating that the treasure mentioned in the copper scroll was without a doubt completely imaginary. He theorized that the official statement had been crafted to avoid setting off a treasure hunt throughout the region that might have destroyed important archaeological sites.

If that was the purpose of the release, it didn't work on Allegro. He soon gathered some help and in late 1959, to the chagrin of his colleagues, set out to find the treasure.

Allegro knew it would be extremely difficult to pinpoint the locations mentioned on the scroll. In the course of almost two-thousand years, the names of places often changed. Old names might now be attached to new locations. Others had disappeared completely. Still, he had some ideas about where to look for some of the items, and he followed up on his hunches.

The first item on the scroll had read:

Item 1: In the fortress which is in the Vale of Achor, forty cubits under the steps entering to the east: a money chest and its contents, of a weight of seventeen talents.

|

The two entrances to the "Cave of Letters." Could this also be the ancient "Cave of the Column?" |

Allegro was certain that the Vale of Achor (which means "Trouble") was a plain near Qumran. There was only one major fortress there, a defense post on top of a cone-shaped hill. In ancient days it had been known as Hyrcania. Now it was called Khirber Mird. This led Allegro's group to a vaulted underground room in the fortress some forty-feet long, sixteen-feet wide and twenty-five feet high. Unfortunately they had no way of knowing where the original eastern entrance lay, so they were unable to guess at the location of the chest, if it was still there.

The group held out hope that they might be able to locate the next item on the list which Allegro thought was probably also somewhere in Khirber Mird.

Item 2: In the sepulchral monument, in the third course of stones: 100 bars of gold.

On the southwest edge of the fortress was a mound of rubble on top of a small hill. Allegro thought that this might be the monument. Unfortunately, the metal detector they had with them was affected by the natural magnetism of the rock and they couldn't get a reading on any metal in the monument. Fortunately they decided against tearing down the whole monument to look for treasure that might not be there. Allegro's group visited other locations, but was unable to find any of the treasure and eventually gave up the search.

In 1964 another man became intrigued with the copper scroll. Vendyl Jones, a former Baptist minister from Texas turned archaeologist, started looking for some of the items mentioned on the scroll. More than twenty years later, in 1988, his excavation team found a small earthen vessel in a cave near Qumran. The jug was filled with a dark liquid substance. Analysis of the material showed that it was a sweet-smelling oil probably used in the temple to cover sacrifices. Jones believes that this jug and its sacred contents was one of the items listed in the copper scroll.

Item 25: In the Cave of the Column of two openings, facing east, at the northern opening is buried, at three cubits, a ritual limestone vessel. In it is one scroll; underneath is treasure.

|

The Arch of Titus shows the treasures being taken from the temple in Jerusalem. |

Jones isn't the only one who thinks he's stumbled across part of the treasure. Richard Freund of the University of Hartford believes that an expedition in 1960 to a remote location that became known as the "cave of letters" may have recovered ritual items from the temple. The description of the "Cave of the Column of Two Openings" bears a tremendous resemblance to the "cave of letters" which also has two openings separated by a column-like section of cliff. The 1960 expedition found a hoard of bronze implements buried at a depth of four and one half feet (three cubits) near the northern entrance to the cave along with remains of a stoneware jar and fragments of a scroll. Archeologists from the 1960 expedition identified the bronze objects as Roman ritual items which they assumed had been stolen by rebels during a revolt in 132 AD. The items, which are now housed in Israel Museum's Shrine of the Book, are covered with pagan images. For example, a shallow dish carries a depiction of the Roman sea goddess Thetis, mother of Achilles.

Freund, however, thinks that it would have been illogical for the rebels to hide Roman items. They would have simply melted them down so they could reuse the valuable bronze. He argues that the objects were actually part of the Jewish temple treasure and were actually buried earlier, either during the revolt in 70 A.D or shortly before it.

Why would pagan images be on Jewish Temple items? Freund argues, "King Herod [who built the temple] was not your classic Jewish King David or King Solomon. He was an extremely Romanized Jew who wanted his temple to reflect the values and aesthetics of Roman culture as much as it would reflect some of the culture and art and artifacts and aesthetics of Jewish culture."

To prove this line of reasoning Freund points to the carving of the Jewish menorah on the Arch of Titus in Rome. The arch, which was built to commemorate Titus and his victory over the Jews in 70 AD has a panel that shows spoils being taken from the Sack of Jerusalem. On base of the temple's menorah is an image of the Roman goddess Thetis.

Other scholars disagree and are skeptical that the Jews of the time would have tolerated Roman images on sacred ritual objects. Freund continues to look for evidence to prove his claim.

Will the other locations mentioned on the list be found and the treasure recovered? One of the most intriguing ideas about the treasure is inspired by the last entry on the list.

|

The menorah from the Arch of Titus shows pagan images on its base. |

Item 64: In a pit adjoining on the north, in a hole opening northward, and buried at its mouth: a copy of this document, with an explanation and their measurements, and an inventory of each and every thing.

This entry seems to imply that there is another copy of the scroll with more complete information. In fact, some have suggested that neither the original copper scroll, nor the one mentioned in entry 64 are sufficient by themselves to locate all the treasure. Only someone with both can hope to recover these lost riches.

If this is the case, does the duplicate scroll await a finder? Is it still buried in its hole? Or perhaps it is hidden underneath the floor boards of an antique dealer's home awaiting a buyer to offer the owner the right price. Or perhaps it has been destroyed forever, closing the chapter on this mysterious treasure of the copper scroll. .

Copyright Lee Krystek 1999-2010. All Rights Reserved.

|

Related Links |

|

|