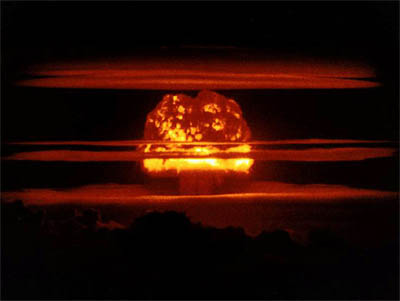

|

A

four megaton H-bomb, like this test shot called Castle

Union, creates a fireball one mile wide and, according

to one expert, can have a 100% kill zone as far away as

seventeen miles. (USAF)

|

The Day

the U.S. Air Force Almost Nuked North Carolina

On the morning of January 23rd, 1961, First Lt.

Adam Mattocks climbed aboard his B-52G Stratofortress bomber

at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base in North Carolina. Mattocks,

under the command of Major W. S. Tulloch, was one of three pilots

that was assigned to take the plane on a routine training mission

that day. What would follow over the next twenty-four hours,

however, would be anything but routine. At the end Mattocks

would be the survivor of one of the most serious nuclear weapons

accidents ever and a large part of the great state of North

Carolina would have come unbelievably close to being turned

into a smoldering, burned out, radiation-poisoned, death zone.

The

Crash

The B-52 was flying that day as part of Operation

Coverall, an airborne alert training mission on the Atlantic

seaboard involving a large portion of the Strategic Air Command's

fleet of nuclear bombers. The mission was designed to practice

keeping as many bombers in the air as possible on a continual

basis. This was so that during an actual nuclear threat they

would not be caught on the ground by a Soviet atomic strike.

Because the planes needed to keep flying hour-after-hour without

landing, they were being refueled in the air.

At just after midnight on the 24th, a KC-135 tanker

rendezvoused with Mattock's B-52 to refuel it. This involved

a boom being lowered from the rear of the tanker to a receptacle

located on the top of the B-52 just to the rear of the cockpit.

Before the refueling could start, however, the boom operator

noticed a stream of pink liquid spewing from the B-52's right

wing: a fuel leak. After hearing this information, SAC headquarters

ordered Mattocks' bomber into a holding pattern over the Atlantic

Ocean where it would wait until it had lost enough fuel to attempt

a safe landing back at base.

|

A

B-52 bomber similar to the one that broke up over North

Carolina on January 24th, 1961. (USAF)

|

The leak worsened, however, and it soon became

apparent that the Stratofortress needed to land immediately.

Under orders, the crew turned the bomber westward with the intention

of landing back at Seymour Johnson, located near Goldsboro,

North Carolina.

The B-52G they were flying that night was the

first model of the plane that used integral fuel tanks in the

wings. This greatly increased the range of the plane, but put

a huge stress on the wing structure. As the plane descended

to 10,000 feet approaching the airbase, the right wing gave

out completely and the plane broke up in mid-air. The crew tried

to bail out. Of the eight men onboard, five survived. Mattock

got out by climbing out of the B-52's top hatch and jumping

with his parachute. He was the only man ever to pull off that

stunt without an ejection seat.

Twin

Four Megaton Bombs

The whole incident might have been simply an unfortunate,

tragic, but not uncommon training accident if it hadn't been

for what the B-52G had been carrying: Two Mark 39 nuclear bombs

with a combined yield of around 8 megatons: the equivalent of

8 million tons of TNT that had more power than 500 Hiroshima-type

bombs put together.

The bombs separated from the remains of the aircraft

and plummeted toward the ground landing about 12 miles north

of the city of Goldsboro in some farm fields. According to official

word at the time, the devices were unarmed and there was never

any danger of accidental detonation.

In reality, the situation was quite a bit more

complicated.

|

The

second H-bomb landed intact after its parachute deployed

as part of its arming sequence. (USAF)

|

One of the bombs simply fell straight down. Given

its streamlined casing, it is estimated it hit the ground at

nearly 700 miles an hour. The bomb disintegrated, driving itself

many yards into the earth. Its tail was found 20 feet below

the surface. This sounds terribly dangerous, but the truth is

that despite the tremendous shock, none of the conventional

explosives designed to trigger the nuclear explosion went off.

What happened with the second bomb, however was

a lot more scary.

Large thermonuclear bombs, when dropped from

an aircraft, require a parachute to retard, or slow, the bomb's

fall so that the aircraft has sufficient time to get out of

the blast zone. The parachute will not deploy on a fully-unarmed

bomb, as in the case of the first Mark 39 mentioned above.

On the second bomb, however, the retardation parachute

did deploy, indicating that the bomb went through at least part

of its arming sequence. The device's parachute snagged on a

tree and this left the bomb hanging with just the bottom 18

inches of the nose buried in the ground. Otherwise it was completely

intact.

Obviously, since the bomb didn't detonate, it

hadn't been completely armed. The fact that the bomb had even

partly gone through its arming procedure, however, was alarming

to USAF officials and the details of what actually happened

inside the nuclear device became a closely-guarded secret.

Four

Megaton Blast Effects

What would have happened to North Carolina if

the second bomb had detonated is well-known from extensive tests

performed in the Pacific in previous decades. The explosion

from a four megaton device would have created a fireball over

a mile in diameter. With a temperature of 20 million degrees

fahrenheit, everything inside would have been vaporized. Heat

and a titanic shock wave would have killed everyone out to a

distance of two and a half miles from ground zero within seconds.

The small towns of Faro and Eureka would simply have ceased

to exist as a blast of pressurized air traveling nearly at the

speed of sound flattened even reinforced concrete and steel

structures.

The heat would have been so intense that even

at the outskirts of Goldsboro, seven miles away, the sheet metal

on the exterior of vehicles would have melted. The whole of

the town of Goldsboro would have been subjected to intense thermal

radiation that would have ignited all easily-flammable materials

including wood, paper, cloth, leaves, gasoline and heating fuel.

As these individual fires merged, an effect called a firestorm

would have occurred. Anybody seeking shelter in a basement would

most likely been roasted alive by the intense heat or suffocated

as the flames consumed all of the oxygen in the air. Anyone

within fourteen miles who was exposed to the blast would have

sustained third degree burns. It is likely that very few people

in the city would have survived. One expert estimated that the

bomb was large enough to have a 100% kill zone within seventeen

miles of the detonation point, an area that completely enveloped

the Goldsboro and its suburbs. By some estimates, 60,000 would

have died from the bomb in the vicinity of Goldsboro.

Lt. Jack Revelle, the bomb disposal expert responsible

for disarming the devices, once said, "As far as I'm concerned,

we came damn close to having a Bay of North Carolina. The nuclear

explosion would have completely changed the Eastern seaboard

if it had gone off." While North Carolina being turned into

an arm of the Atlantic Ocean seems a bit of an exaggeration,

there is no doubt that the entire United States East coast would

have been under threat from the explosion's fallout.

|

What

About Those "Nuclear Codes?"

A

Permissive Action Link (PAL) is a security system

designed so that a nuclear warhead cannot be detonated

without presidential authorization. The code (usually

four digits) is used to prevent renegade military personnel,

or terrorists who have stolen a bomb, from detonating

it. The warheads are also designed so they cannot be "hotwired"

bypassing the PAL. If the bomb is tampered with, it is

disabled. For security reasons the methods used to disable

it are unknown, but it is speculated that one method is

a small charge that can be set off near the bomb's nuclear

core damaging it. After that, the bomb could not be used

without being rebuilt, though the nuclear material could

be salvaged.

While

a PAL system is not designed to prevent an explosion due

to an accident, depending on its design it might create

another layer of protection in that scenario. Unfortunately,

the MK-39 involved in the Goldsboro incident was designed

and built long before PALs were engineered into nuclear

warheads and they were not a factor in the accident.

|

Radiation from a nuclear blast comes in two forms.

First is the "flash" that comes directly from the bomb when

it detonates. Then, in the period after the actual explosion,

"fall out" can blanket the surrounding area. Fall out occurs

when the radioactive residue which is propelled up into the

atmosphere by the explosion "falls out" of the sky down to earth

in the days and weeks following the detonation. These two sources

of radiation can be as deadly as the heat and blast effects

from the explosion itself. At Hiroshima in World War II it is

estimated that over half the people who died weren't killed

by the blast effects, but succumbed to radiation sickness in

the hours, weeks or months following the dropping of the bomb.

Fallout from a blast near Goldsboro could have

blanketed much of the East Coast with deadly effects depending

on the wind and weather conditions following the detonation.

It is estimated that the cloud could have reached as far as

Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia and even New York City.

How

Close Did It Come To Detonation?

Although the basic information of what happened

over Goldsboro in 1961 has been known for decades, some of the

most important (and scary) details became public only recently.

Investigative journalist Eric Schlosser, while researching his

book Command and Control, was able to obtain a classified

report on the incident under the Freedom of Information Act.

The account was written by Parker F Jones for the U.S. government

eight years after the incident. Jones, a senior engineer in

the Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, N.M, was a

leading expert on atomic weapons safety and his department was

in charge of the mechanical aspects of nuclear devices. He entitled

his work Goldsboro Revisited or: How I learned to Mistrust

the H-Bomb (a spoof on Stanley Kubrick's satirical film

title Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying

and Love the Bomb). Jones found that on the second bomb

three of the four safety systems that were designed into it

to keep it from detonating accidentally failed. The fourth,

a simple, low-voltage switch, was all that stopped Armageddon

from happening in North Carolina that day.

Parker found that the switch that prevented detonation

could have easily been shorted by an electrical jolt, leading

to an accidental detonation. "It would have been bad news -

in spades," he wrote in his report. When the bomb touched down,

a firing signal was sent to the nuclear core of the device,

and it was only this single switch that prevented catastrophe.

"The MK 39 Mod 2 bomb did not possess adequate safety for the

airborne alert role in the B-52," Jones concluded.

Perhaps as terrifying as this is what they found

when they excavated the first bomb from the hole that it had

dug for itself in the farmer's field. The bomb went so far into

the ground, and the water table was so high, that some parts

of the device were never recovered. The best the Army Corps

of Engineers could do was buy an easement from the farmer that

forbids digging deeper than five feet. To this day, the North

Carolina government continues to test the area for signs of

radioactive contamination.

|

On

the buried bomb the arm/safe switch was found to be in

the armed position. (USAF)

|

One part that was found, however, was the same

low-voltage switch that had prevented detonation in the second

bomb. ReVelle, who was in charge of the recovery, recalled the

moment when the switch was located. "Until my death I will never

forget hearing my sergeant say, 'Lieutenant, we found the arm/safe

switch.' And I said, 'Great.' He said, 'Not great. It's on arm."

ReVelle later remarked on the second bomb, "How close was it

to exploding? My opinion is damn close."

The same switch that prevented detonation on the

second bomb actually failed on the first bomb. Therefore it

isn't surprising Jones reached the conclusion on his report

that on that day just "one simple, dynamo-technology, low voltage

switch stood between the United States and a major catastrophe."

Copyright Lee Krystek

2013. All Rights Reserved.