|

This

print shows the Hindenburg in flames above Lakehurst

Naval Air Station on May 6th, 1937. (The

National Archives)

|

The

Mystery of the Hindenburg Disaster

It was the largest airship ever built; over eight-hundred

feet long from its nose to its massive tail fins. It was the

height of luxury travel and in the course of two seasons carried

over 2,656 people across the Atlantic between Germany to New

York and Rio de Janeiro. It was called the Hindenburg and the

space of 37 seconds this mighty zeppelin was destroyed in a

fire that killed a third of its crew and passengers and left

spectators crying in horror.

What caused this catastrophe? Was it negligence,

sabotage, or as Hitler called it, "An act of God"?

The

Dirigible

The first successful dirigible (a balloon that

has engines to control its horizontal movement) was built in

France in 1852. Although other countries built these types of

airships, the Germans quickly became the most advanced builders

of this form of lighter-than-air technology. Count Ferdinand

von Zeppelin, a German businessman, built a fleet of experimental

dirigibles. The type of airships Zeppelin built were spindle-shaped

with a rigid internal steel structure (unlike the flexible bodied

blimps common today). Inside the craft were large bags filled

with gas that gave the ship its lift, as well as catwalks to

allow the crew to move back and forth inside the hull to service

the airship. Beneath the craft was a gondola which carried the

crew and passengers. By 1911 Zeppelin's airship LZ-10 (also

known as the Schwaben) was in passenger service and would go

onto make 218 flights carrying 1,553 passengers. Zeppelin became

so well-known for this type of dirigible that his name soon

became synonymous with that type of airship.

Starting in 1914, the beginning of WWI, the Count's

zeppelins were used to drop bombs on cities in a number of European

countries. They made over fifty raids on London alone, dropping

nearly 200 tons of explosives. As the war progressed, however,

most of the German's zeppelin fleet was destroyed by British

guns or aircraft. The gas that gave them their lift, hydrogen,

was very flammable, and even a small bomb hitting a zeppelin

could reduce it to ashes in just a few minutes.

|

The

LZ7, one of Count Zeppelin's early ships (also known as

the Deutschland), can be considered the first true

passenger aircraft. It first flew on October 19th, 1910.

|

After the war Germany again began building large

airships. As part of war reparations the Germans built the ZR-3

Los Angeles for the U.S. Navy. In 1928 the Zeppelin Company

built what was the most successful passenger dirigible of all

time, the Graf Zeppelin.

The Graf Zeppelin was a hundred feet longer than

any other airship ever built and stretched 776 feet from nose

to tail fins. It was designed as a passenger liner to compete

with the ocean liners crossing the Atlantic. With a maximum

speed of 80 miles per hour, it cut the time it took to make

the trip by more than two-thirds. The passenger cabin was outfitted

with drapes and thick carpeting. Dinner was made by professional

chefs and was served using silverware, crystal and fine china.

Time magazine declared, "Certainly for trans-oceanic trips,

the airship is the thing."

Constructing

The Hindenburg

The Graf Zeppelin was so successful that the Zeppelin

Company planned a new airship. One that would be bigger, faster

and carry more passengers with more luxurious amenities. It

would be named after a national hero who had been elected Germany's

president in 1925. It would be called the Hindenburg.

The Hindenburg was not only longer than the Graf

Zeppelin, it was an extra 35 feet wide. This meant it had nearly

twice the volume for lifting gas (7,062,000 cubic feet) than

the Graf Zeppelin. There was a reason for this. The Hindenburg's

designers had decided to fill the new dirigible with helium

gas, not hydrogen. Helium, unlike hydrogen, does not burn, making

it safer. However, it doesn't produce as much lift as hydrogen,

so the extra volume the Hindenburg had for gas was an important

feature.

The Hindenburg never got its helium, though. At

that time helium was difficult to produce and the United States

had a monopoly on the manufacture of it. When the Americans

saw that Hitler was in power in Germany, they feared he would

use the gas for military purposes and therefore would not sell

the Germans the helium necessary to fill the Hindenburg. The

Zeppelin Company was forced to redesign the ship for hydrogen

and make changes to minimize the possibility of fire.

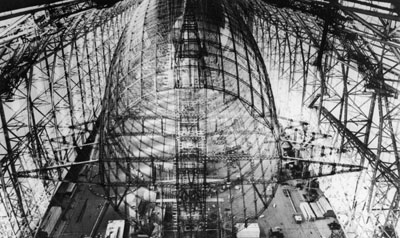

|

The

frame of the Hindenburg under construction. (Credit:

Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1986-127-05 / CC-BY-SA)

|

Though it might seem strange to us today, back

then the airship seemed to be the wave of the future in travel.

At that time crossing the Atlantic in an airplane was risky

business. Planes could travel only short distances carrying

a minimum of weight and required constant refueling. To many

the zeppelins was the natural successor to the ocean liner.

The Zeppelin Company planned that the Hindenburg would be the

first of a fleet of airships plying the skies of the world.

Even today the Hindenburg remains the largest

aircraft ever flown. Some of the smaller, modern advertising

blimps have a total length only slightly larger than the girth

of the Hindenburg. If the Hindenburg stood on end it would dwarf

the Washington Monument. It could lift 112 tons beyond its own

weight, an incredible amount for that time. Passengers enjoyed

staterooms with private showers. The dining room served the

finest food on blue and gold porcelain place settings. The ship

provided the passengers a spectacular view along its windowed

200-foot-long promenade deck. One restriction the ship had though

was smoking. Because of the hydrogen, smoking was permitted

only in a special fireproof room.

Final

Flight

A one-way trip across the Atlantic cost $400 and

took only two days. Flights began in 1936 with the airship making

a total of six trips to Rio de Janeiro and ten trips to New

York City carrying a total of 2,656 passengers. In 1937 it made

a trip to Rio then returned to Germany. On May 3rd, 1937, the

Zeppelin departed Frankfurt for North America carrying 97 people.

It would be the first trip to New York City that season.

The trip went smoothly and by 11:40 A.M. on May

6th the airship was passing over Boston. Landing at the Naval

Air Station in Lakehurst was delayed due to bad weather, so

the ship's captain, Commander Max Pruss, decided to linger over

New York City, giving his passengers spectacular views of the

Empire State Building, the Bronx, Harlem, Central Park, the

Battery, Times Square, the Statue of Liberty and Ebbets Field

(where a game was being played between the Dodgers and the Pittsburgh

Pirates).

At 4 P.M. the Hindenburg arrived over Lakehurst,

but the weather was still worrisome. Commander Pruss decided

to take the ship southeast until he hit shore, then north to

Asbury Park, then finally inland back to Lakehurst. At 6:12

Charles E. Rosendahl, Commanding Officer of the Lakehurst N.A.S.,

sent a message to the Hindenburg: "Conditions now considered

suitable for landing." Eleven minutes later a stronger message

followed: "Recommend landing now."

|

The

lounge of the Hindenburg allowed the passengers to watch

the view below.

|

The

Landing

It was almost a half hour later, at 7:00 P.M.,

that the Hindenburg started its landing. It circled the base,

dropping its altitude from 600 to 300 feet and aligned itself

so it was headed into the wind. As it approached the mooring

mast, Captain Pruss realized he was going a little too fast.

Also the wind was changing direction. Given that he was already

late, he decided not to do a complete go around, but slow the

ship and change his approach by making a sharp "S" turn, first

left, then right.

To further complicate things for the captain,

the airship was losing trim. The tail section was dropping.

This was not particularly odd as it had been raining the water

tended to cling more to the rear of the ship than the front,

making it heavier. Puss ordered some ballast dropped and six

crewmen were sent scurrying to the bow of the dirigible to balance

it. The turn worked and the zeppelin's nose finally faced the

mooring mast where it would be secured. As the Hindenburg got

within 700 feet of the mast, the engines were reversed, bringing

the ship to a stop. Ropes were dropped to allow the ground crew

to tow the ship into position. At this point the Zeppelin was

hanging about 275 off the ground. It was 7:25 P.M..

On the ground a radio reporter named Herbert Morrison

was covering the airship's arrival and his comments were recorded

for prosperity:

...It's practically standing still now. They've

dropped ropes out of the nose of the ship, and it's been taken

a hold of down on the field by a number of men. It's starting

to rain again; the rain had slacked up a little bit. The back

motors of the ship are just holding it, just enough to keep

it from --"

"It burst into flames! ... It's fire and it's

crashing! It's crashing terrible! Oh, my! Get out of the way,

please! It's burning, bursting into flames and is falling on

the mooring mast, and all the folks agree that this is terrible.

This is the worst of the worst catastrophes in the world! ...There's

smoke, and there's flames, now, and the frame is crashing to

the ground, not quite to the mooring mast...Oh, the humanity,

and all the passengers screaming around here!

The flames were first visible towards the tail

of the ship, then within seconds the hydrogen in the gas bags

caught on and the whole aft of the craft was engulfed in a mass

of flame and smoke that towered hundreds of feet into the sky.

As the hydrogen in the rear of the ship burned, the rear of

the Hindenburg lost its lift and fell to the ground and its

nose pointed upwards at a forty-five degree angle. Then as the

flames raced through to the bow, it also fell. In just 37 seconds

since the first flames were spotted the ship lay on the ground,

the skeleton of its framework the only thing visible through

the fire. Passengers jumped from windows and ran for safety.

One cabin boy had his life saved when a water tank burst above

his head. Of the 97 people on board, miraculously 62 managed

to escape with their lives, including the ship's captain.

An investigation into the cause of the disaster

was made both by the United States and the German governments.

They concluded a hydrogen leak was ignited by a spark of static

electricity. Both governments wanted to close the book on the

disaster. The Americans were anxious to avoid an international

incident and the Germans were embarrassed that the cause might

have been a design flaw in the ship or the result of foul play.

The

Gas Leak Theory

Some theories suggest that Commander Pruss's final

turns to land were too sharp and they caused a support wire

to snap inside the ship tearing open one of the hydrogen gas

cells. The leaking gas then might have been set off by a rare,

natural electrical phenomenon known was St. Elmo's fire. St.

Elmo's fire is usually seen as a static electric charge around

high objects (like church steeples) during stormy weather. Given

the weather on that day, it is very likely that the ship was

carrying a static electric charge. Just before the fire broke

out, witnesses saw a fluttering movement of the ship's skin

near the rear of the vessel. Some people argue this was caused

by escaping gas. Other witnesses noticed a blue glow around

the rear of the vessel that might have been St. Elmo's fire.

If the gas escaped out a ventilation shaft and met the static

electric discharge, it might well have triggered the fire.

The

Lightning Theory

Instead of st. Elmo's Fire, lightning is sometimes

blamed as the cause of the fire. However, the Hindenburg had

been struck several times before by lightning with no damage.

If lightning was the cause of the disaster, it seems it must

have been coupled with a gas leak, as with the above theory.

However, no witnesses saw lightning strike the ship and there

were no known thunderstorms in the immediate area.

Diesel

Theory

This theory suggests that the diesel fuel used

to power the engines may have started the fire. A leak from

a malfunctioning fuel pump might have ignited if the fuel reached

a hot surface like the engine block. The pods where the engines

were housed, however, were not by all accounts the location

where the fire started.

Initially engineers suspected that sparks from

a backfiring engine might have ignited hydrogen from a leak,

but tests showed that these type of sparks were not actually

hot enough to have set the gas on fire.

The

Flammable Skin Theory

A theory suggested by Addison Bain, former manager

of NASA's hydrogen program, was that the initial fire was not

caused by burning hydrogen. Hydrogen burns without much of a

visible flame, but witnesses described the fire as extremely

colorful. Bain thinks the doping solution used to stretch and

waterproof the hull was responsible. The compound, a layer of

iron oxide covered with coats of cellulose butyrate acetate

mixed with powdered aluminum, is very similar to a mixture used

to power solid fuel rockets. "The Hindenburg was literally painted

with rocket fuel," says Bain.

Bain suspects that the Germans figured out the

real cause, though they didn't want to admit they'd made such

a dangerous mistake. The doping solution used on the Graf Zeppelin

II, completed after the Hindenburg disaster, was changed to

include a fireproofing agent and the aluminum was replaced with

bronze which is less combustible.

Bain thinks the fire was started by a build-up

of static charge from the storm on the craft's surface and frame.

When the mooring ropes (wet from the storm) were dropped to

the ground, the frame discharged, creating an electrical differential

between the frame and covering which started the fire.

|

The

remains of the Hindenburg on the ground just minutes after

the first flames appeared.

|

Tests have been run with remains of the covering,

however, that show that although it is flammable , it doesn't

burn with the speed needed to explain the rapid expansion of

the fire through the whole ship. If the fire did start with

the skin, it seems it must have ignited the hydrogen cells almost

immediately.

The

Sabotage Theory

Some of the crew that survived, including Commander

Pruss, suspected the fire was sabotage. The Hindenburg was more

than just a German airship. It was a symbol of German power

and technical prowess. Hitler's government, which had helped

pay for the Hindenburg's construction, had employed it for such

jobs as making propaganda appearances over the 1936 Olympic

Games in Berlin. Each of the huge tail fins of the Hindenburg

wore the swastika emblem, the symbol of Hitler's Nazi party.

Officials had been concerned even before the ship reached New

York that someone opposing Hitler might make a terrorist attack

upon the craft.

If a saboteur was at work, it must have been one

of the crew or passengers. If so, that person may have placed

a time bomb along one of the ship's internal catwalks. Most

likely it detonated prematurely, or the saboteur did not count

on the craft being so late at arriving and could not return

to the bomb to reset the timing mechanism. Either way the saboteur

may have died in the resulting explosion. A bomb placed near

the rear of the craft might have explained the initial flare

forward of the tail fin as reported by witnesses as flames from

the explosion shot up the gas ventilation shaft to burst out

the top of its hood. The initial explosion would have ruptured

the hydrogen gas cells, causing a more powerful second explosion

that destroyed the craft.

Suspicion for the sabotage initially fell upon

Joseph Spah, a passenger who survived. On several occasions

Spah, a New Jersey resident, had gone unescorted into the cargo

area of the ship to visit his dog that he was bringing home

to his children. This might have given him the opportunity to

place a bomb. Later, others suspected that Erich Spehl, an introverted

crewman who perished in the fire, might have been the saboteur.

Spehl was thought to have had anti-Nazi leanings.

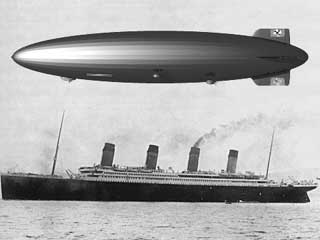

|

The

Hindenburg was nearly the size of the Titanic.

|

There is no proof against either of these gentlemen

and in a search of the wreckage no parts of a bomb were found.

Any time bomb would require a timer mechanism which probably

would have survived the explosion.

End

of An Era

Today, the official results of the investigation

that static electricity set off leaking hydrogen still stand,

despite the various theories. One thing is for sure, though,

the destruction of the Hindenburg signaled the end of the great

zeppelin passenger liners. No zeppelin ever carried another

passenger after the Hindenburg disaster. The Graf Zeppelin II

which was to be the Hindenburg's sister ship, never entered

passenger service. At the start of W.W.II, it was brought into

military service for a short time, then dismantled and the parts

used for the war effort.

By the end of the war the jet engine had been

invented and transatlantic passenger service soon was carried

out with a reliability and speed that could not be matched by

lighter-than-aircraft. Memories of the horror of the Hindenburg

disaster lingered on, killing any future for the large, rigid,

passenger airships. The zeppelin, once thought to be the wave

of the future, was suddenly a thing of the past.

Copyright 2001-2013Lee

Krystek. All Rights Reserved.