|

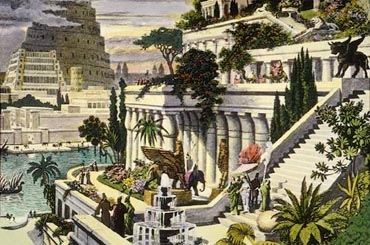

Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Video: Gift for a Queen: The Hanging Gardens The city of Babylon, under King Nebuchadnezzar II, must have been a wonder to the ancient traveler's eyes. "In addition to its size," wrote Herodotus, a Greek historian in 450 BC, "Babylon surpasses in splendor any city in the known world." Herodotus claimed the outer walls were 56 miles in length, 80 feet thick and 320 feet high. Wide enough, he said, to allow two four-horse chariots to pass each other. The city also had inner walls which were "not so thick as the first, but hardly less strong." Inside these double walls were fortresses and temples containing immense statues of solid gold. Rising above the city was the famous Tower of Babel, a temple to the god Marduk, that seemed to reach to the heavens. While archaeological excavations have disputed some of Herodotus's claims (the outer walls seem to be only 10 miles long and not nearly as high) his narrative does give us a sense of how awesome the features of the city appeared to those ancients that visited it. Strangely, however, one of the city's most spectacular sites is not even mentioned by Herodotus: The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Gift for A Homesick Wife Accounts indicate that the garden was built by King Nebuchadnezzar, who ruled the city for 43 years starting in 605 BC (There is an alternative story that the gardens were built by the Assyrian Queen Semiramis during her five year reign starting in 810 BC). This was the height of the city's power and influence and King Nebuchadnezzar is known to have constructed an astonishing array of temples, streets, palaces and walls. According to accounts, the gardens were built to cheer up Nebuchadnezzar's homesick wife, Amyitis. Amyitis, daughter of the king of the Medes, was married to Nebuchadnezzar to create an alliance between the two nations. The land she came from, though, was green, rugged and mountainous, and she found the flat, sun-baked terrain of Mesopotamia depressing. The king decided to relieve her depression by recreating her homeland through the building of an artificial mountain with rooftop gardens. The Hanging Gardens probably did not really "hang" in the sense of being suspended from cables or ropes. The name comes from an inexact translation of the Greek word kremastos, or the Latin word pensilis, which means not just "hanging", but "overhanging" as in the case of a terrace or balcony. The Greek geographer Strabo, who described the gardens in first century BC, wrote, "It consists of vaulted terraces raised one above another, and resting upon cube-shaped pillars. These are hollow and filled with earth to allow trees of the largest size to be planted. The pillars, the vaults, and terraces are constructed of baked brick and asphalt." "The ascent to the highest story is by stairs, and at their side are water engines, by means of which persons, appointed expressly for the purpose, are continually employed in raising water from the Euphrates into the garden." The Water Problem Strabo touches on what, to the ancients, was probably the most amazing part of the garden. Babylon rarely received rain and for the garden to survive, it would have had to been irrigated by using water from the nearby Euphrates River. That meant lifting the water far into the air so it could flow down through the terraces, watering the plants at each level. This was an immense task given the lack of modern engines and pressure pumps in the fifth century B.C.. One of the solutions the designers of the garden may have used to move the water, however, was a "chain pump." A chain pump is two large wheels, one above the other, connected by a chain. On the chain are hung buckets. Below the bottom wheel is a pool with the water source. As the wheel is turned, the buckets dip into the pool and pick up water. The chain then lifts them to the upper wheel, where the buckets are tipped and dumped into an upper pool. The chain then carries the empty buckets back down to be refilled. The pool at the top of the gardens could then be released by gates into channels which acted as artificial streams to water the gardens. The pump wheel below was attached to a shaft and a handle. By turning the handle, slaves provided the power to run the contraption. An alternate method of getting the water to the top of the gardens might have been a screw pump. This device looks like a trough with one end in the lower pool from which the water is taken with the other end overhanging an upper pool to which the water is being lifted. Fitting tightly into the trough is a long screw. As the screw is turned, water is caught between the blades of the screw and forced upwards. When it reaches the top, it falls into the upper pool. Turning the screw can be done by a hand crank. A different design of screw pump mounts the screw inside a tube, which takes the place of the trough. In this case the tube and screw turn together to carry the water upward. Screw pumps are very efficient ways of moving water and a number of engineers have speculated that they were used in the Hanging Gardens. Strabo even makes a reference in his narrative of the garden that might be taken as a description of such a pump. One problem with this theory, however, is that there seems to be little evidence that the screw pump was around before the Greek engineer Archimedes of Syracuse supposedly invented it around 250 B.C., more than 300 years later. Garden Construction Construction of the garden wasn't only complicated by getting the water up to the top, but also by having to avoid having the liquid ruining the foundations once it was released. Since stone was difficult to get on the Mesopotamian plain, most of the architecture in Babel utilized brick. The bricks were composed of clay mixed with chopped straw and baked in the sun. These were then joined with bitumen, a slimy substance, which acted as a mortar. Unfortunately, because of the materials they were made of, the bricks quickly dissolved when soaked with water. For most buildings in Babel this wasn't a problem because rain was so rare. However, the gardens were continually exposed to irrigation and the foundation had to be protected. Diodorus Siculus, a Greek historian, stated that the platforms on which the garden stood consisted of huge slabs of stone (otherwise unheard of in Babel), covered with layers of reed, asphalt and tiles. Over this was put "a covering with sheets of lead, that the wet which drenched through the earth might not rot the foundation. Upon all these was laid earth of a convenient depth, sufficient for the growth of the greatest trees. When the soil was laid even and smooth, it was planted with all sorts of trees, which both for greatness and beauty might delight the spectators." How big were the gardens? Diodorus tells us they were about 400 feet wide by 400 feet long and more than 80 feet high. Other accounts indicate the height was equal to the outer city walls, walls that Herodotus said were 320 feet high. In any case the gardens were an amazing sight: A green, leafy, artificial mountain rising off the plain. Were the Hanging Gardens Actually in Nineveh? But did they actually exist? Some historians argue that the gardens were only a fictional creation because they do not appear in a list of Babylonian monuments composed during that period. It is also a possibility they were mixed up with another set of gardens built by King Sennacherib in the city of Nineveh around 700 B.C.. Stephanie Dalley, an Oxford University Assyriologist, thinks that earlier sources were translated incorrectly putting the gardens about 350 miles south of their actual location at Nineveh. King Sennacherib left a number of records describing a luxurious set of gardens he'd built there in conjunction with an extensive irrigation system. In contrast Nebuchadrezzar makes no mention of gardens in his list of accomplishments at Babylon. Dalley also argues that the name "Babylon" which means "Gate of the Gods" was a title that could be applied to several Mesopotamian cities. Sennacherib apparently renamed his city gates after gods suggesting that he wished Nineveh to be considered "a Babylon" too, creating confusion. Archaeological Search These were probably some of the questions that occurred to German archaeologist Robert Koldewey in 1899. For centuries the ancient city of Babel had been nothing but a mound of muddy debris never explored by scientists. Though unlike many ancient locations, the city's position was well-known, nothing visible remained of its architecture. Koldewey dug on the Babel site for some fourteen years and unearthed many of its features including the outer walls, inner walls, foundation of the Tower of Babel, Nebuchadnezzar's palaces and the wide processional roadway which passed through the heart of the city. While excavating the Southern Citadel, Koldewey discovered a basement with fourteen large rooms with stone arch ceilings. Ancient records indicated that only two locations in the city had made use of stone, the north wall of the Northern Citadel, and the Hanging Gardens. The north wall of the Northern Citadel had already been found and had, indeed, contained stone. This made Koldewey think that he had found the cellar of the gardens. He continued exploring the area and discovered many of the features reported by Diodorus. Finally, a room was unearthed with three large, strange holes in the floor. Koldewey concluded this had been the location of the chain pumps that raised the water to the garden's roof. The foundations that Koldewey discovered measured some 100 by 150 feet. This was smaller than the measurements described by ancient historians, but still impressive. While Koldewey was convinced he'd found the gardens, some modern archaeologists call his discovery into question, arguing that this location is too far from the river to have been irrigated with the amount of water that would have been required. Also, tablets recently found at the site suggest that the location was used for administrative and storage purposes, not as a pleasure garden. If they did exist, what happened to the gardens? There is a report that they were destroyed by an earthquake in the second century B.C.. If so, the jumbled remains, mostly made of mud-brick, probably slowly eroded away with the infrequent rains. Whatever the fate of the gardens were, we can only wonder if Queen Amyitis was happy with her fantastic present, or if she continued to pine for the green mountains of her distant homeland.

|