pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

Notes from the Curator's Office:

What Ever Happened to the Rocket Belt? My father didn't get a lot of magazines when I was a kid. One he did get, however, was Popular Science. I used to love grabbing them (when Dad was done reading them) to see what new fantastic item - rocket ship, flying saucer, personal submarine - was on the cover. All these inventions seemed to be due to arrive in the year 2000, more or less. Some of my favorite contraptions that often appeared on the cover were personal flying devices: things like rocket belts, jet packs and miniature one-man helicopters. Once these things were perfected by the beginning of the 21st century, everybody, including me, would be able to fly like Superman (or superwoman). Well, the 20th century is here and these devices are still a dream. Whatever happened to the rocket belt? Buck Rogers, etc. I started looking around on the internet and found that rocket belts have been a staple of pulp science-fiction since the 1920's. Buck Rogers used a rocket belt. The movie serial King of the Rocketmen brought the idea to the silver screen in 1949. Probably the first serious attempt to actually build such a device can be credited to the Germans. During World War II there was an effort to strap two primitive pulse jet engines - one on front and one on back - to a dummy to see if a man could be made to fly. The idea was that it would be valuable for soldiers to be able to jump over mine fields, transverse rivers or fly up cliffs. Nothing much came of the device and after the war it wound up in the hands of American contractor Bell Aerosystems for a close examination by engineers. Nobody was fool enough to attempt to fly the thing, but a test with a tethered mannequin was run. The device didn't prove practical, but the idea must have stuck in the head of some of the Bell engineers. One of them, Wendell F. Moore, started designing a single-man flying machine for the Department of Defense. Moore realized that jets engines were just too bulky and too complicated at this point in their development to mount on a backpack. Instead he decided to use rockets. This would be a simpler design and give the device a better thrust-to-weight ratio -- in other words, for the same amount of weight a rocket could give more lift than a jet. The Rocket Belt The rocket fuel Moore chose was hydrogen peroxide - yep, the same stuff in your bathroom cabinet that can give your hair a bad dye job -- though at a much higher concentration. If this doesn't sound particularly high-tech, well, there were other rocket fuels that could have been used giving Moore three times the power, but they tended to be unstable and dangerous to work with. Given that the intention was to have somebody strap this thing on their back, a less-hazardous fuel seemed prudent.

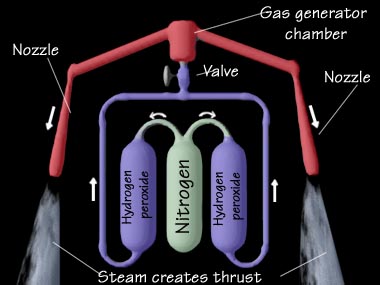

Not that hydrogen peroxide doesn't have a good kick. When a high concentration of the stuff is passed through a metal catalyst it breaks down into steam and oxygen. The steam takes up a lot more space than the original components of the hydrogen peroxide, so it goes shooting out of the rocket with quite a bit of force. The backpack was composed of three tanks. The center one was filled with pressurized nitrogen and connected to the outer ones which were filled with the hydrogen peroxide. When the time came to launch the nitrogen flowed out into the outer tanks and pushed the peroxide out two pipes that met in a Y just above the chamber containing the catalyst at the top of the pack. From that chamber the flow, now changed to high pressure steam, was split into two pipes pointed downward with nozzles located just behind the pilot's shoulders. The device was designed to create 280 pounds of thrust which was enough to lift its own weight, plus that of the pilot. The design of the motor was relatively simple, but building a way to control the belt so it could be flown safely, was more difficult. Moore originally piloted the device himself until an accident during testing broke his kneecap. Eventually an elegant control system was developed that allowed the pack and the nozzles to be swivelled to change the direction of the thrust so the pilot, using a set of hand controls, could manuver the belt up, down, foreward, back and even around in a spinning motion. Later pilots reported that the belt was very easy to control, but that they did need the protection of a thermal suit so that the steam outflow would not burn their legs.

The problem with the rocket belt was range. The rocket engine gave a lot of power, but not for very long. The maximum flight was only 21 seconds. This made for great demonstrations, but was of little practical value. Consequently the Bell rocket belt became mostly a novelty, showing up in places like movies (Thunderball), TV (Lost in Space) and special events ( the opening of the Olympics in 1984). Mainly because of the flight time limitation, the military lost interest in the rocketbelt in the mid-60's, but Moore had another idea. Jet technology had advanced a lot in the past decade. Perhaps it was time to go back and try a jet engine. The Jet Pack In 1969 Wendell Moore and John K. Hulbert of Bell Aerosystems had Williams Research Corporation design a turbojet small enough to be carried on a man's back. The jet was mounted with the intake facing the ground and the exhaust shooting upward to a pipe that split the outflow and pointed back down. Two nozzles were located just in back of the pilot's shoulders similar to those on the rocket belt. The jet had less power for its weight than the rocket engine, but also used much less fuel. Tests were carried out that showed that the pack could carry a man in the air for ten minutes, and with improvements the flight time might reach as long as a half hour (This device turns out to be the one I'd actually seen on the cover of Popular Science). The jet pack seemed to solve the biggest problem associated with the rocket belt: range. Twenty-one seconds was now thirty minutes. So why, if you parden the pun, didn't the jet pack take off? As before, the military was the primary market for the jet pack. As much as the length of flight had been improved, it still fell short of their needs. Also, the change from a rocket to a jet made the device much more complicated, difficult to service and less reliable. A large support team would be needed to keep thing running. Why commit that many people to keep a device in flight that would carry a single man when you could employ them to support a helicopter that could carry ten people?

The commercial market for the jet belt also was limited. Not only was the short flight time an issue, but there was a question of safety. If the jet pack's engine failed - which was not unlikely given the complicated design - there was no chance of the pilot gliding to safety as he might in a helicopter or an airplane. The fall would most likely be fatal, and with some jet fuel still on board, perhaps even explosive. The jet pack had a parachute system built into it but it wasn't very useful if the machine failed below a height of about 70 feet. Perhaps these problems might have been solved, but in May of 1969 Wendell Moore died of complications from a heart attack. Without his influence, the project was shelved and the single jet pack sold to Williams Research Corporation where it now sits in the company museum. Over the years other people have tried to build other personal flying machines. In 1995 a group of three men improved on Moore's original rocket belt design by using newer, lighter-weight materials. With less weight tied up in the mechanism, the device could carry more fuel, giving it a longer flight time of 30 seconds. They named the device the RB2000 Rocket Belt, and it might have become popular for stunts (It is estimated the owners could have earned $500,000 a year from the thing just in rentals.), but shortly after a test flight the device disappeared. One owner sued the others for its return. In an ugly turn of events, before the lawsuit was settled, one of the men was beaten to death. The location of the belt is still unknown. Rocket Belt Kits So will my dream of flying a rocket pack ever come to pass? Even if the flight only lasted 21 seconds it would be a real thrill. Well, there still might be a chance if inventor Ky Michaelson has his way. Michaelson has been building rockets since 1951 (he bills himself as the Rocketman). I saw on the internet that Michaelson was engaged in a project to build a low-cost rocket belt that anybody could put together as a kit. Now, I was a bit suspicious, as there are dozens of inventors on the internet willing to sell you plans for stuff that really doesn't have much chance of actually working. A perfect example of this was seen on Discovery Channel's Mythbusters. (For those who haven't viewed this show, the co-hosts, Adam Savage and Jamie Hyneman, test the veracity of myths mostly by building various things and then blowing them up or otherwise demolishing them. Needless to say, the show is a big favorite here at the museum.) Episode 32 featured them getting plans for a personal flying machine off the internet for less than $100. The device they built used a pair of ducted fans powered by a small gasoline engine rather than a true jet engine. Despite spending ten-thousand dollars on the project, however, they were never able to get the rather impressive looking machine off the ground. If anybody is able to build a working rocket belt on a shoestring, however, it would be Ky Michaelson. Michaelson holds 72 State National and International speed records for rockets and founded C.S.X.T. (The Civilian Space Exploration Team) - the first group of amateurs to put a rocket into space. I contacted him by email and asked him how he decided to embark on this project. "I saw some information on the internet that said rocket belts cost $250,000 to build," he told me, "So I decided to prove that you could build a rocket belt for the cost of a motorcycle." Michaelson is pretty confident that he can make it work. "Hydrogen peroxide rocket motors are pretty simple. The problem is the control valve. That is the heart and the key to a successful flight. I was lucky to obtain a complete set of prints for the valve." If he can get it to work, he would like to see plans published so that anybody could give it a try. "If I can figure out how not to get sued, I will sell a kit," he told me. So, maybe I'll get a personal flying machine after all. I'll just save my money and avoid spending it on that new Harley. A rocket belt ought to be safer, anyway, right? Copyright Lee Krystek 2007. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|