Requiem

for a Planet: Pluto

|

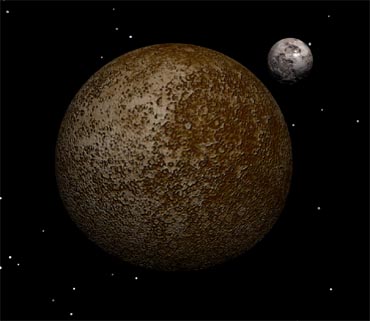

Artist

conception of Pluto and its moon Charon. (Copyright

Lee Krystek, 2012)

|

For almost three-quarters of a century schoolchildren

learned that our solar system had 9 planets: Mercury, Venus,

Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto. Then

in 2006 this changed, Pluto got demoted and now there are only

eight planets. What happened? Why did poor Pluto get kicked

out of the planetary club?

Wandering

Stars

To understand why Pluto isn't a planet, perhaps

it helps if we define what the term planet means. The

expression goes back to ancient times and comes from the Greek

word for "wandering star." Because the planets are bodies that

move in orbit around the sun, they do not stay in a fixed location

in the sky in relation to the stars. Ancient peoples, including

the Greeks, noticed that over a course of months these special

stars seemed to move along a particular path across the sky.

Usually it was in one direction, but occasionally they would

move backwards, then again forwards. The constellations (or

star groups) that they passed through were given special significance,

and today we know these as the zodiac.

It was clear to these early observers that the

wandering stars were different from the stationary ones, but

they didn't know exactly why. Back then the Greeks didn't have

telescopes and they were limited to using their naked eyes.

This meant they were only familiar with the most brilliant of

these wanders which they named for their gods. Today we are

aquainted with the Roman versions of these names: The brightest

was Jupiter, king of the gods, Saturn was his father, Venus

was the goddess of love, Mars, which appeared to be an angry

red, was the god of war, and Mercury was the messenger god.

|

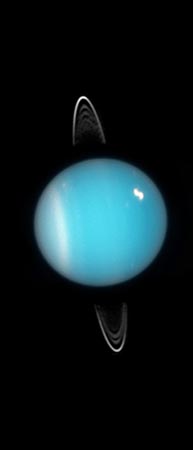

Uranus

was the first planet discovered in modern times, though

Herschel's telescope wasn't powerful enough for him to

see that it had rings. (NASA)

|

So in ancient times there were only six planets.

They weren't the only things that moved through the night sky,

however. Comets also progressed against the background of the

stars. Comets only appeared at very irregular intervals, though,

and they often had a long tail (comet actually means "hairy

star") so they were put into a different category than the planets.

New

Planets

Additional planets were not discovered until telescopes were

invented and the mechanics of how the solar system was arranged

- with the Earth orbiting around the sun, and not the reverse

- was understood. By the end of the 16th century Uranus had

been observed and recorded several times, but people who saw

it just thought it was a regular star or comet. In March of

1781 Sir William Herschel found it again and began to track

its motion. His first thought was that it was a comet, but

he and his fellow astronomers calculated that its orbit was

nearly circular around the sun and realized it was a planet

beyond Saturn. Herschel wanted to name it after the British

King, George III, but foreign astronomers disagreed and eventually

the name Uranus, god of the sky, was approved by consensus.

Surprisingly, Pluto was not the first member to be kicked

out of the planetary club. As far back as 1596, Johannes Kepler

had come to the conclusion that there was a gap between Mars

and Saturn large enough to accommodate another planet. The

discovery of Uranus further confirmed that there was a pattern

to how far planets were apart and that there was indeed an

empty space. In 1800 a number of astronomers started on an

intense search for such a planet in the gap. On January 1st,

1801, Italian scientist Giuseppe Piazzi found a small object

that was in a circular orbit in the right location. It was

declared a planet and named Ceres after the Roman god

of agriculture.

It soon became apparent, however, that Ceres,

with a diameter of 569 miles (960km), was much smaller than

the other planets. Within a year astronomers also realized it

was not alone. A large number of similar, but smaller, objects

were found orbiting in that region of space. Sir William Herschel

coined the term asteroids (which means "star-like") for such

bodies. Though there was no official organization at the time

to change the status of Ceres, within a few decades all references

to it being a planet disappeared from the textbooks. Today we

refer to the area in which Ceres and the other asteroids are

found as the "asteroid belt."

|

Ceres:

Got kicked out of the club too (NASA).

|

In 1846 the French scientist Urbain Le Verrier,

looking at the orbit of Uranus, came to the conclusion that

the way it moved suggested it was being pulled by the gravity

of an unknown body, probably another planet beyond Uranus's

orbit. He calculated where this planet could be found in the

sky and asked German astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle to search

for it with his telescope. Galle found it and it was dubbed

Neptune after the Roman god of the sea. In England John

Couch Adams had independently made the same calculations, but

couldn't find anybody with a telescope who would take him seriously

enough to do a search.

The

Search for the Ninth Planet

By the start of the 20th century scientists had

noticed the same type of unexplained motions in Neptune's orbit

that when seen in Uranus's orbit had led to Neptune's discovery.

Many astronomers began to suspect that there might be a 9th

planet out there somewhere. In 1906 Percival Lowell, a wealthy

Bostonian who had founded the Lowell Observatory, started a

search for it. When it still hadn't been found by his death

in 1916, the observatory hired an eager, 23-year-old astronomer

named Clyde Tombaugh to continue the search in 1929.

Tombaugh went at the tedious task tirelessly.

Each night he would photograph a section of the sky where the

planet was suspected to be. He then used a device called a blink

comparator, which allowed him to quickly switch back and forth

between pictures, to contrast that photo with one taken a few

weeks before. If any of the stars seemed to jump between the

two photos, he would know it was moving. This meant it was either

a comet or a planet.

|

A

young Clyde Tombaugh found Pluto (NASA)

|

On February 18, 1930, Tombaugh was looking at

a pair of photographs taken the month before when he saw such

a jump. Additional observations confirmed that the object appeared

to be in a near circular orbit around the sun and it seemed

that the 9th planet had finally been found.

The discovery was a world-wide sensation. Tombaugh

urged that a name be quickly selected. Some of the suggestions

included Zeus (the Greek name for the king of the gods) and

Percival, after the Lowell founder. Strangely enough, the name

Pluto came from an 11-year-old schoolgirl named Venetia

Burney who lived in Oxford, England. She had been studying the

Greek classics and thought that the name of the god of the underworld

would be perfect for such a cold and lifeless orb at the edge

of the solar system. Her grandfather, a retired Oxford librarian,

passed the idea onto a professor, who cabled the idea to the

Lowell. The name received a unanimous vote by the Lowell staff

and was announced on May 1, 1930. Its selection may have been

influenced by the first two letters being "PL" which were also

the initials of Percival Lowell.

The

Odd Planet

It wasn't long after Pluto's addition to the planetary

club that people began to notice that "one of these things was

not like the others." The first problem was its orbit. Further

careful studies showed that it wasn't as circular as had been

supposed. In fact, the orbit was so elliptical (like a squashed

circle) that it actually was closer than Neptune to the sun

for part of its year. Also, while the rest of the planets orbited

along a flat plane called the ecliptic, Pluto's orbit was tilted

off that plane by over 17°.

There was also the question of its size. Early

estimates made shortly after Pluto was found suggested it was

about the same diameter as Earth. However, as telescopes got

better and better it appeared that Pluto was smaller and smaller.

In 1978 astronomer James Christy found that Pluto had a moon

(later named Charon after a minion of the god Pluto in mythology)

and observation of its orbit allowed scientists to get a very

accurate measurement of Pluto's size: only 0.2% of the mass

of Earth.

|

The

telescope Tombaugh used in his search for Pluto. (Copyright

Lee Krystek, 2012)

|

Other discoveries appeared that caused some astronomers

to question Pluto's status. In 1992 scientists found evidence

that there was a large disc of scattered rocky and icy material

out beyond the orbit of Neptune. They dubbed this the "Kuiper

Belt" in honor of Gerard Kuiper who had speculated about such

a region back in the 1950's. Some scientists began to suggest

that rather than being a planet, Pluto was just the largest

member of this belt.

Planet

Eris

The matter came to a head in 2005 when astronomer

Mike Brown, working at the Palomar Observatory, discovered an

object far out beyond Neptune. It was eventually named Eris

(after the Greek goddess of strife - an apt name given all the

controversy it would cause). What was alarming about Eris was

that it appeared, with a diameter of 2,397km (1400 miles), that

it was just slightly bigger than Pluto. Should it be the tenth

planet?

The International Astronomical Union (IAU), which

was the group that had taken over the official naming of celestial

objects, was forced to confront the question the next year.

The IAU had three ways they could resolve the problem. Each

solution required them to develop an official definition of

the term planet, something that had never actually been done

before.

First, they could simply define a planet as an

object bigger than Pluto that orbited the sun in a roughly circular

orbit. This would make Eris the tenth planet. The downside of

this was that there were indications that Eris was not out there

alone. This meant that the ranks of the planets might rapidly

swell with these small, far-away objects.

|

Eris

as seen by the Hubble Telescope. (NASA)

|

The second thing they could do was to declare

objects like Eris and Pluto to be something other than planets.

This new class would include anything like them that was found

after this point in time.

There was a third possibility which was to keep

Pluto in the planetary club for historical reasons and place

Eris and other newly-found objects into a new class. Supporters

of this approach cited our commonly-held belief that the earth,

for reasons of history, has seven continents, even though it

is clear that under any logical definition Europe and Asia are

a single landmass.

The IAU decided on the second approach and defined

a planet as a body going around the sun, large enough to take

on a spherical shape and "clear the neighborhood around its

orbit" of other objects. Since Pluto shared its space with other

Kuiper Belt bodies, it failed this last test. A new class of

objects called dwarf planets was created and Pluto and Eris

were placed into this category.

Controversy

Not everybody was happy with the IAU's decision.

Astronomer Alan Stern, leader of NASA's New Horizon's mission

to Pluto, complained that the new definition was too vague and

inaccurate as many of the traditional planets have asteroid-type

objects orbiting near them so they have not "cleared their neighborhoods."

He also noted that only about 5% of professional astronomers

had been available to vote on the issue. However, Mike Brown,

who might have been credited with the discovery of a new planet

if the decision had gone another way, said that he thought that

the IAU had done the right thing. "There will be hundreds of

dwarf planets," Brown predicted.

The decision was probably made easier by Tombaugh's

death in 1997. Few members of the IAU would have wanted to strip

the eminent astronomer of his greatest success. His widow remarked,

however, that he would have accepted the change. She said Clyde

"was a scientist. He would understand they had a real problem

when they started finding several of these things flying around

the place."

|

A

picture of Pluto and Charon taken by the Hubble Telescope

(NASA)

|

As least a few political entities have come to

Pluto's defense because of their connection with Tombaugh. In

Illinois, where the astronomer was born, the state senate passed

a resolution saying that Pluto was "unfairly downgraded to a

'dwarf' planet." Similarly in New Mexico, where Tombaugh had

been a long-time resident, the House of Representatives passed

a resolution declaring that "Pluto will always be considered

a planet while in New Mexican skies."

For those that are sad about Pluto's fate, perhaps

it is best not to think of the planet getting as demotion, but

of having the honor of being a founding member of a whole new

class. The dwarf planets of our solar system now include Pluto

and Eris along with Haumea, Makemake, Sedna and Quaoar.

Even Ceres, which got kicked out of the planetary club

back in the 19th century, has been able to join this new group

(though it also retains its membership in the asteroid belt).

Will the definition of a planet change again?

Perhaps. Astronomers have spent the last 20 years searching

for planets circling stars other than the sun. As they find

more it's likely that we will find objects that don't quite

meet the current definition. Some change seems inevitable.

Is there still a 9th planet out there in our solar

system that might fit the IAU's new definition? In 1992 when

the Voyager 2 space probe flew by Neptune it got a chance to

get a better gauge on the planet's mass. This new information

showed that it was slightly smaller than originally thought.

When the planet's new size was used to recalculate its orbit,

the movements that suggested that there was a 9th planet tugging

on Neptune vanished. So it seems likely that the eight local

planets we are familar with are the only ones we have.

|

Meep

reacts to rumors that Pluto will be demoted in our comic

strip LGM.

|

A Partial Bibliography

Pluto Demoted: No Longer

a Planet in Highly Controversial Definition, by Robert Roy

Britt, Space.com, http://www.space.com/2791-pluto-demoted-longer-planet-highly-controversial-definition.html

The girl who named a planet

by Paul Rincon, BBC News, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/4596246.stm

Planet Quest: The Epic Discovery

of Alien Solar Systems, by Ken Croswell, The Free Press,

1997.

Discovering Pluto, Lowell

Observatory, http://www.lowell.edu/about_history_pluto.php

Copyright

2012 Lee Krystek. All Rights Reserved.