pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

Rogue Shark! The Jersey Shore Attacks of 1916 Part Two: The Hunt for the Killer Shark In twelve days in the summer of 1916 shark attacks along the New Jersey shore had left four dead and one maimed with the rogue shark still on the loose. On July 13, 1916, John Nichols, the ichthyologist from the American Museum of Natural History, arrived at Matawan, the site of the most recent attacks. After speaking to witnesses and examining the creek, he realized that the monster could not possibly be a killer whale as he'd speculated. Many witnesses had clearly identified the creature as a shark, lacking the spouting characteristic of a whale. What's more, the creek was much too small to allow the passage of a whale. Now Nichols was forced to agree that the attacker was indeed some kind of shark, probably a great white, and if it continued its northern drift up the Jersey coast it would soon reach the crowded beaches surrounding New York City. Nichols decided to start his own hunt for the killer shark. "My own belief is that this single fish has killed all four of the bathers and that if it is killed the attacks will end," he told the press. The Rogue Shark Theory In 1933 Dr. Sir Victor Coppleson, an Australian scientist, would coin a term for this type of killer fish. He would call it a "rogue shark." Like its land counterparts, the rogue lion or rogue tiger, this animal would ignore its regular prey and develop an unnatural, even an aberrant, taste for human flesh. Coppleson came to his conclusion by checking the dates and locations of shark attacks. "A rogue shark, if the theory is correct," he wrote, "and the evidence appears to prove it to the hilt - like the man-eating tiger, is a killer which, having experienced the deadly game sport of killing or mauling a human, goes in search of similar game. The theory is supported by the pattern and frequency of many attacks." Coppleson observed a beach might be free of shark attacks for decades, a cluster of them would occur, then the beach would again be free of attacks. He was convinced they would often stop after a single man-eating shark was captured. Though it was decades before Coppleson would publish his theory, Nichols' instincts told him that the Jersey shore attacks were the work of a single man-eater. Together with his friend, Robert Murphy, they equipped a boat for shark hunting and headed out into Jamaica Bay: The logical place, they thought, for the shark to show up if it continued its northern movement.

They were not alone in their quest. The shark attacks had struck terror into people along the coast. The number of bathers coming to the beach dropped in some places by 75%. Merchants that depended on tourism lost a quarter of a million dollars worth of business. Armed men in motorboats began to patrol the waters off the Jersey beaches. Communities began to offer a bounty for each shark caught and killed. There was even talk of having the military eradicate all sharks off the Jersey coast, though this was clearly impractical. The Big Game Hunter vs. the Great White Shark Two men who weren't planning on shark fishing were Michael Schleisser, a forty-year-old former lion tamer and big game hunter that was also one of the foremost taxidermists in the United States and his friend, John Murphy, a twenty-eight-year-old laborer for a steamship company. On July 14th, two days after the attacks in Matawan Creek, the two friends headed out in a small boat. As they boarded their dingy for a day of fishing in Raritan Bay, Schleisser noticed a broken oar lying discarded on the dock. The end with the paddle was missing. Picking it up, he threw it into the boat. "What do you need that for?" asked Murphy. "Oh, it'll come in handy for something," Schleisser replied. The two men started the engine on their eight-foot-long motorboat and headed out into the bay. At a spot just south of Staten Island, they let out a six-foot net to trawl the water. They continued for an hour until they were just four miles from the mouth of Matawan Creek. Suddenly the dingy slammed to a stop and the engine stalled. In fact, the boat was not just stopped, but was being towed backwards - and being pulled under the water by the net that had been let out of the stern. Schleisser looked out the back of the boat and saw a fish tail come out of the water. He recognized the creature as a shark. A big one. They were moving so fast now that the bow of the boat was rising into the air and the rear was taking on water. They had to do something fast. Murphy climbed into the front of the boat to get more weight on the bow, while Schleisser searched for a weapon. They had nothing but the fishing rods. They had never intended to hunt shark. No knives, no harpoons, no guns. Suddenly the shark's head rose out of the water and onto the stern of the boat. It was snapping its jaws and Schleisser realized that it intended to eat them. Men are not as safe in a boat from a shark as one might think. Sharks, especially great white sharks, have been known to attack boats to get at the people on board. With a strong snout butt a large shark can punch a hole in almost any small boat hull. In 1923 four miners were fishing off of New South Wales in Australia when a shark ripped a gaping hole in the bottom of their boat causing it to capsize. The shark ate one of the miners while the others watched. Suddenly Schleisser's eyes noticed the broken oar. Grabbing it he approached the shark's gaping jaws. He swung at the monster's head several times. Each time he missed as the shark's thrashing was rocking the boat wildly. Then Schleisser managed to get a hit on the creature's nose and another one on the gills. The monster, even more enraged than before, snapped at the hunter's arm. The jaws missed him, but the creature's head slashed across Schleisser's arm and the sandpaper-like skin tore open his wrist. The shark smelled blood and thrashed even more wildly. Then Schleisser got another lucky blow to the nose and that seemed to stun the creature. This was the opening that he needed and he followed that hit with strikes to the gills and head until the monster went slack. It was finally dead.

The men towed the shark back to the dock at South Amboy where volunteers helped the fishermen hoist the 350-pound creature from the water while Schleisser described to them "the hardest fight for life I've ever had." Schleisser took his prize back to his shop to mount it. When he opened the stomach he found fifteen pounds of flesh and bone. He shipped the bones to Dr. Frederic Lucas of the American Museum of Natural History, who was also Nichols' boss. He identified the remains as human. Nichols himself came to see the creature mounted at the front of Schleisser's shop. It was clearly a great white shark, Carcharodon carcharias. Though it seemed like a huge monster to those that looked at it through the window, it was only a two-year-old juvenile female that measured seven-and-one-half feet long. A full grown great white shark can measure over 20 feet long and weigh more than two tons. One Rogue or Many Killers? Was the Jersey shore killer this particular great white shark? The presence of human bones in the stomach certainly suggests that it might be the culprit. According to the rogue shark theory the creature may have been swept further north than normal and closer to shore. After its first hunting encounter with human beings was successful, it sought other opportunities. The rogue shark theory, however, has been out of vogue with many scientists for years. They argue that waves of shark attacks result from environmental conditions (for example changes in water temperature) being favorable for attacks, not because of the habits of an individual shark. The Jersey shore attacks, despite earlier perceptions, could have actually been several different sharks. In fact, many scientists also doubt that the creature responsible for the attacks in the Matawan Creek could be a great white shark. A great white would be extremely uncomfortable in such a narrow, brackish channel of water. Its body would begin to lose salt into the fresh water and it would soon become sick and weak. A more likely candidate, they argue, would be the bull shark. The bull shark is comfortable in fresh water and can even live in lakes. They are known to live off the coast of New Jersey and are also man-eaters.

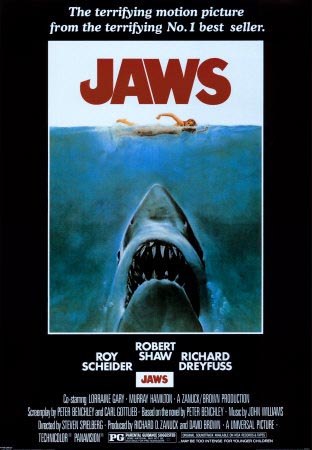

Still, one thing is for certain: once Schleisser caught his great white shark the attacks ceased. The story of the Jersey shore attacks, though forgotten by many; still has a place in the public mind. The well-known fictional book Jaws (written by Peter Benchley) and the blockbuster 1975 movie of the same name directed by Steven Spielberg draw heavily from this history. Benchley took many of the details - including the final battle with the shark trying to climb into the boat - and included them in his book. With literary license, however, he moved the location to a small New England seaside town and made his shark 25 feet long. The impact of these events in 1916 made scientists rethink what they thought they knew about sharks. No longer were they creatures thought to be too weak or timid to confront humans. Man learned the hard way that when it comes to the sea, he can just as well be the prey as the predator. Copyright Lee Krystek 2009. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|