pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

The Mystery of the Rosetta Stone - Part I:

The Unreadable Script The young French soldier was hot, thirsty and tired. He had been involved in Napoleon's Egyptian expedition for months. He'd marched through the desert with no water, chasing after strange pools of liquid that miraculously appeared on the horizon, and then cruelly disappeared as he approached them. He'd also choked on storms of dust that raced across the landscape. Now he and his companions had been assigned to tear down an ancient wall so they could build an extension to Fort Julien. Backbreaking work. As he pried another stone out of the wall, its color struck him as being odd. It was dark, almost black actually. On one side that was flat there appeared to be writing of some sort. Not French, to be sure, but some strange script. No, not just one type either, but three different types. Very odd. He decided to call over the officer-in-charge over to take a look at it. What that young, unnamed soldier had done was to discover the Rosetta Stone - an unremarkable chunk of black rock, covered with seemingly indecipherable markings - that would solve one of the greatest linguistic mysteries of the 19th century: how to read the ancient writing left by the Egyptians thousands of years ago. Napoleon and the Rosetta Stone On May 19, 1798, General Napoleon Bonaparte set sail with the French fleet for North Africa. The French were at war with the British and by invading Egypt, Napoleon hoped to disrupt England's trade with its colony of India as well as create a base from which he could make advances into the sub-continent. Although the expedition was primarily military in nature, Napoleon decided to take with him some 167 scientists and scholars to document every aspect of the country's geography, economy and history with an eye to possibly turning it into a colony. The scientists were at first very disappointed in what they found: squalid cities that bore no resemblance to those mentioned in classical history. This, coupled with the harsh conditions (heat, little water and poor food), discouraged them.

As some of the scholars traveling with the army penetrated past the coastline and up the Nile River, though, they began to run into mind-boggling remnants of the ancient Egyptian culture. The ancient structures at Dendera, Kom Ombo, Edfu, Esna and Thebes fascinated them. They were gigantic in size and covered with thousands of mysterious symbols that nobody could understand. Even the soldiers were impressed. After seeing the great temple at Dendera one commented, "Since I came to Egypt, fooled by everything, I have been constantly depressed and ill: Dendera has cured me; what I saw today has repaid me for all my weariness; whatever may happen to me during the rest of this expedition, I shall congratulate myself all my life for having been part of it." One scholar, Dominique Vivant Denon, took to sketching everything he saw but was overwhelmed by trying to record the hieroglyphs. "It would take months to read them," he wrote, "supposing the language was known: it would take years to copy them." Whatever the scholars examined, were covered with these mysterious symbols that they could not read. It became obvious that the key to understanding Egypt was understanding this strange writing. A Dead Script

The French were not the first to visit Egypt and puzzle over these strange symbols. As far as anyone knows, the last time Egyptian hieroglyphs were chiseled into stone was August of 394 AD. Over the next 1,528 years, the ability to read this ancient script vanished. When Greek scholars visited Egypt in the seventh century AD, they saw the picture writing and called them "sacred carvings" which in Greek is the word "hieroglyphs." No Egyptian alive at that time could read them as the ancient language had been replaced first by Coptic, used by Egyptian Christians and later, after the Arabs conquered Egypt in 642 AD, by Arabic. One of the scholars, a priest named Horapollo, published a book on the writing called Hieroglyphika. He argued in it that unlike other western languages, which are phonetically based (that is each symbol stands for a sound) each Egyptian hieroglyph stood for an idea, or sometimes one of several ideas. "When they mean a mother, a sight, or boundaries or foreknowledge they draw a vulture. A mother, since there is no male in this species of animal" [of course, Horapollo is completely incorrect in this statement] "It stands for sight since of all animals the vulture has the sharpest vision. It means boundaries because when war is about to break out, the vulture limits the place in which it will be fought by hovering over the area for seven days and it stands for foreknowledge because, in flying over the battlefield, the vulture looks forward to the corpses the slaughter will provide." Horapallo based his conclusion that each hieroglyph stood for one or more ideas on little or faulty evidence. Because of this, his book would hinder the understanding of the Egyptian writing for almost a thousand years. In the 18th century the French Scholar C.J. de Guignes advanced the theory that the oval outlines (which he called cartridges, or in French, cartouche) which contained several hieroglyphs were probably meant to draw attention to important names, like that of a pharaoh. His guess was right, but some of his other ideas were just as equally wrong. Since de Guignes agreed with Horapallo that hieroglyphics was a form of picture writing, he theorized it was related to Chinese. In fact,

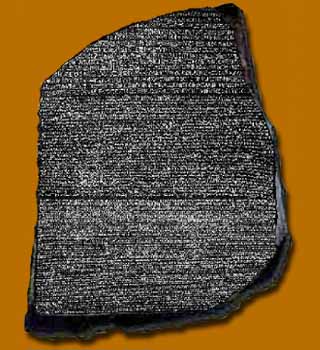

he suggested that the Egyptians must have colonized China in ancient times, an idea that turned out to be totally erroneous. Finding the Stone Scientists puzzled over the riddle of hieroglyphics with seemingly no real answer in sight until July of 1799. Napoleon's forces were still trying to take control of Egypt and to this end a company of soldiers was assigned to clear an area next to Fort Julien at a place called Rosetta, located about 35 miles north of Alexandria, in preparation for building an extension to the fort. According to one version of the story, embedded in an old wall they found a black stone with a message engraved in three different languages. Almost immediately the officer with the company, Pierre Francois Xavier Bouchard, realized that this could be an important archeological find. The stone was soon sent to the Institute of Egypt in Cairo to be examined by Napoleon's scholars. They became very excited. The rock, which was thereafter referred to as the "Rosetta Stone," apparently had the same message written on it in three different scripts: At the very top were fourteen lines of hieroglyphs, then just below that thirty-two lines of another Egyptian script that had become known as "demotic," and finally fifty-four lines written in Greek. Neither of the Egyptian scripts could be read, but most of the scholars had learned Greek in school so it was easily translated. The message was a proclamation from some priests saying that in return for giving them money they would be building statues of Egypt's then current ruler, Ptolemy V, in all their temples and that they would worship the statue three times a day. At the time the slab of rock (or stela) bearing the message was erected, Egypt was ruled by Greeks, so it was logical to write the proclamation in multiple languages in order to be read by both Egyptians and Greeks. Although the stone was broken on the top and right side and none of the scripts carried the complete message, the scholars expected the stone would soon help unravel the mystery of the hieroglyphics that had troubled them so.

Before they could do much with the stone it was first apparent to the French scholars that they needed to get it out of Egypt and back to France. The war in Africa had turned against the French and Napoleon had left the continent to attend to political problems in Paris. By spring, 1801, the French Army with the scientists and their collections (including the Rosetta Stone) were forced to retreat to Alexandria. They were soon besieged by the British and forced to surrender in September. As part of the surrender agreement the scholars were forced to hand over their collections. General Menou, who was in charge, tried to retain the stone, claiming it as personal property, but was finally forced to turn it over to the British. The Rosetta Stone was already considered so valuable that the French officer in charge of handing it over to the British recommended that they take the Stone and leave the city immediately before French troops realized what was happening. Colonel Turner of the British army immediately took it with him on board the HMS L'Egyptienne arriving at Portsmouth, England, in February of 1802. So, if the war had just gone a bit differently, the Rosetta Stone would might have found a permanent home in the Louve in Paris, rather than were it sits today in the British Museum in London. In either case, scholars in Europe now figured they had everything they needed to finally solve the mysterious meanings behind hieroglyphics. They were wrong. The one thing they lacked was a genius. Many bright men attacked the problem of the Rosetta Stone only to fail. One described the problem as "too complicated - scientifically insoluble!" It would not be until 1822, almost a quarter of a century after it had been found, that the secrets of the Stone would finally be unlocked. Part II: The Race to Decipher the Code Copyright Lee Krystek 2006. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|