pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

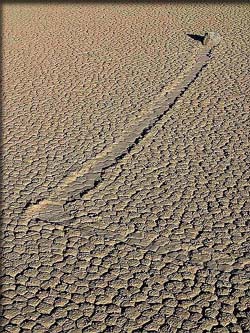

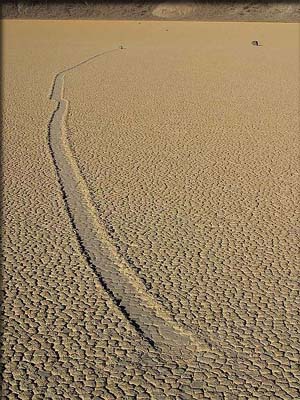

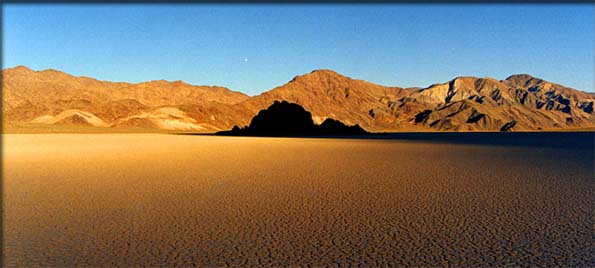

The Strange Sailing Stones of Death Valley

In this mysterious and desolate corner of the California desert, the stones move by themselves. There is no doubt that California's Death Valley National Park is an unusual place. Situated in the Mojave Desert, it is the driest location in North America. With one spot at 282 feet (86 m) below sea level, it also has the distinction of being the lowest elevation of any place on the continent. Finally, it also known to be the hottest locale on Earth with temperatures hitting a record high of 134 °F (56.7 °C) in the Furnace Creek section of the park. While all these features are certainly unusual, there is one more oddity about Death Valley that makes it one of the strangest places in the world. It's a place where the rocks move by themselves. Now you might argue that there are plenty of places where rocks move without human or animal intervention. During an avalanche, tons of mud, soil and rocks can come tumbling down steep slopes. And during an earthquake, even large boulders can go bouncing around. In Death Valley, however, these stones slide across a nearly-flat, dry, lakebed called Racetrack Playa leaving long, smooth tracks. No avalanches or earthquakes needed. Not just little stones either. Some of the moving rocks are estimated to weigh as much as 700 pounds (318 kilograms). What's even stranger is that some rocks seem to move in long straight lines, then suddenly change directions. Others look like they've taken a smooth, curved path. Some of the tracks made by the stones are just a couple of yards long, while others run hundreds of feet.

The lakebed is very isolated and rarely visited by people. Nobody has ever been there at the right time to actually see a rock in motion. Because of this, over the years a number of odd theories have been developed about what might be behind the phenomenon. Some of the ideas include magnetism, mysterious energy fields and even pranksters. Some of the more extreme solutions involve flying saucers and aliens. Scientists Take an Interest The strange phenomenon was first documented in 1915 when a prospector named Joseph Crook from Fallon, Nevada, visited the area. Crook observed that some of the stones sitting on the lakebed were at the end of long "tracks," giving the impression that they must have moved, scraping up a little less than an inch or so of the soil as they crept along. In 1948 two geologists, Jim McAllister and Allen Agnew, published the first scientific report of the phenomenon in the Geologic Society of America Bulletin. The two suspected that high winds and wet, slick mud on the lakebed might be behind the odd movements. It also occurred to them that if the effect was due to conditions on the valley floor, they might find rocks that do the same thing in other locations. A similar phenomenon was found to be happening at Little Bonnie Claire Playa in Nye County, Nevada, and later on at Great Slave Lake, in Canada's Northwest Territory. In 1955 George M. Stanley looked into the mystery. He thought that the stones were too heavy to be moved by the wind alone. He suggested that at times the dry lakebed would flood and if temperatures were low enough, the water would turn to ice. As these ice sheets moved, they would carry the rocks they trapped along with them. Corralling the Stones It wasn't until 1972, however, that somebody decided to test Stanley's theory. Researchers Bob Sharp and Dwight Carey went to the valley and picked thirty stones for their test which looked like they had moved in the recent past. They gave each of the stones names and placed stakes in the ground near them to mark their current locations. They then picked a few special stones and created a corral around them using metal stakes made of rebar. The idea was that if a large ice sheet was involved in moving the stones, they would be blocked or deflected by the stakes of the corral. The stones seem to take no notice of the corral, however, and one of them left it that winter only narrowly missing one of the stakes on its way out. This seemed to indicate that if ice was involved, it was just a small collar of ice around the stone itself, not a large sheet. One of the other things that came out of the seven year study was the observation that none of the stones seemed to move in the summer. Only during the winter.

During the study 28 of the 30 stones originally selected for monitoring moved. The smallest stone (named Nancy) which was only a few inches across, moved the longest distance: 860 feet (260 m). The largest stone to move weighed about 80 pounds. One of the heaviest stones, Karen, which was estimated to weigh 700 pounds, did not move at all. However, after the test period was over, Karen disappeared. It was rediscovered by San Jose geologist Paula Messina in 1996 about a half mile from its last known location. In 1995 another scientist, Professor John Reid, and several of his students went to Racetrack Playa to examine the mystery. They found evidence that despite the research done in the seventies at least some of the stones were moving due to being embedded in a large sheet of ice (up to half a mile wide). They based their conclusions on the marks found on the ground after the winter of 1992-1993. However, there is confirmation that the stones can also move individually. In 2011 a study suggested that the dry lakebed can flood, then freeze. As the water thaws, ice may cling to the stones, floating them like little icebergs. Partly floating in the water with ice to reduce the friction, a strong gust of wind can get even a very heavy stone moving. Once a stone is on the move, the energy it needs to keep going is only half of what is needed to get started, so they can continue for quite a distance even if the wind gust drops. The Tabletop Experiment In 2006 Ralph Lorenz, a NASA scientist, developed a tabletop experiment that seemed to confirm the idea of "ice rafts" floating and moving the stones. He was first drawn to the sailing stone mystery because he was interested in meteorological conditions on Saturn's moon of Titan and Racetrack Playa seemed to have some very similar characteristics. Lorenz put a rock into a Tupperware container and then filled the container with water until the rock was almost covered. He then froze it and let it thaw out a bit until there was just a small raft of ice with the rock caught in it. He then put the rock with its "ice raft" into a tray of water with sand at the bottom. The ice floated the rock so that it only lightly sat on the bottom. Lorenz could then blow on the rock and it would move easily across the sand, leaving a trail behind it. Scientists would like to confirm the stones' movements by the use of inexpensive time-lapse digital cameras, but so far it's a difficult task to catch the rocks in the act. It is believed that a single stone might not move for years and when it does, the movement might only last about 10 seconds. Thus though there seems to be a logical mechanism for the movements of the stones, nobody has actually ever seen it happen. So we still can't disprove that it isn't just the result of a group of extraterrestrials out to play a prank on us humans after all.

Copyright Lee Krystek 2014. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|