|

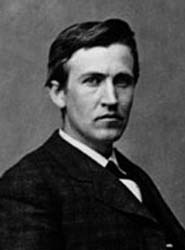

Nikola

Tesla at age thirty-seven.

|

Sorcerer

of Lightning: Nikola Tesla

He is a mysterious, almost forgotten, figure, but his

inventions in the areas of electrical motors, electrical distribution,

remote control, low and high frequency waves, radio, radar and

even death rays continue to have a major impact on science and

engineering today. He was years and even decades more advanced

than his colleagues and many argue he took to his grave knowledge

that we still struggle to discover today.

Part One: So

Many Inventions, so Little Time

It was a summer night in 1899 when Nikola Tesla,

perhaps the greatest electrical genius of his time, emerged

from his Colorado Springs laboratory to observe the first major

test of what he would later call "my greatest invention."

From outside the square barn-like building he could see a wooden

tower eighty feet in height from which a 142-foot metal mast

emerged. At the very top of the mast was a three-foot copper

ball.

An earlier test, lasting only one second, had

confirmed that the equipment in the building, an enormous "tesla

coil" and the tower seemed to work. Now would come the

full test. Neither Tesla nor his assistant was exactly sure

what would happen - giant sparks? fire? explosion? - but they

were ready to take the risk. Others had been warned: Outside

the laboratory grounds were signs posted "KEEP OUT - GREAT

DANGER" and over the door of the building was a quote from

Dante's Inferno: "Abandon hope all ye who enter here."

When Tesla was ready, he shouted to his assistant,

Czito, "Now! Close the switch!" Czito had been instructed

to keep the machine running until Tesla told him to turn it

off. Inside the building the massive switch was thrown and outside

fireworks started to take place.

A heavy current raced through the primary coil

of the machine and lightning bolts started to explode from the

mast. Tesla watched as giant electrical sparks 135-feet long

jumped from the large copper ball. They generated a thunder

that could be heard 15 miles away. Tesla was so enthralled with

the display that he lost all track of time.

Suddenly the lightning stopped. Teslas snapped

out of his trance and raced into the building yelling, "Why

did you do that? I did not tell you to open the switch. Close

it again quickly!"

His assistant shook his head. He hadn't turned

off the current. The power company was no longer sending it.

A quick call to the power station revealed the

trouble. In the one minute it had been operating, Tesla's machine

had overloaded the powerhouse generator, setting it on fire.

The town of Colorado Springs was in a blackout and Tesla himself

would have to take a team of trained workmen to the station

to fix the dynamo. Even so, Tesla knew his new invention, his

"resonate transformer," really worked.

Early

Life

Nikola Tesla was born in 1856 in a mountainous

area of the Balkan Peninsula that was then part of the Austro-Hungarian

Empire. His parents were Serbian. His father, an Orthodox priest,

was a writer and poet. His mother had mechanical aptitude and

invented many appliances to use around the household and farm,

including an eggbeater.

Tesla was such a brilliant mathematician in school

that he performed integral calculus in his head, a skill that

left his teachers thinking he must be cheating. While still

at school he decided he wanted to become an engineer. This was

a career which conflicted with his father's desire for Tesla

to follow him into the priesthood. In the end, Tesla won the

battle and was enrolled in the Austrian Polytechnic School at

Graz.

While studying electrical and mechanical engineering

Tesla was shown the newly-invented Gramme dynamo that could

be used both as a electrical motor and a generator. He studied

it and observed to his teacher that there should be some way

of doing away with the inefficient sparking connector on the

device. His professor was skeptical, but Tesla was right. Over

the next few years Tesla would come up with the idea of alternating

the current flow (known as AC) to solve this problem. In the

end, this idea would underlie the design of every commercial

electrical system throughout the world.

Tesla was hired by firms in Germany and France

to improve their direct current (DC) generation facilities,

but neither was interested in his radical AC designs. It became

apparent to him that he would have to take his inspiration to

someone who could really appreciate it. To the greatest electrical

engineer of the day, the renowned "Wizard of Menlo Park,"

Thomas Alva Edison.

After getting a letter of introduction from one

of Edison's European business partners, Charles Batchelor, Tesla

took a ship to New York City. At the age of 28 he was off to

see the Wizard.

Tesla and Edison

Arriving at Edison's office Tesla presented him

with the letter of introduction from Batchelor. In part it read:

My Dear Edison, I know two great men and you

are one of them. The other is this young man!

|

Thomas

Alva Edison

|

Testla proceeded to explain his work and his idea

for alternating current. Edison wasn't interested. Edison already

had an enormous amount of money invested in his own DC system

and didn't want to change. He did recognize that this young

man from Europe was very talented and offered to hire him, promising

him $50,000 if he could make certain improvements in his DC

generation plants.

Despite both being genius inventors, Tesla and

Edison had very different styles. Edison was largely self-taught,

while Tesla had a formal European education. Edison discovered

by trial and error, a method he expressed best in his famous

saying, "Invention is five percent inspiration and 95 percent

perspiration." Tesla preferred to think about an invention

and would only build the actual model when he had it all worked

out in his mind. Tesla's thinking was so precise that the first

model would almost always work the way he expected with no alterations.

Tesla once said of Edison:

If Edison had a needle to find in a haystack,

he would proceed at once with the diligence of the bee to examine

straw after straw until he found the object of his search..

I was a sorry witness of such doings, knowing that a little

theory and calculation would have saved him ninety per cent

of his labor.

It wouldn't be long before the men would clash.

Just a few months after starting, Tesla finished his improvements

and went to Edison to get his $50,000. Edison, who probably

thought that what he had sent Tesla to do an impossible job,

refused to pay, saying that the offer had not been meant to

have been taken seriously. "When you become a full-fledged American,

you will appreciate an American joke," Edison quipped.

Disgusted, Testla resigned and soon got involved

with investors who wished to build an improved arc lamp. They

founded the Tesla Electric Light Company. His design

was a success, but all the money went to the investors. Tesla

was soon looking for another opportunity.

It came in the form of A.K. Brown of the Western

Union Company. Brown agreed to invest in Tesla's idea for an

AC motor. In a small laboratory not far from Edison's office,

Tesla developed all the components necessary for an AC generation

and distribution system along with his AC motor. Late in 1887

Tesla filed for seven U.S. patents on his AC systems. The inventions

were so unique that they were issued without a successful challenge.

The

War of the Currents

George Westinghouse, inventor of railroad air

brakes, heard about Tesla's system and visited him at his laboratory.

After viewing the inventions, Westinghouse paid $60,000 for

the patents, which included $5,000 in cash and 150 shares of

stock in the Westinghouse Corporation. Westinghouse then used

Tesla's AC system to challenge Edison's DC system for the future

of electrical distribution within the United States.

|

Artist

conception of Teslas' resonant transformer in action.

|

The AC system was clearly superior. In order to

send electricity any distance, it must be at very high voltages.

The voltage in an AC system could be stepped up or down to different

voltages very easily with a device called a transformer. Transformers

were not available for DC at that time, which meant that DC

power couldn't be sent more than a few blocks because lower

voltages needed to be used in homes. A DC system like Edison's

might require a power plant within a few blocks of every house,

instead of a single power plant for the whole city.

Edison, ignoring this, started a full scale propaganda

campaign against Westinghouse, Tesla and AC current. He hired

a man by the name of Harold Brown to go around the country and

demonstrate how AC was more dangerous than DC (something that

wasn't necessarily true) by staging shows where he electrocuted

dogs and old horses. Brown referred to this process as being

"Westinghoused." Brown even managed to buy a used

Westinghouse generator and get it hooked up to the world's first

electric chair at New York's Auburn State Prison so that AC

would be associated with electrical executions.

Despite the smear tactics employed by Edison,

it became clear that the AC system had many advantages. In 1892

the Chicago World's Fair was lit entirely with AC power coming

from twelve thousand-horsepower AC generation units located

in the fair's Hall of Machinery. Competitors had bid a DC system

for the fair, but lost the job because the huge amount of copper

needed for such a DC system (because of its low effiencey) was

too high.

As Westinghouse started winning the war, Edison

was forced to merge his company with the newly formed General

Electric Corporation. General Electric would have taken control

of Westinghouse too if it hadn't been for the generosity of

Tesla. Tesla gave up control of AC patents worth millions of

dollars because he believed that an independent Westinghouse

Company was the only way his AC system would be widely adopted.

This move by Tesla ensured the future of AC, but

left him short of cash to pursue his research in the future.

Taming

Niagara Falls

As a boy Tesla had seen an engraving of the great

falls of the Niagara river and dreamed of harnessing their power.

In 1893 he actually got his chance. Lord Kelvin, the head of

the commission in charge of a project to tap power from the

falls, originally had argued against Tesla's AC system, but

changed his mind after visiting the Chicago World's Fair. Impressed,

Kelvin supported AC for the project and Westinghouse won a contract

to build a powerhouse at the falls.

|

Tesla

dreamed of taming the power of Niagara Falls.

|

Tesla designed the systems and was confident they

would work, though a project of this magnitude had never before

been done. Investors, including J.P Morgan, were nervous about

the success of the venture. The project was difficult, expensive

and took five years to complete. On November 16, 1896, when

the switch was thrown, Tesla's systems worked perfectly. One

by one each of the ten planned generators came online over a

few months. The Niagara power station generated some 15,000

horsepower of electricity, a phenomenal amount for the time.

Newspaper and engineering journals agreed that,

as the New York Times put it, Tesla deserved the "undisputed

honor" of making the project possible. Lord Kelvin said

Tesla had "contributed more to electrical science than

any man up to his time."

Experimenting

with High Frequency

Back at his laboratory in New York City, Tesla

started to look into what happened with electricity when you

alternated it at extremely high frequencies. At first he tried

altering one of his AC generators to do this, but the machine

flew apart when it reached twenty thousand cycles (alterations)

per second. To go further he had to invent a new device. Dubbed

the "Tesla coil," it could take normal household current

(60 cycles a second) and step it up to thousands of cycles per

second. The coil could also generate extremely high voltages.

Testla thought that high frequency electricity

would have many advantages: Lamps would give out more light,

electricity would travel more efficiently through wires, and

systems would be safer because high frequency electricity passed

across the surface of a person's body rather than through it.

Using this technology, Tesla tried to make better

and brighter lamps than the incandescent bulbs Edison had marketed

so successfully. In incandescent lamps, only about 10 percent

of the energy it uses comes out as light. Tesla hoped he could

find a better solution. His work resulted in the first neon

and fluorescent lights ever made. It was during this phase of

his experimentation that he discovered that he could make a

lamp light with no wires attached to it at all just by using

high frequency electricity that would pass through air. The

effect would eventually be known as radio transmission.

By using a Tesla coil tuned to the same frequency

as another Tesla coil sending energy, Tesla realized that he

could send signal through thin air. He was about to demonstrate

this in 1895 by sending a signal 50 miles to West Point, New

York, when his lab caught fire and burned down. For this reason

he didn't get to file a patent on the system until 1897. Unfortunately,

an Italian inventor, Guglielmo Marconi, had filed a patent in

England in 1896 for a less capable system. As Marconi worked,

at first Tesla was unconcerned about his progress saying, "Marconi

is a good fellow. Let him continue. He is using seventeen of

my patents", but later a fight broke out between the inventors

over who had first invented radio. The fight would became particularly

bitter when Marconi won the Nobel prize for the invention in

1911. Marconi's first American patent application, made in 1900,

was denied because of Tesla's earlier patent, but later the

U.S. patent office reversed its decision, giving a patent to

Marconi. It wasn't until 1945, two years after Tesla's death,

that American courts upheld Tesla's patent and his claim to

the invention of radio.

Robotic

Boat

From radio signals it was only a short hop in

Tesla's agile mind to radio remote controls. In 1898 at an electrical

exhibition in Madison Square Garden, Tesla had a small indoor

pond built and into this pond he placed a strange iron-hulled

boat that looked like a small bathtub with a lid. By using radio

signals, Tesla was able to control the boat's motor, sending

it zipping around the pond seemingly under its own control.

He even installed lights on it he could blink at a distance

from his control box. Many observers, unfamiliar with radio

waves, thought that the device must have a brain of its own

or that somehow Tesla was controlling it with his mind. When

it was first shown "it created a sensation such as no other

invention of mine has ever produced," Tesla would later write.

Tesla called the object a "teleautomaton"

and thought of it as the first of many robotic inventions that

would serve mankind. When a reporter suggested that such a boat

might be made to carry an explosive charge and used as a weapon

of war, Tesla grew angry. "You do not see there a wireless

torpedo, you see there the first of a race of robots, mechanical

men which will do the laborious work of the human race."

Wireless

Power

|

Tesla

sits in his laboratory while his lightning strikes around

him in this trick photograph.

|

Tesla's experiments with radio convinced him it

was possible to send not only electrical signals through the

air, but power. Conditions for this would be best at high altitudes

where the air was thin. Knowing this, Tesla's patent lawyer

and friend Leonard E. Curtis, suggested that Tesla might set

up a new laboratory near mile-high Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Curtis owned part of the El Paso Power Company located there

and could get him free electricity for his experiments.

Tesla spent a year at the site in Colorado testing

and experimenting with his "resonate transformer."

The results convinced him it was possible to send power through

the air. In the spring of 1900 he packed up his Colorado laboratory

and returned to the East coast, determined to bring the world

a new way to get electrical power.

To be continued in part two: Power

Through the Air

Copyright Lee

Krystek 2002. All Rights Reserved.