The

Truth about Truth Serums

A

staple of old spy films, can you actually inject somebody with

a drug that will make them reliably spill the beans to you?

A

staple of old spy films, can you actually inject somebody with

a drug that will make them reliably spill the beans to you?

The

modern idea of a drug that could ensure someone is telling the

truth originated with a doctor named Robert House in 1916. House

was an obstetrician that practiced in a small town called Ferris

just outside of Dallas, Texas. While delivering a baby on September

7 of that year, he injected the mother with scopolamine

as a pain killer putting her into a state of "twilight sleep."

After the baby was born House asked the father if he had a small

set of scales to weigh the baby, but the father didn't know

where they were located. His wife, apparently still asleep,

however, spoke up and said, 'They are in the kitchen on a nail

behind the picture." (Which they were).

The

wife, when she awoke, neither remembered the incident nor any

of the pain associated with the delivery. It occurred to House

that somehow the drug had shut down the higher levels of the

brain while leaving her mind still able to answer simple questions.

As he experimented with it he became convinced that the answers

given under scopolamine where always completely truthful and

the drug could be used for forensic inquiries.

House

wasn't the first person to notice that certain substances affected

the brain and elicited truthful answers. The Roman natural philosopher

Pliny the Elder supposedly said, In vino veritas which

translates to "in wine there is truth" after observing the how

intoxicated people often speak what's in their mind without

regard to the consequences.

|

Pliny

the Elder felt that wine would get at the truth.

|

House

thought scopolamine, however, would be a lot more reliable in

eliciting truth than a bottle of Burgundy and went on a campaign

to see it adopted as a standard law-enforcement tool.

To his

credit, House wasn't as interested in convicting people of crimes

with the drug as he was at proving their innocence. In a least

one experiment House was able to show that the subject in question,

a man named Scrivener, while under influence of the drug, denied

being involved in a robbery for which he was being prosecuted.

Later it was shown that Scrivener was indeed in another city

at the time of the crime (in police custody), just like he had

said under the influence of the drug.

House

became an enthusiastic proponent of the drug's use and in the

years following his observations police departments experimented

with scopolamine and other similar drugs (scopolamine itself

had a number of undesireable side effects that limited its use).

One of the other popular substances used for this purpose was

sodium thiopental (marketed under the brand name Sodium

Pentothal).

Sodium

Pentothal

Sodium

Pentothal is member of a class of drugs called "barbiturates"

that depress the nervous system (similar to the effects of alcohol).

It tends to decrease inhibitions and slow creative thinking,

making it harder to come up with and remember lies. While it

is popular to refer to any of these drugs as truth serums neither

scopolamine nor Sodium Pentothal is a serum. The use of the

word is a misnomer as serums are derived from animal blood and

used mainly for inoculations against diseases.

In 1963

the United States Supreme court ruled that confessions that

came as a result drugs were "unconstitutionally coerced" and

couldn't be used in court. In addition, experts had come to

the conclusion that things said under the influence of the drugs

were also unreliable. They might be the truth, they might be

a fantasy or they might be the result of the drugged person

just trying to please the questioner.

|

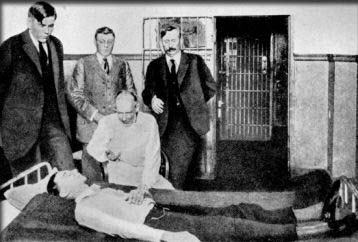

Dr.

Robert House injects an inmate in prison in an experiment

to find the truth.

|

This

made the truth serums of limited interest to the law enforcement

community. However, they did have some medical use to psychiatrics

as they could be administered to patients who had been through

a trauma and they seemed to assist them in talking about their

experience. This, in turn, made the patients feel better and

it didn't really matter if what they were saying was the objective

truth or only something that they believed.

The

CIA and Mind Control

Even

though law enforcement lost interest in truth serums as any

evidence they uncovered could not be used in court, intelligence

agencies still found them interesting. The information the spy

agencies needed wasn't necessarily something that would useful

in a court room.

In fact,

starting right after World War II the CIA conducted a program

designed not just to produce a drug that would force a subject

to answer truthfully, but also to control a person's mind and

get them to do things they would not normally have done.

The

program, best known as MKUltra, ran from about 1950 through

the early 1970's under various names. Much of what was done

turned out to be illegal and unethical. A favorite drug of choice

by these experiments was Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD).

LSD is a powerful agent that causes visual hallucinations and

illusions (colloquially known as "trips"). It is odorless and

tasteless and the effect can last for as long as 12 hours.

Experiments

with the drug showed it was too unpredictable to be used as

a truth drug, but the CIA thought it might have other uses (for

example, slipping it to a unsuspecting person about to give

an important speech in an attempt to discredit them). For this

reason the agency experimented by giving "surprise" trips to

unsuspecting personal. Unfortunately this caused one subject,

an Army doctor named Frank Olson, to go into a deep depression

and leap from a 13 story building.

|

Report

into the CIA's illegal activites with LSD and other drugs.

|

The

CIA also tried using a combination barbiturates (known as a

"downers") injected into one arm and an amphetamine (an "upper")

injected in the other. The effect was to cause the person to

babble without control. In this state the interrogator could

then attempt to ask questions and get answers.

In 1973

the CIA became fearful of their illegal work being exposed and

the director at the time, Richard Helms, ordered all MKUltra

files destroyed, so many details of the project are unknown

even today.

BBC

Experiment

So do

truth serums really work? In 2014 BBC correspondent Michael

Mosley, as part of a series on drugs, decided to find out. Under

the care of anesthetist Dr. Austin Leach, Mosley was given a

low dose of Sodium thiopental. When asked what his profession

was he was able to tell his questioner that he was a heart surgeon

instead of a journalist and even make up a supporting story

about the last operation he had performed.

When

the dose was increased, however, and the question repeated he

cheerful volunteered that he was a television producer. Later

on, when asked why he didn't lie, he answered "because the thought

of lying never occurred to me." So drugs designed to elect the

truth can work. The main problem, besides being inadmissible

in court, is that they can work too well, and the subject might

not just start babbling the truth to the interrogator, but also

falsehoods designed not designed to fool the questioner, but

to please them.

However,

there a clearly agencies and organizations that would love to

find a reliable truth serum and with our ever increasing repertor

of medications and a growing understanding of how the brain

works, it may not be too long before such a drug exists. They

question is under what circumstances would it be ethical to

use it?

Copyright Lee Krystek

2017. All Rights Reserved.