pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

Amazing Mazes They can be as simple as a game in a child's coloring book, or as enveloping as a house of mirrors. They can be entertainment for a Sunday afternoon stroll in a garden or a path along a deep spiritual journey. They are mazes. How do we define the word maze? Is it different than a Labyrinth? Webster's tells us that it is a confusing, intricate network of winding pathways; specifically with one or more blind alleys, which is a pretty good definition. We might note that a maze is usually meant to be a puzzle that must be solved and therefore usually has a goal which is meant to be reached. Is a maze different from a labyrinth? Some writers reserve the word labyrinth to mean a confusing, intricate network of winding pathways with no blind alleys or loops (and therefore no puzzle), but in practice few writers seem to hold to this definition. The most famous labyrinth in literature, the Cretan Labyrinth of the minotaur legend, was definitely meant to be a puzzle with blind alleys. For our purposes, though, the words maze and labyrinth are interchangeable. The Egyptian Labyrinth The first recorded maze in history was the Egyptian Labyrinth. Herodotus, a Greek traveler and writer, visited the Egyptian Labyrinth in the 5th century, BC. The building was located just above Lake Moeris and opposite the city of the crocodiles (Crocodilopolis). Herodotus was very impressed by it, stating, "I found it greater than words could tell, for although the temple at Ephesus and that at Samos are celebrated works, yet all the works and buildings of the Greeks put together would certainly be inferior to this labyrinth as regards labor and expense." Herodotus added that even the pyramids were surpassed by the Egyptian Labyrinth.

Herodotus was told that the land of Egypt had been divided into twelve kingdoms, or nomes, each ruled by a king. The kings had come together to leave a memorial of themselves through this temple which was called ArsinoŽ, which means "the temple at the entrance of the lake." The entire building was surrounded by a wall and contained 12 courts with 3,000 chambers. The roof of the temple was composed of stone and the walls were covered with sculpture. On one side of the labyrinth was a pyramid 243 feet high. The temple was in two levels with half of the rooms above ground and the rest below. Herodotus was guided through the upper part of the labyrinth, but was not permitted to go underground. He was told that the rooms below contained the bodies of the kings that constructed the temple and the tombs of sacred crocodiles. The ancient writer Pliny in his book "Natural History," written in the first century AD, also talks a little about this labyrinth. He noted that the labyrinth contained palaces and temples to all the gods of Egypt as well as "banquet halls reached by steep ascents, flights of ninety steps leading down from the porticoes, porphyritic columns, figures of gods and hideous monsters, and statues of kings." Pliny goes on to say, "Some of the palaces are so made that the opening of a door makes a terrifying sound as of thunder. Most of the buildings are in total darkness."

Little remains of this once-impressive structure today. In 1700 a European traveler named Paul Lucas visited the site and published an account of the remains, including sketches, as he saw them. Over a century later K.R. Lepsius led an expedition and uncovered a series of brick chambers which he identified as the labyrinth. The location was not definately determined until Professor Flinders Petrie explored the site in 1888. Petrie identified the wall found by Lepsius as the remains of a Roman town and then went on to find the foundation of the actual labyrinth which measured 1,000 feet long by 800 feet wide. Archaeologists now believe that the temple was built by Amenemhat III around 4,000 years ago and the mummified remains of Amenemhat and his daughter have been found in the associated pyramid. The exact purpose of the building is still a matter of speculation, but one thing is for sure: it is the oldest-known structure to which the label labyrinth has been applied. The Cretan Labyrinth Certainly the most famous labyrinth of all time is that associated with the Greek myth of Thesesus and the Minotaur. According to the legend, King Aegeus was forced to pay tribute to King Minos of the Minoans, whose kingdom was on the island we now call Crete. Every year the tribute included seven young men and seven young maidens. Underground far below King Minos' palace at the city of Knossos lay a huge maze. Inside the maze Minos kept a monster called the Minotaur. The Minotaur was a hideous creature that was half man and half bull. The fourteen young people from Greece would be let loose into the maze, where they would become hopelessly lost and eventually be eaten by the monster. King Aegeus' son, Thesesus, decided to volunteer as one of the sacrificial victims so that he could attempt to kill the Minotaur. Thesesus was successful. He slew the Minotaur, then used a trail of twine he'd started laying down at the entrance of the labyrinth to find his way out of the maze. Archaeologists have found no evidence of a labyrinth structure at Knossos. In Roman times some writers suggested that a set of winding caves at Gortyan, on the south-side of Crete, might have been the Labyrinth. As similar as the description of this maze of passages is to the maze found in the myth, the story places the Labyrinth at Knossos, not Gortyan. If the Labyrinth was a natural cave augmented by man it must have been one similar to those at Gortyan located near Knossos. If so, the cave is now lost or has had its entrance destroyed. More recently archaeologists have suggested that the palace itself at Konossos was so complicated with so many levels, stairs and rooms it may have been the genesis of the labyrinth story. The Italian Labyrinth According to Pliny, who died in 79 AD, the tomb of the great Etruscan general Lars Porsena was alleged to contain an underground maze. Not much is known about the nature of the labyrinth there. The description of the exposed portion of the tomb is so strange that even Pliny makes it clear he had not observed this structure himself, but is quoting the writer Varro (116-27 BC). Church Mazes

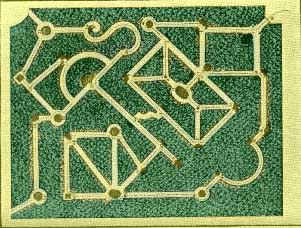

As the Roman Empire fell and the Middle Ages arose, labyrinths started to appear as a feature in churches as Christianity spread across Europe. These church labyrinths were not three-imensional, but appeared as art painted on walls or inlaid on the floor. The purpose of these labyrinths is a matter of conjecture. Some authorities hold that they represent difficulties and intricacies that beset a Christian during his life. Another view is that they are a symbol of the entangling nature of sin. Some of the larger floor versions of these labyrinths may have been used as the path for miniature pilgrimages. Priests sometimes would send parishioners on a distant pilgrimage as a penitence for sins. The labyrinth path may have been substituted if the sin was particularly small or the sinner was unable to undertake a distant journey because of ill health. The penitent would probably have had to negotiate the labyrinth on his knees while praying. The oldest-known church labyrinth is at the Basilica of Reparatus at Orleansville, Algeria, and dates from the fourth century AD. It is located in the pavement and measures about 8 feet in diameter. Many of these mazes were included as part of churches built in the 12th century in Italy and France. One of the largest was a part of the floor in the nave of Amiens Cathedral in France. It measured about 42 feet in diameter. Unfortunately this labyrinth, built in 1288, was destroyed in 1825. However, many fine examples of the church labyrinth are still preserved in cathedrals in Europe today. Turf Labyrinths

Church mazes never caught on in England, but in that country there developed a class of mazes which seem to be peculiar to that nation. Turf mazes were constructed and can still be found in or just outside, villages across the countryside. They range from 25 feet across to over 80 feet in diameter. Usually the path is cut into the ground about 6 inches. Typically they are given names like "Mizmaze", "Troy Town," "Shepherd's Race" or "Julian's Bower." The origin of this type of maze may date all the way back to Roman times. Pliny, in his Natural History, says that we must not compare the Egyptian labyrinth with "the mazes formed in the fields for the entertainment of children" suggesting these diversions may have a long history. A Welsh history book Drych y Prif Oesoedd published in 1740 makes note of the curious custom shepherds had of cutting the turf in the form of a labyrinth. Such an origin would seem to explain the term "Shepherd's Race" attached to many turf mazes. The name "Troy town" probably refers to a legend which says that the city of Troy had seven exterior walls arranged as a maze to frustrate an attacking force. Nazca Lines A strange cousin of turf mazes, but located on the other side of the world, are the Nasca lines. The lines are located on a high plain in Peru and were built between 200 BC and 300 AD. They form huge geometric shapes and pictures that can only be appreciated from the air. Many theories about the meaning of the lines exist ranging from surface maps of underground water to landing fields for UFOs. Some researchers have suggested that the lines may represent a path to be trod by the faithful from shrine to shrine as they meditate and pray. If the lines were indeed used in that way their purpose would seem to be very similar to that of the church labyrinths in Europe. Hedge Mazes

From the turf maze it is no big jump to perhaps the most famous form of full-size maze, the topiary, or hedge maze. While the use of hedges in gardens date back to Roman times, the earliest references to a topiary maze seem to appear in the 13th century in Belgium. By the sixteen century the hedge maze had spread to England as a landscape painting by the pain Tintoretto attests. In the later part of the 17th century, King Louis XIV had a labyrinth constructed as a part of the gardens at Versailles. This maze also included 39 groups of hydraulic statuary representing the fables of Aesop. Each of the characters who appeared to be speaking emitted a stream of water, representing speech. Perhaps the most famous hedge maze that still exists today is the Hampton Court maze in England. It is of no great size, only occupying a quarter of an acre, but it is still very popular despite its long history at that site. An earlier maze at Hampton Court preceded the construction of this one in 1690. Like most hedge mazes, the shrubs that form the Hampton Court maze's walls are taller than the height of most of its visitors. Only from a raised platform, or hillside, can the layout of a traditional hedge maze be ascertained. In recent years mazes similar to hedge mazes but constructed of corn stalks have become popular, particularly in the United States, during the fall season. Maze Solutions There are two forms of mazes: unicursal and multicursal. Unicursal mazes have no blind alleys and therefore do not pose much of a puzzle to those that negotiate them. A multicursal design, however, has blind alleys and branches and finding the "goal" of the maze presents a challenge. The mazes we have pictured so far have been two-dimensional with the path only running along a flat plain. Some mazes are made more complex by being three-dimensional with multiple levels and locations where branches pass from level to level. Needless to say a three-dimensional maze can be much more difficult that a two-dimensional maze, both to comprehend and negotiate. Mathematically, mazes with even more dimensions can exist, but may be difficult to build in the real world.

Since there are no blind alleys or branches in a unicursal maze no "solution" is needed. Multicursal mazes are a different story. The easiest solution for such a maze is to place a hand on one wall when starting and follow that wall. Each blind alley will be transversed one time in and out until the whole maze is completed, or the goal is found. This simple method can fail, however, if the goal is located within an "island" in the maze. An island is a section of the maze not connected with any of the exterior walls. Since the above method follows an exterior wall throughout the maze, the "island" is never penetrated. A maze can also be transversed by marking each path exiting from a node as it is used. A node is a point where the path branches in two or more ways. When arriving at a node the explorer should leave three chalk marks on the ground of the path he has entered if he sees that other paths at that node have not been marked. If other marks are present at the node the arrival path gets one mark. If the explorer sees that all the paths show marks he should turn around and retrace his steps, because the marks indicate he had already transversed the paths coming out of this particular node. If there are one or more unmarked paths, the explorer should select one, mark it with two chalk marks and follow it. If the explorer follows a rule that when entering the node he will never leave on a three mark-path unless there are no paths unmarked or with one mark only, he can be assured of visiting every part of the maze. Scientific Mazes While mazes are fun they also have a serious side. Mazes are often used in laboratory experiments to test a subject's ability to learn and remember. A lab rat will take some time when it first transverses a maze to find a food reward because it is randomly wandering. On consecutive tries, however, the rat will take less and less time as it learns and remembers the shape of the maze. Researchers can then ascertain how quickly the rat learns under different conditions by timing his trip through the maze. Making Mazes Mazes are fun. With tools as simple as a pencil and a piece of paper you can construct your own maze. The rules are simple. Make sure you have at least one path between the entrance and the goal. If you want a unicursal maze there are no branches. A multicursal maze has branches (also called blind alleys) but you should make them long enough that they are not easily identifiable as blind alleys from the branch and short enough that tracing them to a dead end does not tire the player. Full-size mazes can also be drawn on the ground with chalk or in the sand on a beach. Your imagination is the limit! Copyright Lee Krystek 2001. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

|