According to ancient greek myths, the great greek

King Aegeus was forced to pay tribute to King Minos of the Minoans,

whose kingdom was on the island we now call Crete. Every year

the tribute included seven young men and seven young maidens.

Underground far below King Minos' palace at the city of Knossos

lay a huge maze built for him by the

inventor and master architect Daedalus. Inside the maze Minos

kept a monster called the Minotaur. The Minotaur was a hideous

creature that was half man and half bull. The fourteen young

people from Greece would be let loose into the maze, the labyrinth,

where they would become hopelessly lost and eventually be eaten

by the Minotaur.

According to the legend, King Aegeus' son, Thesesus,

decided to volunteer as one of the sacrificial victims, so that

he could attempt to kill the Minotaur. Thesesus was successful.

He slew the Minotaur, then used a trail of twine he'd started

laying down at the entrance of the labyrinth to find his way

out of the maze.

So how much of this incredible tale is based on

reality? Ancient writers from Roman times argued that the Labyrinth

was a set of winding caves they knew were located on the south

side of Crete at Gortyna. In the early 19th century C.R. Cockerell

visited these caves and wrote in his journal that he and his

party entered the cavern through an inconspicuous hole in the

hillside of Mount Ida and unwound a length of twine to keep

from getting lost. "The windings," wrote Cockerell,

"bewildered us at once, and , my compass being broken,

I was quite ignorant as to where I was. The clearly intentional

intricacy and apparently endless number of galleries impressed

me with a sense of horror and fascination I cannot describe.

At every ten steps one was arrested, and had to turn to right

or left, sometimes to choose one of three or four roads. What

if one should lose the clue!"

|

A

sketch of the Gortyna cavern as seen in the 19th century.

|

The caves at Gortyna, as much as they might

seem to fit the legend are in the wrong place as the Labyrinth

was supposedly located at Knossos. Some writers have speculated

that another similar set of caves, now lost, near Knossos

served as the Labyrinth, but modern archaeologists have come

to another conclusion.

Archaeologists have found no evidence that a

horrible half-man, half-bull-like creature existed at Knossos.

However, they have found what looks like a labyrinth. The

labyrinth wasn't built in a cave below the palace, though.

It was the palace.

The Minoans are a mysterious people. We do not

know where they came from, but they seemed to have arrived

in Crete about 7000 BC. By all indications the Greeks feared

the Minoans, but the Minoans did not seem like a warlike people

(their cities had few fortifications). Little is known about

the Minoan's religion or their form of government. We cannot

read the writing they left behind. In fact, researchers have

been unable to figure out even by what name the Minoans called

themselves. The term Minoan comes from the legend of King

Minos and was coined by archaeologists because they needed

a term to describe their discoveries at Knossos.

|

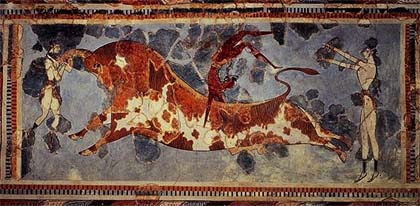

A

fresco from the Minoan palace at Knossos showing the

sport of "bull leaping."

|

If the Minoans had power it must have come from

trade, not war. They exchanged goods with peoples from all

around the eastern Mediterranean. Ostrich plumes came from

northern Africa, alabaster from Egypt, gold and silver from

the Aegean Islands and ivory from Syria. They alll passed

through Minoan hands, making Mionan profits, on their way

to distant destinations.

The wealth from the trade financed a number

of palaces on Crete, the largest of which was the palace at

Knossos. Archaeologists are not exactly sure who lived in

the Knossos palace. However, they have uncovered a quantity

of ceremonial and religious imagery there. This leads some

to believe that the chief occupant of the building was a 'priest-king'

who had the dual function of leading the state and the religion.

Other scholars see the palace as a only a temple. Others as

a center for trade.

Whatever the palace's function, the building

itself was enormous. It contained hundreds of rooms at many

levels grouped around a central courtyard. The palace had

storerooms, bathrooms, private apartments, public rooms, workshops

and even what appears to be a throne room. Some of the storerooms

contained dozens of huge jars, called pithoi, which

were used to contain olive oil. According to some estimates

60,000 gallons of olive oil could be put in these, which is

a testament to the Minoan's wealth.

|

This

siliver coin from Knossos dated at around 500 B.C. shows

the Minotaur on one side and the Labyrinth on the other.

|

While there is no archaeological evidence of

a labyrinth, the palace itself to a visitor must have seemed

like an intimidating maze of corridors, staircases and rooms.

This is probably where the legend of the labyrinth began.

An early version of the palace was started around 1900 BC,

but was demolished for a grander one in 1700 BC. Unlike the

Greeks, the Minoans did not consider symmetry an important

attribute of architecture. Rooms and halls seem to be added

almost at random, though they were undoubtedly placed with

a practical purpose in mind. The lack of symmetry does not

mean the palace was ugly. Each room had its own beauty and

many were decorated with frescoes. The palace reflected the

Mnoans practicality. Much of the structure and columns were

made of wood, which was more likely to survive an earthquake

than stone. The palace had a sanitary drainage system to take

wastewater away from the apartments. The drainage channel

was even designed with zigzags and basins to slow down the

water to prevent overflows. Many of the rooms are partly underground

to keep them cool in the summer and warm in the winter. Colonnaded

porches allow cool breezes in, but kept out the hot sun.

If the palace is the origin of the labyrinth

myth, where did the legend of the Minotaur come from? We know

that the Minoans had a fascination for bulls. Their most mysterious

art shows human figures, some of them girls, grabbing the

horns of a bull and leaping over it. Archaeologists have wondered

if this strange and dangerous activity really did take place.

If it did, was it merely a sport, or did it have some religious

significance? Recent archaeological excavations have shown

an arena-like structure outside one of the Minoan palaces

that might have been the site of these mysterious activities.

Whatever the significance of the bull-leaping, it was probably

the genesis of the Minotaur myth.

Why bulls? Crete is subject to earthquakes.

Perhaps the violent and unpredictable movements of the earth

seemed to them like the temperamental acts of a creature such

as a bull. The Greek god Poseidon was known as the 'earth-shaker'

and was connected to bulls, so perhaps the Minoans were worshiping

an earlier form of this god in their ceremonies.

Archaeologists

think that the end of the Minoan culture came about 1450 BC.

Seventy miles away, a volcano exploded on the island of Thera.

This caused a huge tidal wave to hit Crete which destroyed

many major buildings and probably their fleet of ships. The

wave ended the Minoan's ability to conduct trade, causing

them to quickly lose power in the eastern Mediterranean.

Archaeologists

think that the end of the Minoan culture came about 1450 BC.

Seventy miles away, a volcano exploded on the island of Thera.

This caused a huge tidal wave to hit Crete which destroyed

many major buildings and probably their fleet of ships. The

wave ended the Minoan's ability to conduct trade, causing

them to quickly lose power in the eastern Mediterranean.

Some scholars suggest that the end of the Minoan

culture may have inspired stories about the continent of Atlantis.

The story of the destruction of a powerful and sophisticated

culture by water in one night seems extremely similar, though

the dates and location must have been exaggerated over time.

Copyright Lee Krystek

2001. All Rights Reserved.