pop up description layer

HOME

Cryptozoology UFO Mysteries Aviation Space & Time Dinosaurs Geology Archaeology Exploration 7 Wonders Surprising Science Troubled History Library Laboratory Attic Theater Store Index/Site Map Cyclorama

Search the Site: |

|

Notes from the Curator's Office:

The Roots of Indiana Jones Indiana Jones was spawned in the mind of George Lucas as a way of bringing the short serial movies he'd watched as a child back to life. What were these cliffhangers and why were they so inspiring? (5/08) I'm a huge Indiana Jones fan, so this month is a pretty big deal for me. The road to the fourth film, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, has been a long one. The previous film, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, came out in 1989 and at the time it seemed like it would be the last film in the series. As Lucas explained in an interview in Vanity Fair, he and collaborator Steven Spielberg didn't want to make a film without a first-class script, and it was years before they had one they could agree upon. Just in time, too, as protagonist Harrison Ford was turning 66, a dangerous age for doing your own stunts. The movie opens on May 22nd, but like many rabid Indy fans, I've been anticipating the premiere since the filming wrapped last summer. To fill in the gap I've screened all the former films again and even went on an eBay hunt to find old VHS episodes of Lucas's 90's TV show The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones. (A young peoples' program which told about Indy's life in his early years. The show, which serves up some nice semi-educational historical fiction, was nominated for several Emmys and won two.) Having gone through most of my Indiana Jones material, and still a month short of the opening, however, I began to spend my time pondering about where the Indy series came from in the first place. Hawaii Connection As any Indy fan can tell you, the idea for the movies was first brought to life on a beach in Hawaii in 1977. Lucas, nervous about the premiere of his latest effort, Star Wars, took a vacation and invited close friend and fellow filmmaker Steven Spielberg to join him. After the news that Star Wars was a success, the pair turned to the discussion of future projects. Spielberg had longed to direct a James Bond flick, but had been turned down. He was thinking of approaching Bond producer Cubby Broccoli a second time, but Lucas told him, "I've got something better than that. It's called Raiders of the Lost Ark." Spielberg loved the idea, and with him directing and Lucas producing, the adventure was born. Lucas had come up with the idea several years before as a distraction from working on his film American Graffiti. The concept came from the Saturday matinee serial shorts made by Republic Studios that Lucas had watched as a kid. Being slightly younger than the filmmaker, I was unfamiliar with this type of movie. By the time I was a kid, Saturday morning cartoon shows had replaced the matinee. So I decided to see what I could find out about these old serials. How much of them actually made it into Indiana Jones?

The Republic Serials My venture into this was to use the internet to look up "Republic Serials." Republic Entertainment, Inc. was founded in 1935 when six smaller studios were put together. One of the things Republic specialized in was "B" movies. Usually these films were produced on a shoestring budget with low production values, shorter running time (typically 70 or 80 minutes) and unknown actors. During the 40's and 50's, movie theaters would use the "B's" as the first show on a "double feature" billing. During this period, Republic also produced serials or as they were sometimes called "chapter plays." Typically these consisted of a long, action-packed story, cut into individual episodes. Each week a new episode would reach the theater, encouraging movie goers to return. To make the need to return even more compelling, the serial producers would end each episode with a "cliffhanger." The hero, or heroine, was placed in mortal danger by the bad guy with the resolution not coming till the episode the following week. Sometimes the cliffhanger was literally that: The hero hanging by his finger tips over a fatal drop while his arch-enemy looks on. Other forms of peril might include being tied to a railroad track before an oncoming train, strapped down to a log going through a buzz saw, trapped on a sinking ice floe in Arctic waters, etc. While Republic filmed their famous serials from the mid-30's through the mid-50's, the art form actually goes back even further. In 1912, Edison's production company - yes - Thomas Edison, the guy we usually associate with the light bulb, he used to be a filmmaker too - released What Happened to Mary? This 12-part production wasn't just one of the first movie serials, it also established the "damsel in distress" sub-genre of having a villain put a pretty young woman into danger, only to have her be rescued by the hero at the last minute. Though this sounds like the perfect cliffhanger, these early serials placed this action in the middle of the episode, not at the end. Two years later one of the most famous silent films of all time, The Perils of Pauline, came out following the same "damsel in distress" formula. This type of plot was so popular that filmmakers were soon straining to find titles like The Hazards of Helen, where they could rhyme the heroines name with some word meaning danger. Interestingly enough, while some feminists accused this formula of being a thinly-veiled male erotic fantasy, these early efforts were actually heavily marketed to women.

These silent films were the first heyday of serials with a few of them having as many as 119 episodes. They were cheap to produce and drew audiences back week after week. This ended though with the advent of talking motion pictures. The need to add sound greatly increased the cost of production in the middle of the Great Depression when money was scarce. Many of the early, smaller studios went out of business. One of the few that survived was Mascot, which became one of the six studios folded into Republic. The Golden Era What followed was a new era of serials - some call it the "Golden Era" - where the films were slightly more sophisticated, though still cheap productions by feature standards. They now had sound and musical tracks. Each serial started with a thirty-minute episode which established the premise, followed by 20-minute chapters filled with action and mystery, ending with the cliffhanger. There were usually a dozen episodes, though some had as few as ten and others as many as eighteen. One of the measures used to keep the costs of the serials down was to reuse as much previously shot footage as possible. Republic owned a Packard limo and a Ford wagon that were used in film after film so that they could match new footage up with chase scenes shot previously. Often these vehicles were shown following the same van which was actually the studio sound truck. Expensive special effects were reused whenever possible: A car bursting in flames as it went over a cliff or a miniature of a train exploding were worked into scripts again and again because the footage was available for free. Ronald Davidson was one of Republic's most successful writers/producers because he had been around a long time and knew where all the old footage was located. Serials released in the 50's often had footage that had actually been shot in the 30's.

While Republic was the king of serials, both Universal and Columbia also invested in them. Just as today, the studios found comics a great source of characters and stories. Republic licensed Dick Tracy, Captain America, and Captain Marvel . Columbia got Batman, Superman, and the Phantom. Universal bought the rights to Buck Rodgers, the Green Hornet and, arguablly the most popular character in a movie series of all time, Flash Gordon. The Flash Gordon series was such a hit that it was booked into many of the classier movie theaters that hadn't before dealt with serials. Archive.org I wanted to know where I could take a look at some of these historical masterpieces myself. A DVD copy of Flash Gordon (The original serial and two sequels) goes for about $12 bucks on Amazon and Columbia's The Batman from 1943 in DVD format will set you back $20. Being a cheapskate I looked for another way to take a peek at these at a minimum price. My best solution was archive.org. Archive.org is a non-profit organization dedicated to "building a digital library of Internet sites and other cultural artifacts." The archive has a special section dealing with moving images which contains a lot of public domain material. The videos are mostly uploaded by volunteers who take the time to put the material in several different sizes and formats. If you are in a hurry, you can usually download a small screen version so you can get a quick look at the movie. If you don't mind the wait, often there are versions available which can give you resolutions equivalent to your typical standard definition TV screen. Of course with so many people uploading there are occasional problems with a particular version not working or something being uploaded that doesn't belong there (there was a nice copy of Plan 9 from Outer Space till they realized it was still in copyright and had to be removed). All in all though, the volunteers do a pretty good job of finding and putting up old motion pictures. There is an extensive collection of serials which never had their copyrights renewed. These include Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe, Undersea Kingdom (starring a character called "Crash" Corrigan), The Great Alaskan Mystery, Radar Men from the Moon, along with a host of others. While this still represents a fraction of the number of serials made during the golden age of serials, it is enough to give movie buffs a good idea of what the format was all about and what Lucas and Spielberg were seeing as kids.

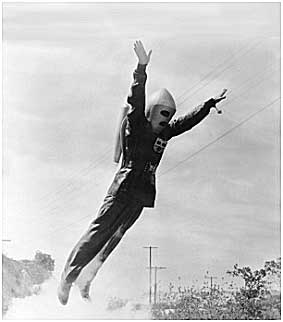

Now I'm not saying that by modern standards these things are masterpeices of entertainment. The scripts are simple and formulistic (after all, there has to be a cliffhanger every 20 to 30 minutes or so). The sets cheap and the props unrealistic, especially to modern eyes. Plus, they are long (typically five hours or more of film time which is hard to take in one sitting - which, of course, was not the original idea). However, if you are a movie buff or an Indy fan, you might want to spend a few minutes and download a half dozen episodes. I would recommend The Great Alaskan Mystery. Its storyline - Nazi spies after a secret weapon being tested in the Alaskan wilderness - reminded me a lot of the Indy plots. Mechanical Monsters and Radar Men Lucas and Spielberg aren't the only filmmakers that have drawn inspiration from pictures of the 30's and 40's. I'm a huge fan of the highly underrated 2004 film Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow. This tale, written and directed by Kerry Conran, and realized mostly through computer graphics, takes place in an alternate universe of the 1930's that includes giant flying robots and mad scientists trying to end the world. Wandering about archive.org I came across an old Superman cartoon that clearly had inspired Conran's vision of his own picture (check out Superman: The Mechanical Monsters from 1941). For another example, compare the 1952 serial Radar Men from the Moon with Disney's 1991 film The Rocketeer. True, the Disney flick comes from the 1982 comic book by Dan Stevens. Stevens, however, was inspired to create his character after seeing Radar Men and several other related serials. It is unfortunate that some of the people who might enjoy finding these old films on archive.org - senior citizens - will have the most difficulty navigating the site. My guess is that if you have a father or grandfather who grew up in that era and you have the talent to transfer some of archived material to a DVD, it would make a nice present for father's day. It would be a chance for that person to relive those youthful hours in the local cinema cheering the good guy and booing the villain.

We have to thank at least two of those kids, Lucas and Spielberg, who managed to carry the serials into the next generation through the Indiana Jones films. They gave them better production values, but at the heart they are the same action-packed cinema we see in the old serials. So is Kingdom of the Crystal Skull the end of the Indy films? The last in the series inspired by the serials? Jim Windolf, who wrote the article for Vanity Fair doesn't think so. In a follow-up story on the Vanity Fair, website, he theorizes that the young actor Shia LaBeouf, who may (or may not, we won't know till the new film is out) be Indy's son, may star in a continuation of the films. If so, well I suspect I'll be there in the theater, cheering the hero and booing the villain. If not, well, just look for me at archive.org. Copyright 2008 Lee Krystek. All Rights Reserved. |

|

Related Links |

|

}

|