|

Jules

Verne

|

Jules

Verne: An Author Before His Time?

This 19th century author's novels predicted

submarines, flying machines, skyscrapers and even the moon landing

while at the same time inspiring some of the world's most important

scientists. How did he do it?

On the 31st of January, 1863, a small volume began

appearing in bookstores all over France. It was the adventure

of three travelers, led by a Dr. Fergusson, who dared to penetrate

the interior of darkest Africa using a balloon. The brave explorers

in the story risk angry, spear-carrying natives, ferocious baboons,

and slow death by dehydration during their trip. Readers found

themselves puzzled by this account. Was it fact or fiction?

It read like an authentic travel diary, including detailed descriptions

of natural phenomena that was seen and notes taken on the longitude

and latitudes as the travelers moved, but the adventures seemed

fantastic!

In the Paris daily Le Figaro a review read,

"Is Dr. Fergusson's journey a reality or is it not? All

we can say is that it is bewitching as a novel and as instructive

as a book of science. Never have the serious discoveries of

celebrated travelers been summed up as well."

The title of this amazing work was Five Weeks

in a Balloon and its first-time author was a man named Jules

Verne.

Early

Life

Jules Verne was born on February 8, 1828, in the

city of Nantes, France. His father, Pierre Verne, was a lawyer.

From the family's summer house just outside the city, young

Jules could look out and see the great docks and shipbuilding

facilities of the region. Jules prided himself at having grown

up "in the center of maritime life of a great commercial

city, port of call of innumerable long voyages." He watched

the great clipper ships and three masted schooners come and

go as he used his imagination to climb their masts and ride

the great vessels to foreign ports of call.

For payment of a franc Jules and his younger brother

Paul would rent a boat for the day and go sailing behind their

summer house. It was during one of these times that Jules found

himself stranded about 30 miles downstream when a plank came

lose and the boat sunk. Stuck on a small islet, he was forced

to wait until low tide to wade across to the mainland and walk

home. The incident was embellished by an early biographer into

an attempt by the young Verne to sail off across the Atlantic

as a cabin boy on a ship headed for the West Indies, only to

be rescued by his father at the last moment. The tale, while

a favorite with Verne fans, shows not the slightest sign of

being true.

Verne's father, wishing to see his son follow

in his footsteps, sent him to Paris to study law. While there

he found himself attracted to the theater. Encouraged by his

friend, the elder Alexandre Dumas (author of The Three Musketeers),

Verne tried his hand at writing plays. The first one was produced

in 1850. Over the next ten years Verne tried to make a living

as a playwright. He gave up the law (to the great alarm of his

father) to create a series of not terribly successful works

for the stage including The Companions of the Marjolaine

and Blindman's Bluff. In order to support himself Verne

became a stockbroker, a career that did not capture his heart,

but gave him enough financial stability to marry a widow named

Honorine in 1857. In 1861 their only child was born, Michel

Jean Pierre Verne.

Novelist

It was the year 1862 in which Verne's career took

off in a new direction. There is legend that he stood on the

steps of the Paris stock exchange and declared to his associates

there, "My boys, I believe that I'm about to desert you.

I had the kind of idea Emile Girardin says every man must have

to make a fortune. I've just written a new kind of novel, and

if it succeeds it will be an unexplored gold mine. In that case

I'll write more such books while you're buying your stock. And

I think I'll earn the most money!" When his friends laughed

at his comments, he replied, "Laugh, friends, we'll see

who laughs longest."

|

Early

illustration of Verne's manned projectile from the book

From the Earth to the Moon.

|

It is hard to say if the above story is true.

However, Verne certainly did invent a new kind of novel, and

it did bring him fortune and fame.

When he set out to write Five Weeks in a Balloon

Verne had no knowledge of ballooning, nor had he ever been to

Africa. He probably drew heavily on the writings of others including

Edgar Allan Poe's The Balloon Hoax, a story about a group

of Englishmen who accidentally cross the Atlantic in a balloon,

and Poe's The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfaall,

a tale about a trip to the moon in a balloon.

To make his accounts of Africa realistic Verne

undoubtedly relied on magazines such as Louis Hachette's Le

Tour du Monde-Nouveau Journal des Voyages. This weekly publication

contained articles on explorations around the world and included

maps, illustrations of ships, and descriptions of customs in

remote locations. These details would have certainly been invaluable

to Verne in fleshing out his novel.

The

Publisher

Every writer needs a publisher, and Verne's was

a man by the name of Pierre-Jules Hetzel. Hetzel and Verne were

introduced to each other in 1862 by a mutual friend, writer

Alfred de Brehat. Shortly afterward they entered into a partnership

that would last most of their lives. In Hetzel, Verne had found

the ideal publisher, and in Verne, Hetzel had found the ideal

writer. Hetzel's careful editing and insightful suggestions

for changes to Verne's manuscripts perhaps made Hetzel nearly

as responsible for their success as was Verne himself. Together

they would turn out one lucrative novel after another.

Hetzel also introduced Verne to Felix Nadar, a

renaissance man with interests in aerial navigation and ballooning.

Though it is impossible to say if Nadar contributed any ideas

to Five Weeks in A Balloon, we do know that Nadar, in

turn, introduced Verne to his circle of scientific friends.

Conversation among them undoubtedly guided Verne while writing

his early scientific stories. Later when Nadar founded the Society

for Encouragement of Aerial Locomotion by Means of Heavier-Than-Air

Craft, Verne was listed as a member of the board.

Though many people think of Verne as a scientist

or a world traveler, in truth he was neither. Much of his research

for his works was done through reading books and periodicals

or discussing the scientific breakthroughs of the day with his

knowledgeable friends. We are often amazed when his scientific

predictions in his books turn out right, but the truth is we

more easily forget the ones that are wrong.

Verne realized that he had finally found his place

in the world and threw himself into his work with great enthusiasm.

In a progress report to Hetzel while working on a novel about

exploring the North Pole he wrote, "I'm in the middle of

my subject at 80 degrees latitude and 40 degrees centigrade

below zero. I'm catching cold just writing about it!" In

the next ten years he was to create many of his classic novels

for which he is best remembered.

Even before the first copies of Five Weeks

in a Balloon went on sale, Verne was hard at work on this

next adventure: The tale of a tenacious explorer named Captain

Hatteras and his difficult journey to reach the North Pole.

Hatteras's odyssey was published as two books, The English

at the North Pole and The Wilderness of Ice, but

before these were released Verne was already starting on a book

that is still widely read today, Journey to the Center of

the Earth.

Even in these early books it is easy to see that

Verne was fascinated in building a closed universe in which

his characters could act. In some cases it was a balloon basket,

in others an island, cave or a ship. Almost always Verne's heroes

are characters that can thrive in that universe, making do with

whatever available materials there are to build a solution to

the obstacles that arise.

Paris

in the 20th Century

Though today we think of Verne as an optimist

and an unswerving supporter of scientific progress, this was

not really the case. Early on he had doubts about the effects

of too much technology on human lives. In 1863 he penned Paris

in the 20th Century, a novel about a young man living in

a future world with skyscrapers of glass and steel, high-speed

trains, gas-powered automobiles, calculators, and a worldwide

communications network. The hero cannot find happiness in this

highly materialistic environment, however, and comes to a tragic

end.

Verne took this novel to Hetzel, who declined

to publish it. Hetzel, knowing the mood of the times, thought

that the novel would not be successful and might even damage

Verne's career. "Wait twenty years to write this book,"

Hetzel wrote in the margins. "Nobody today will believe

your prophecy, nobody will care about it." Verne followed

Hetzel's advice and the manuscript was dropped into a safe where

it lay until 1989 when it was discovered by Verne's great-grandson.

It wasn't until Hetzel's death in 1886 that a more pessimistic

side of Verne reemerged in his literature.

From the Earth to the Moon (1865) was Verne's

next major novel and the resemblance to the actual Apollo program

is uncanny. Following the civil war a group of gun enthusiasts

decides to fire a cannonball to the moon. At first the flight

is to be unmanned, but then the French daredevil Michel Ardan

(an anagram for Verne's friend Nader) volunteers to ride in

it. To test the idea of manned flight they launch a cat and

a squirrel (NASA would later use monkeys) and recover them at

sea. Two Americans join Ardan and the three of them (the same

number of astronauts as the Apollo program used) are launched

from an enormous cannon located in Florida just a few miles

from where the Kennedy Space Center would eventually sit. When

they return, they splash down in the Pacific, another similarity

to the first real moon shots. The book ends with the successful

launch of the 19th century astronauts. Readers would have to

wait four years until the sequel was published to find out what

happened to the intrepid adventurers.

In 1867, Verne, accompanied by his brother Paul,

made his single trip to North America crossing on the huge steamship,

the Great Eastern. Ironically, as much as Verne was fascinated

by the United States and the American people, he only stayed

a week. In that short amount of time he was able to cram in

a visit up the Hudson River to Albany, then on to Niagara Falls.

The short trip would remain locked in Verne's memory, with portions

of his experiences appearing in several of his later works.

20,000

Leagues Under the Sea

|

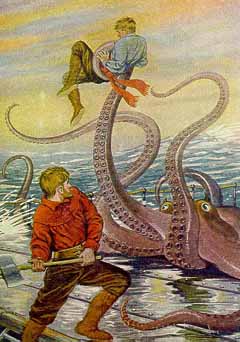

Nemo

and Aronnax explore Atlantis in this early 20th century

illustration.

|

His idea for his next major novel, 20,000 Leagues

Under the Sea, was perhaps sparked by a note from fellow

Hetzel author George Sand in 1865. After reading several of

Verne's novels, she wrote "...I have only one regret concerning

these stories, which is to have finished them and not to have

a dozen more to read...I hope that you will soon take us to

the depths of the sea and have your characters navigate in diving

vessels that your science and imagination will manage to improve."

It took years for Verne to complete what is probably

his most beloved book. In it his characters Professor Pierre

Aronnax, his manservant and Canadian harpooner Ned Land join

a United States expedition to kill a sea monster that has become

a menace to navigation. They attack the creature, but realize

too late that the monster is actually a submarine. Thrown into

the sea during the battle, Aronnax and his companions become

unwilling guests of the ship's owner, the mysterious Captain

Nemo. Nemo, a genius of unknown nationality, has cut ties with

humankind on the land and lives his life totally aboard his

submarine, the Nautilus. He refuses to let his guests

return to the land, but takes them on a series of adventures

under the sea. These include walking in the sunken city of Atlantis

and fighting giant octopi that attack the ship. As time goes

on, it becomes apparent that Nemo is waging a war against some

nation he holds responsible for the death of his wife and children.

When the Nautilus is pulled into the giant Maelstrom whirlpool

off of the coast of Norway, Aronnax and his companions escape

in a small boat, but the fate of the submarine and Captain Nemo

are unknown.

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was released

in two volumes, the first appearing in 1869 and the second in

1870. Before it was completed, there was a lively exchange between

Verne and Hetzel over the nationality of the mysterious Nemo.

Verne had originally planned that the Captain would reveal himself

as a Pole, avenging himself against the Russians who had killed

his wife and taken his children to Siberia where they had died.

The readership of Hetzel's magazine included, however, Russians

so Verne's publisher insisted Nemo's enemies not be named. Verne

unwillingly conceded to this demand, leaving both the nationality

of Nemo and his attackers a mystery until a later book.

In 1872 Verne completed the novel that would be

the most popular in his own lifetime, Around the World in

Eighty Days. The story of the reserved Englishman, Phileas

Fogg, who bets his entire fortune that he can travel around

the globe in less than eighty days was not only a successful

novel, but was produced on several different occasions for the

stage during Verne's lifetime. This was something that undoubtedly

made Verne, a playwright from his earliest days, very happy.

Mysterious Island, Verne's next major novel,

had a rough start. For many years Verne had wanted to write

a Robinson Crusoe-type novel about a group of people stranded

on an island. His first attempt, Uncle Robinson, was

flatly rejected by Hetzel. "Where is the science?"

the publisher wrote in the margins, "Drop all those people

and begin with new ones!" he added.

Verne's second try pleased Hetzel more. The books

starts at the end of the U.S. Civil War when five companions

escape from behind confederate lines in a balloon. The trip

lasts a lot longer then they expected. They are swept out to

sea and after several days land on a remote island dominated

by a volcano. A mysterious agent, later revealed to be the dying

Captain Nemo, helps them survive (in this book Verne finally

reveals the nationality of the Captain, but by this time it

has been changed to Indian and his enemies are the English).

The volcano finally explodes, destroying the island, but not

before the group is rescued.

In the years that followed Verne moved away from

scientific novels, but returned in 1886 with the Clipper

of the Clouds. In this story the evil genius Robur threatens

the world from the Albatross, a flying ship which maintains

its altitude through the use of helicopter-type rotors. At the

time, the question of whether the future of air travel was with

heavier-than-air craft or balloons was being hotly debated.

Verne, a supporter of heavier-than-air flight, had intended

to promote the idea through this book

Late

Life Misfortunes

|

The

attack of the octopi upon the Nautilus in 20,000

Leagues Under the Sea.

|

Eighteen-eighty six was a difficult year for Verne.

On March 9, Verne's nephew, Gaston, fired two shots at the famous

author just as he was coming home from his club near his home

in Amiens. One bullet missed, but the other entered Verne's

left shin. The wound was slow to heal and would leave him limping

for life. It is unclear why Gaston assaulted his uncle, but

it appears he was mentally unbalanced. He lived out the rest

of his life in an asylum.

Shortly after the shooting, Verne's longtime friend

and publisher Peirre Hetzel died. Although the publishing arrangement

would continue through Hetzel's son, Jules, Verne had lost a

major confidant. "I've never saw my father as affected

as he was when told of this misfortune," wrote Verne's

son, Michel to Jules Hetzel.

If there was anything positive to come out of

this difficult time it was that Verne and his only son were

drawn closer. Michel had been rebellious and difficult through

most of his life. At one point, when he was 16, Verne had even

shipped him off to spend eighteen months on a steamer going

around the world in hope that the time at sea would teach him

some responsibility. This failed, but his father's close brush

with death seemed to cause Michel to take life more seriously.

In his later years Verne wrote a number of books

and stories concerned with the misuse of technology and its

impact on the environment. In Propeller Island, he lamented

destruction of the native cultures of various Polynesian islands.

In the story The Ice Sphinx he predicted the decimation

of whale populations. His book The Begum's Fortune warns

that technology and scientific knowledge in the hands of evil

people can lead to destruction.

Verne continued to work and produce novels until

his death on March 24th, 1905, at the age of 77. Several of

his novels that were either finished or in progress at the time

of his demise were published after his death, including The

Lighthouse at the End of the World. His son Michel edited

much of the unfinished material and added missing chapters himself

when necessary. All in all, Verne had written over 70 books

and created hundreds of memorable characters.

The Verne legacy, though, is not only his words,

but his readers. Science Fiction writer Ray Bradbury once said,

"...we are all, in one way or another, the children of

Jules Verne." Admiral Richard Byrd said on the eve of his

polar flight, "Jules Verne guides me." William Beebe,

one of the first men to explore the depths of the sea in a bathysphere,

got interested in oceanography because of 20,000 Leagues

Under the Sea. Robert Goddard, considered the father of

rocketry, was an avid Verne reader as a child.

The Verne imagination, both through his books

and derivations of his works that have appeared in stage and

motion picture form, continue to entertain and inspire people

today almost a hundred years after his death. It is likely they

will continue to do so for many years to come.

Copyright 2002. Lee Krystek.

All Rights Reserved.

A

Partial Bibliography

Jules

Verne: An Exploratory Biography by Herbert R. Lottman, St.

Martin's Press, 1996.

Jules

Verne, Misunderstood Visionary by Arthur B. Evans and Ron

Miller, Scientific American.

The

Jules Verne Encyclopedia by

Brian Taves and Stephen Michaluk. Scarecrow Press, 1996