The

Rise of the Zombies

|

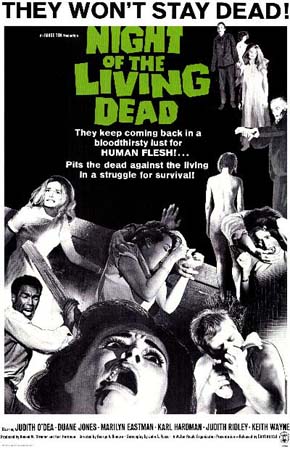

George

Romero's 1968 low-budget, film classic Night of the

Living Dead was a turning point for zombies.

|

Vampires have been popular figures in horror since

Bram Stoker wrote Dracula in 1897. The root of werewolf

folklore can be traced all the way back to the ancient Greeks.

Zombies, in their current form, however, have only shuffled

their stiff-legged corpses onto the silver screen in the last

few decades. Where did the zombie myth come from and why are

they now so popular?

Zombie

History

The term itself, zombie, actually goes

back many centuries before Hollywood appropriated it for horror

films. The root of the word comes from the language of Kikongo

spoken by the Bakongo and Bandundu people living in the African

Congo. Linguists think the expression comes from the related

term nzambi which means "god." The religion in this region

of the world was Vodun. When captured and forced into

slavery in the New World, West Africans brought their religion

with them. There it was mixed with other African traditions

and Christianity. The result was the folk religion of Vodou

(sometimes spelled Voodoo). Vodou eventually became a

major faith on the island of Hispaniola and in the two countries

that share that land, the Dominican Republic and Haiti.

In Vodou a zombie is a person who has died and

then been raised from the dead by bokor (a Vodou priest).

The zombie's soul is removed and he is rendered into an almost

robotic state following the orders of his bokor without question

or self-awareness. Often the bokor will put the zombie to work

as a form of free labor.

As you might guess, this kind of nightmare scenario

made for some great horror stories. The concept was introduced

to western culture in 1929 by W.B. Seabrook in his travelogue

to Haiti called The Magic Island. Seabrook, a former

editor of the Augusta Chronicle in Georgia, was an odd

figure fascinated with the occult, Satanism and folk religions.

While traveling in West Africa he claimed to have tasted human

flesh reporting that "the roast, from which I cut and ate a

central slice, was tender, and in color, texture, smell as well

as taste, strengthened my certainty that of all the meats we

habitually know, veal is the one meat to which this meat is

accurately comparable."

|

In

1936 anthropologist and writer Zora Neale Hurston visited

Haiti and interviewed a woman she thought might be a zombie.

|

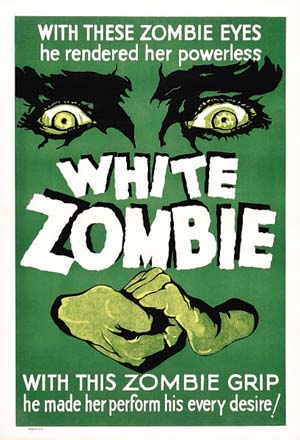

Shortly after Seabrook's book came out the ideas

within it were turned into the first zombie movie: 1933's White

Zombie, starring Bela Lugosi. In this film Lugosi is the

evil Haitian Vodou master who enslaves a young, pretty girl,

Madge Bellamy, as a zombie until she is rescued by her fiancée.

Critics bashed the movie for poor acting and an

over-the-top storyline. However, Lugosi was well-known for his

roll as Dracula in the 1930 Universal picture of the same name,

and his fame no doubt assisted the White Zombie at the

box office. It did well enough to warrant a 1936 sequel, Revolt

of the Zombies. After that a number of other zombie films

appeared including The Ghost Breakers (1940), King

of the Zombies (1941), I Walked with a Zombie (1943),

and The Plague of the Zombies (1966).

Science

and the Zombie

Eight years after Seabrook's visit to Haiti, author,

folklorist and anthropologist, Zora Neale Hurston, visited the

country and while researching Vodou folklore met a woman named

Felicia Felix-Mentor. Records showed that Felix-Mentor had died

almost 30 years earlier in 1907, yet she was found wandering

the streets in 1936. After making her way to her father's house

(which by that time was owned by her brother) she was identified

by her relatives. Doctors examined her and reported that "her

occasional outbursts of laughter were devoid of emotion, and

very frequently she spoke of herself in either the first or

the third person without any sense of discrimination. She had

lost all sense of time and was quite indifferent to the world

of things around her." Hurston interviewed Felix-Mentor at length

and believed that she had been made into a zombie. Hurston didn't

think that bokors could actually raise people from the dead,

but suspected they drugged them with some unknown potion that

gave the victims the appearance of having died. The priests

then raided the cemetery, retrieved the person, and kept them

in a zombie state using other powerful drugs. Hurston pointed

out that in Haiti bodies are interned above ground and without

embalming, making the chances of a successful "resurrection"

a realistic possibility.

|

The

poster from 1933's White Zombie.

|

Another scientist took a look at zombies in 1982

when Wade Davis, a Harvard ethnobotanist, visited Haiti. According

to his investigations bokors used tetrodotoxin (a neurotoxin

found in the flesh of the pufferfish) to simulate death in the

victim. When the victims awakened the priest would put them

into a psychotic state by giving them a drug like datura.

Wade contended that the person's culturally-learned beliefs

- that they had died and were now zombies - helped reinforce

their obedient behavior.

He supported his claims by citing the case of

Clairvius Narcisse, a Haitian man who was recorded to have died

in 1962, but was found alive several years later. According

to Narcisse, he had quarreled with his brother, who then hired

a bokor to poison Narcisse with the pufferfish toxin (introducing

it through scratches in his arm). A funeral was held for Narcisse,

but his body was recovered later by the bokor, who used drugs

to make Narcisse into a zombie so he could work on the priest's

plantation. When the bokor died, the drugs eventually wore off

and Narcisse returned to his family.

Davis had his skeptics, but that didn't stop him

from writing two books on the subject: The Serpent

and the Rainbow in 1985 and Passage of Darkness:

The Ethnobiology of the Haitian Zombie in 1988. The

Serpent and the Rainbow was made into a zombie movie in

1988. Directed by Wes Craven, it starred Bill Pullman as the

scientist who tracks down the macabre truth.

Night

of the Living Dead

It had been almost twenty years earlier, however,

that the history of the zombie film had made an unexpected turn.

Up to that point zombies were more victims than perpetrators.

People feared being turned into zombies, not being eaten by

them.

In the mid-1960's a young TV commercial director

named George Romero, along with some business partners, decided

to try their hand at making a low-budget horror film. Several

scripts were written before Romero came up with the idea of

reanimated human corpses that had a hunger for human flesh.

Romero's inspiration came from Richard Matheson's 1954 book

I Am Legend. In the book a plague ravages the world,

turning those infected into vampires who attack the few remaining

individuals who are immune.

|

Bela

Lugosi as the Zombie Master in White Zombie.

|

I Am Legend had already been made into

a film, The Last Man on Earth, in 1964. (Later it would

be committed to celluloid again in 1971 as The Omega Man

with Charlton Heston and then again in 2007 as I Am Legend

with Will Smith). Since the idea of vampires had already been

taken, Romero needed to come up with his own monsters for the

movie. Instead of drinking blood, he decided to have them consume

flesh. He never referred to these resurrected monsters as zombies,

but used the term ghouls.

In fact, the roots of Romero's ghouls go back

not to Vodou, but probably owe more to writer H.P. Lovecraft

and his short story Herbert West - Reanimator. Lovecraft's

tale has a mad scientist who, like Frankenstein before him,

spends his time reanimating dead bodies. These critters, though,

have a taste for human flesh and the good doctor gets disemboweled

in the end by his cannibalistic creations.

In June of 1967 a handful of movie makers, led

by the then 27-year-old Romero, descended onto the small town

of Evans City, Pennsylvania, some 30 miles north of Pittsburgh,

to film the picture. The grainy, black and white, low-budget

production was originally called Night of the Flesh Eaters.

However, a last minute conflict with another film with a similar

title forced it to be released as Night of the Living Dead.

Romero's plot had a group of people trapped in

a farmhouse while across the east coast of America, freshly

dead corpses start rising from the grave, then attacking and

consuming the living. The mood of the film is unflinchingly

grim as one by one the members of the group are picked off and

eaten or are turned into ghouls themselves (including an 11-year-old

girl that snacks on her father). In the end there is only one

survivor of the night's carnage and he is killed when he is

mistakenly identified as a ghoul himself by authorities.

From

Tasteless Junk to Historical Significance

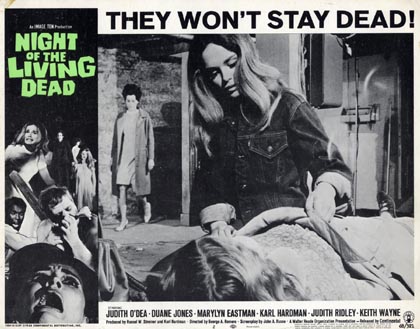

|

A

lobby card from Night of the Living Dead.

|

When it came out in 1968, the movie was heavily

criticized because of its explicit content. Variety labeled

Night of the Living Dead an "unrelieved orgy of sadism."

Even those that liked the film, such as critic Roger Ebert,

found the way it was often shown at Saturday afternoon matinées

filled with children, irresponsible. "I don't think the younger

kids really knew what hit them," Ebert said. "They were used

to going to movies, sure, and they'd seen some horror movies

before, sure, but this was something else."

Audiences ate it up, however, and eventually the

film was recognized by the Library of Congress as a film deemed

"culturally, historically or aesthetically significant." The

New York Times, whose critic had originally referred to

it as a "junk movie," later put the film on their list of the

Best 1000 Movies Ever. It spawned dozens of look-alikes

and Romero went on to do several sequels himself.

Its reputation grew as film analysts read deeper

meanings into the movie's prevalent slaughter. The little girl

eating her dad became a symbol of the breakdown of the patriarchal

nuclear family. Others found the movie a "grotesque echo of

the conflict then raging in Vietnam." Hints about America's

racial tensions were also found in the motion picture because

the sheriff that callously shoots the lone survivor is white

and the victim black.

The original film, which cost only $114,000, earned

$18 million internationally and might have made even more. Unfortunately

the distribution company, in changing the title at the last

minute, accidentally removed the copyright notification. Under

the law at the time this put the film immediately into the public

domain.

Zombies

as a Symbol

|

The

zombies are coming! The zombies are coming! From Night

of the Living Dead

|

The number of zombie films that followed Night

of the Living Dead are legion. Some are deadly serious,

like Romero's squeal, Dawn of the Dead (1978), though

many have a streak of humor, as in Zombieland (2009),

or are outright comedies like Shaun of the Dead (2004).

The zombie craze has infected filmmakers and audiences throughout

the world as Japan's Stacy: Attack of the Schoolgirl Zombies

(2001) and Cuba's Juan of the Dead (2012) testify.

Whatever the type of film they appear in it is

clear that these new flesh-eating ghouls have joined vampires

and werewolves in the modern myth of the paranormal. Why is

this new type of zombie so popular, when its predecessor, the

traditional zombie of Vodou only showed up in a handful of films

between 1933 and 1969?

Some people have suggested that zombies represent

the trials we face in modern life. Max Brooks, author of The

Zombie Survival Guide, writes, "You can't shoot the financial

meltdown in the head -- you can do that with a zombie... All

the other problems are too big. As much as Al Gore tries, you

can't picture global warming. You can't picture the meltdown

of our financial institutions. But you can picture a slouching

zombie coming down the street."

Like the invading aliens of the 50's once symbolized

the communist menace and vampires stood in for the AIDs threat

of the 80's and 90's, modern zombies are emblems of our contemporary

anxieties. Unlike others, though, these dangers arise close

to home due to our recent economic misfortunes. As Adam Baker

writes in the Huffington Post. "Zombies are us. Our friends,

neighbors and relatives. They are not a threat arrived from

overseas or outer space. They are our own communities turned

monstrous and hostile, folks we pass in the street recast as

deadly predators. Nightmare imagery of desolate streets, cannibal

hoards, barricaded homes under relentless assault, is our everyday

word viewed through the lens of economic desperation."

|

Actress

Kelli Maroney gets grabbed by a zombified cop in 1984's

Night of the Comet.

|

As with past crises, these films will hopefully

help us cope with these stressful times. In this age of social

upheaval - high unemployment and underwater mortgages - we look

to tales of survival to comfort us. If the kids in Night

of the Comet (1984) can outlast a zombie apocalypse and

the end of civilization, perhaps we can survive the real estate

implosion and our vanishing IRAs.

Copyright

2012 Lee Krystek. All Rights Reserved.